Stories about the simplest, everyday things are the most charming. This short piece by Uche Akumbu is such a lovable read. It all begins with a nice family dinner, but then things quickly go downhill. Enjoy!

I don’t know how it was at your house but at ours, breakfast was always a frenzied affair. School was at the other end of town, and the only way to beat the go-slow was to leave the house at about quarter past six, which often meant that we had only about five minutes to gulp down bread-and-butter and tea or cornflakes as fast as we could without staining our school uniforms.

Dinner, in contrast, was such a formal affair that we sometimes begged to be allowed to eat in the kitchen like we did in the afternoons, three of us seated on low stools, catching eba straight from the aluminium container it had been made in, kneading the soft sticky mass into balls before dipping them in our shared bowl of soup. The big wooden mortar, turned upside down, served as our centre table. To pre-empt any fighting, Aunty Rosemary would wait for us to finish eating before spooning out individual portions of meat.

“Only bush people eat that way.” Mummy was bent on turning us into ladies.

On account of her being Mummy’s cousin’s half-sister’s illegitimate child, we never really considered Aunty Rosemary as a member of the family, so while she often ate her dinner in the Boys Quarter, the remaining five of us ate ours at the dining table. Well, six actually, if you counted when Granny was still living with us.

Daddy may have sat at the head of the table but it was Mummy who presided over our evening meals, never failing to check our palms and nails for ink marks and dirt before we sat down to eat; keeping track of who prayed the last time and ensuring that we maintained proper etiquette throughout the evening meal. The slightest deviation from her prescribed do’s and don’ts prompted a discreet “Ahem”, which could mean anything from “Get your elbows off the table” to “Stop slurping”.

On this particular day – and I remember it well because we were having moi-moi for dinner. We loved loved all things beans but moi-moi especially because Mummy was quite inventive with the fillings and you never knew what you were going to get in yours, half an egg, chunks of corned beef, giant shrimp, or our least favorite, spring onions; usually served with akamu on the side, or with custard, for us kids.

As I was saying, we were all eating, and then Granny cleared her throat. We turned to hear what it was, this time.

“This food is too oily.”

That said, she concentrated on extricating the boiled egg from the rest of the meal. The fork-and-knife rule did not apply to Granny.

“Chidi” Mummy turned to her left, “Granny thinks our food is too oily, how about you, do you agree?”

Daddy chewed for about five minutes. “Well…” He paused to take a long drink of water before continuing his verdict. “A little.”

“A little”, Mummy repeated, eyebrows raised. “A little.”

Now, there are two things my mother does not joke with – her cooking and her sewing. Most weekdays, she closed up her tailoring shop 4pm on the dot, not just to leave Aunty Rosemary free to go to evening school, but to do most of the cooking herself; so you can imagine how she must have felt.

Perhaps if Daddy had not been so preoccupied pouring milk into his bowl, he might have noticed that Mummy’s jaw was set, her eyes narrowed and her lips pursed to the extent that the bottom one had all but disappeared.

I had only seen that look on her face twice. Once, when she spied Aunty Rosemary helping herself to the tin of cream crackers normally reserved for visitors and then, the first but last time I stole money (I think it was twenty naira or so) from her purse. I can’t speak for Aunty Rosemary but as for me, I have since suppressed all memory of the beating that followed.

“Mama, I have respected you enough but now, let me say this once, and let me say it clearly; if all you are capable of is nitpicking my food day in day out, maybe you shouldn’t be eating it; in fact, maybe you shouldn’t even be staying in my house.”

All this was rendered in a cool, flat tone, sans eye contact.

Granny’s response was delivered in mime. She got up from her seat and clutched her chest tightly as though she were having an asthma attack. Apart from the wheezing, the only other sound that she could muster, over and over again was “Ha!”

“Okwuchi!” Daddy banged his fist on the table.

“Okwuchi, what?” Mummy fired back. “All she does is to insult me day in, day out and yet you keep on acting deaf and dumb. I’m fed up, Chidi, I’m fed up.”

But by then, his retreating figure was shuffling down the corridor. “Mama, wait….”

He hadn’t even bothered to excuse himself.

Beside me, Nonny, normally so fidgety, sat paralyzed; Chisom’s face now resembled the congealed pap Daddy had abandoned but her eyes had yet to match Mummy’s apollo-like redness. Save for the spluttering of the generator coming from outside the window, it was unsettlingly quiet. I reached for a second helping.

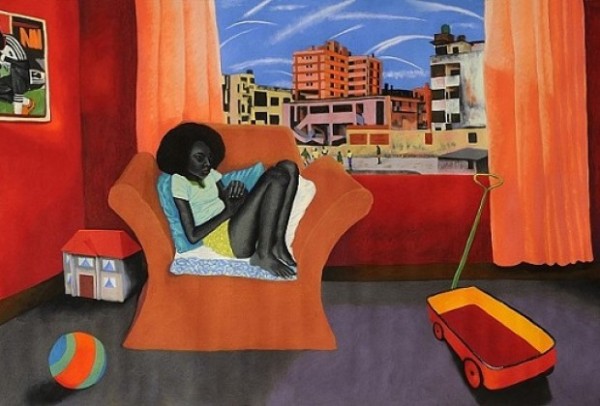

Image by Mthethwa. See more of Mthethwa’s work HERE.

***

Akumbu Uche was born in Kaduna, raised in Port Harcourt and educated at the University of Jos. Her writing has appeared in The Kalahari Review, Saraba Magazine, Qarrtsiluni and elsewhere. She lives in Lagos.

Akumbu Uche was born in Kaduna, raised in Port Harcourt and educated at the University of Jos. Her writing has appeared in The Kalahari Review, Saraba Magazine, Qarrtsiluni and elsewhere. She lives in Lagos.

mariam sule February 04, 2015 15:05

Such details. I enjoyed every bit of this. So beautifully written