Clemantine Wamariya and her sister left home to escape genocide in Rwanda. They wandered from refugee camp to refugee camp for 6 years until they gained asylum in the United States where they now live.

Clemantine, who does advocacy work against genocide, recently shared a longer version of this story in the online magazine Matter. [Read Here] It’s a moving tale about the search for survival in the face of senseless violence.

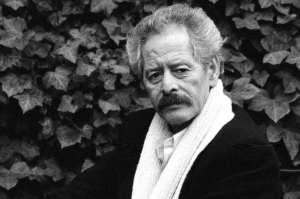

In the course of making sense of the violence she witnessed and experienced, Clemantine says that she turned to the writings of the British German novelist, W. G. Sebald. She read and reread his major works: On the Natural History of Destruction, Ring of Saturn, Austerlitz, Vertigo, and, Emigrants. Sebald gave her insight in her attempt to think through the violence she witnessed. “Sebald,” she writes, “offered a method, a technique for navigating out of the fog.”

When I read that, I immediately racked my brain to see if there were any African authors who could have offered Clemantine the kind of solace or clarity that Sebald did. Teju Cole perhaps? Or maybe Ivan Vladislavic? Or even Wopko Jensma? I had in mind works that made the act and form of storytelling bear the burden of suffering and violence in a way that left room for reflection. The point is not to look for African versions of Sebald but to ask what is different in the way Sebald writes about violence and the way someone like Uwem Akpan does in Say You are One of Them.

In his collection of stories, Akpan stages scenes after scenes of suffering in different African settings—Rwanda, Benin, Kenya, Nigeria, and Ethiopia. The stories are known for their gut-wrenching grit. Some of the scenes are particularly difficult to read because they show children living in degrading circumstances. Akpan is a fine writer. And perhaps there is some ethical value in painstakingly documenting the dark, uncomfortable details of these fictional lives. I don’t mean to single out Akpan’s work, but there is a general sense that his collection of stories is the poster child of African poverty porn.

Sebald’s writing are deeply invested in thinking about the relationship between history and violence. The Holocaust, as he saw it, is an event that endlessly reverberates through history. It is not just a moment in time that we lose sight off in the fog of history but a living past that continues to haunt our present. Violent moments in history—there is a long list of them: slavery, King Leopold’s Congo, the decimation of the native Americans, etc—leave ghostly residues that haunt the present of our everyday lives. What is so remarkable about Sebald’s writing is his ability to convey stories about violence with richly evocative imagery. His writings are mournful and deeply resonant and stunningly beautiful.

The difference between this kind of writing and the so-called poverty porn is the difference between evoking violence for the sake of genuine reflection versus putting violence on display as a scene for the reader who is, first and foremost, a voyeur. Poverty porn invites the reader to a theatrical display of violence in which the humanity of the narrative subject is sometimes put in question.

As a voyeur, the reader wants more and more of the scenes of suffering because it feeds a perverse pleasure to see human life reduced to shocking levels of depravity. I’ve heard the objection that poverty porn enlightens the reader by keeping things real, that it shows us the truth about violence without all the filter. Those of us who study fiction know that depicting violence in horrifying levels of vividness does not make it any more real.

But there is an even greater danger as Conrad’s Heart of Darkness makes only too clear. People try to convince us that Conrad’s heart was in the right place. Apologists have gone hoarse trying to make the case that his representation of the Congo as some kind of purgatorial underworld was a way of creating awareness about the evils of Belgian colonialism. Be that as it may, Conrad did not have to deprave the bodies of Africans to show their suffering. Whether or not you agree with Achebe that Conrad is racist, you must, at least, see that there is something obscene about his portrayal of Africa and the injustices done against her. The obscenity is what many African readers find hurtful not Conrad’s intentions. There is a way to show suffering that isn’t at the cost of dehumanizing the victimized.

The Sebaldian way of writing about suffering keeps a respectful and meditative distance from the scenes of violence it addresses. And in that gap or, rather, chasm that exists between the reader and the scene of violence, he erects this febrile space crowded with ghosts where readers are invited to enter at the risk of being implicated in the violence of history.

Writers who write about violence should think deeply about what they want to achieve. Fictionalizing violence should not be about simply re-enacting scenes of violence for people to see. It should be about revealing the logic of violence, how it works, etc. Isn’t there an ethical obligation to do right by those who suffered? Can we not find ways to represent their suffering without subjecting their bodies to all manner of indecency?

Writings about violence should captivate us in a way that allows space for us to think, for us to feel implicated, judged, unnerved, and vulnerable. Stories about violence should serve as a summoning of the dead and not the exposure of their bodies in the stark finality of suffering.

************

Post image via African Digital Arts

Peep this: The Perils of Poverty Porn | intunewiththeinfinite August 24, 2015 11:13

[…] the article ” On fictionalizing Violence: Sebald Versus Poverty Porn” by Duke Ph.D prospect Ainehi Edoro, the writer looks at how different writers have used violence to […]