Except at the end of the cycle, when the AFRO PRESIDENTS pub fills to capacity, Jomo always stops by for a drink. Today he occupies a spot close to the pub’s Eastern portal. His eyes are glued to a book. Reaching out for his beer-mug, he raises it above his grey beard and takes a long, noisy swig, his craggy face lighting up with satisfaction. For the umpteenth time, he pushes his reading-glasses up the bridge of his nose. Maybe, he should get one of those popular, Sight-Enhancing-Implants, everyone has opted for. Despite efforts to dissuade him, he has hung on to his reading glasses. The monotony, here on the Transit-zone, has him reading more and more. From the corner of his eyes he sees Mwalimu float in.

“May the tail-end of this cycle conclude without incident,” he greets Mwalimu, his eyes quickly shifting back to his reading.

“And all other portions of the coming cycles,” Mwalimu greets back, craning his neck to see what he is reading.

“I thought that book was critical of you?”

“I thought so too, and that’s why I never read it until now,” Jomo says. “Wish I had read it earlier. The man makes a good point.”

“Too late in the day to be saying that, don’t you think?” Mwalimu says, floating even closer.

Jomo slowly places his book face down and contemplates Mwalimu, who is gently stroking his moustache with his fore-finger.

“You won’t believe who I met, in the open space, where those opposition characters like to hang out. I don’t usually go there, but today I missed the peak hour cloud-shuttle and when the next one swooped in, it had a faulty guiding-system. Not about to wait for another, I risked floating across the short cut and came face to face with Jaramogi. The man still wears that ridiculous hat, and Akala-shoes. For a moment I thought he would stick out his thumb and shout ‘Dume’.”

“And so you went and looked for his book? ‘

“No! He gave me a copy. It’s an interesting read, this – NOT YET UHURU. You should read it”.

“I already did on earth”.

“Oops! I forget, back on earth, the two of you had a shared ideology.”

“If a lack of rapaciousness is what you mean, then I’m guilty as charged.”

“No! I meant that shenzi, Eastern-experiment you insisted on propagating. So much bull…, if you ask me. It left everyone impoverished.”

“Your own son ‘Uhuru’ is looking east, now.”

“Don’t be deceived by that China-nonsense. The muzungus were damn right when they said—‘a fruit never falls too far from the tree.’ The boy is just surviving. As for your people, they have finally seen the light and are looking westward. ”

The two remain quiet for a while. In the distance the Transit-point, crier can be heard. In a dolorous tone, he reels out the names of those that are to be dispatched to Omega. No one knows what awaits one in Omega. But if the crier’s anguished tone is to go by it cannot be pleasant. A hush envelopes the pub.

“I’ve never really understood the formulae they use to calculate the period of stay here on the Transit-Zone, before one is ripe for dispatch,” Jomo says.

“Neither do I, but I’m not about to take on the crier, over it.”

“Better the Desert you know, to the promise of an oasis.”

“People like Kwame and you, have been here tortoise-years,” Mwalimu says. Jomo is about to respond, when Kwame floats in.

“Ah! The East Africans are at it again; fraternizing with none other than their own,” Kwame, says extending out a hand to Mwalimu. His hair is parted on the side, and he wears a radiant smile.

“Talk of the devil…” Mwalimu says, rising to hug him. Jomo gestures a greeting with his eyes and returns to his reading. Not waiting for invitation, Kwame settles between the two and summons a waiter, with a flick of his finger.

“A double,” he says, not even glancing up at the young waiter in a spotless white tunic.

“How is our Redeemer doing?” Mwalimu asks, in a teasing tone.

“No better than our Ujamaa-architect,” Kwame says. “You know, the damn thing could have worked, if only you had allowed it time and not forcibly transferred people to those ridiculous, collective farms, like Stalin did.”

“And how would you know? You were long called, when it was going on.”

“Word gets around.”

“At least I got it off the ground. One cannot say the same for you.”

“And what is it engrosses the Burning-Spear so?” Kwame says, his focus shifting to Jomo.

“A book,” Jomo says, not bothering to lift his eyes from his reading. He considers Kwame pretentious and his flaunted urbane-mien, phony. He may not agree with Mwalimu’s frugal and self-effacing ways, but the man is real. The same can’t be said of Kwame.

“Of course I can see it’s a book. What book is it that has you undivided attention?”

“Trust me you wouldn’t like it.”

“I once read your – FACING MOUNT KENYA. Found it a bit parochial.”

“And what would your majesty decree, I write about?” Jomo says, his red eyes straying from his book. “A rumbling political treatise, I suppose?”

Mwalimu lets loose a shrill laugh.

“The man at the extreme end sends his greetings, ‘Osyegafo’,” the young waiter says, pointing to a man at the bar. Kwame turns to see Milton, hunched over his drink. He waves out his greetings and Milton waves back.

“Some of the stuff you poke fun at was what set the pace for political activity in Africa. We were Pan-Africanists, while you were still cooling your heels in jail,” Kwame says, his attention back on Jomo.

“Seek ye the political kingdom, and all else shall follow,” Jomo mimics. “Quite poetic, I must say, but not true. Some of us sought the economic kingdom, and all else was added unto us,” he says, laughing.

“Mwalimu here never sought the economic kingdom, as you put it. Yet the cohesion and stability he achieved for his country was remarkable. We don’t hear of ethnic cleansing where he came from. We can’t say the same for your country, can we?”

“Why don’t you speak for Ghana?”

“It isn’t doing too badly. Why do you think Obama opted for Accra on his first African trip when he had the choice of overrated Nairobi, the city of his father.”

“Forget about that confused Luomerican. Soon enough he’ll realize, home is home,” Jomo says. He has now abandoned his reading, and his gold-gilded glasses dangle on the bridge of his nose.

“I’m tired of this halfway-house nonsense. When do we get to leave for Omega?” Mwalimu says to diffuse the tension.

“It is never wise to wish for what you do not know,” Kwame says. He is about to continue when an air of excitement suddenly electrifies the pub, and the presidents drinking in the neighboring clouds suddenly rise. All eyes are on a lean grey-haired man, in a flower patterned shirt.

“Amandla!” the man shouts in a shrill voice, his age-spotted face lighting up in an infectious smile. Everyone cheers. He floats up to where Samora is and the effusiveness of their greetings has Jomo and Mwalimu smiling.

“They certainly have had something in common,” Kwame says a glint of mischief in his eyes.

“Was this Madiba man for real? Which sane man relinquishes power after only one term? Its’ scandalous and unheard of in Africa,” Jomo says.

“True leaders do not wait to be bundled out or to die in power. But how would any of you – life-presidents – know?” Mwalimu says.

“Oh! Yes. We’ve heard it before, how Senghor, Amadou and your good self, voluntarily quit. What you forget is, this Madiba guy did only one term. But again, look at the mess his so called Rainbow Nation is in and the ANC’s waning popularity. They are even lynching Africans now. The man should have hung on a little longer,” Kwame says.

“That is the only reasonable thing you have said this cycle,” Jomo says. “And to think we were blamed for not actively supporting their struggle. So much, for the so called—Front Line States”.

“Look at Pierre in tiny Burundi, using every trick in the book to hang on. Who do you think he takes his lessons from? This terrible, extension-of-term addiction of leaders will be Africa’s un-doing. Uganda has normalized it and Rwanda, quickly caught on. As for senile-Bob— clawing his way into a century and still dying his hair jet black—the less said, the better. The fools continue to commit atrocities against their people and the toothless, talk shop— the AU–continues to watch, helplessly. The only time they seem to unite is when one of them is threatened with prosecution. I would never have stood by and watched such nonsense in my time. That’s why I kicked out Amin.”

“And replaced him with Milton,” Jomo says, his tone heavy with sarcasm.

“You are one to speak. Had you not been called, you would be one of those clingers-on. Who doesn’t know? You did more sleeping than ruling during your last years with all sorts of shadowy characters calling the shots,” Mwalimu quips, causing Jomo to bristle.

Two Persuaders, in their customary orange tunics float in, and there is a sudden hush. One of them floats up to Madiba, and bows. “May the cycle bear peace, Zanta,” he says.

“And only peace, Anta,” Madiba responds. “Why two persuaders, Anta?” he asks.

“There are those that are yet to unlearn the violence of earth. For them persuasion can only be by way of superior force,” the persuader says.

“Peace.”

“Peace, Zanta.”

The two persuaders quickly float out, their orange robes fluttering, as they exit through the Pub’s Southern portal.

“Now you see how humility wins you respect even in this forsaken, Transit-Zone? It’s the first time I’ve heard the thuggish Persuaders refer to anyone as ‘Zanta.’ This Madiba guy is certainly something,” Mwalimu says.

“It’s not humility, far from it. The man’s spirit is broken. All those years in Prison could not have left him normal,” Kwame says.

“The man is an icon. Had we all lived by his creed, Africa would be a better place,” Mwalimu says, but Kwame is no longer listening. His eyes are glued on three men who have stepped in through the West-Portal. The bespectacled one has a white gown, the second, a showy, green agbada with a matching hat and the last a well fitting army uniform and beret. The uniformed man has incision marks cutting across his un-smiling face. He walks over to the edge of the bar and settles there. The other two stand by the portal, deep in conversation.

Kwame quickly floats up to the two and receives a warm hug from the man in white. They exchange a few pleasantries, before the two newcomers re-engage in their earlier talk. Feeling left out, Kwame floats back to Jomo and Mwalimu.

“And who might those two West Africans be? One of them looks familiar,” Jomo says.

“Stop pretending you don’t know Zik. The man was the first president of Nigeria, just about the time you were Prime Minister,” Kwame says.

“Oh yes! Your Igbo mentor. The guy who just like you got kicked out through a coup?”

“You can’t even begin to hold a candle to Azikiwe. The man was a true nationalist.”

“If memory serves me right, the guy supported Biafra and only made an about turn when he realized the thing couldn’t fly.”

“Zik was always a nationalist,” Kwame says, his voice rising, a notch higher.

“Weren’t we all, when it suited us?” Jomo says.

“No! Some of us were Nationalists to the very end,” Mwalimu says. “Building a Nation is like a marathon. There are no quick fixes or shortcuts. Everything you see going on down there in Africa reflects our actions as leaders, and there is no escaping from it. And by the way, when you were called, did they allow you carry all that wealth you amassed? Look at miserable Sese Seko, in that ridiculous Leopard-skin hat, all alone, in his usual corner.”

They all turn to watch the frail-looking, somber-faced, bespectacled, Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga.

“Compare him to Madiba, over there, happy and smiling. One had mansions in Paris, Brussels, Geneva and every other western capital and tons of money pilfered from his people. The other had nothing. Yet when the later was called, the airspace over his country was filled with jets as leaders of all races, religion and every political persuasion flocked in to pay their last respects. As for the former, all the wealth he plundered could do no more than buy him a tiny burial patch, in a cemetery, in arid Rabat, far away from his people.”

For a long time, after Mwalimu stops speaking, all the three founding fathers remain silent, each lost in his thoughts.

***********

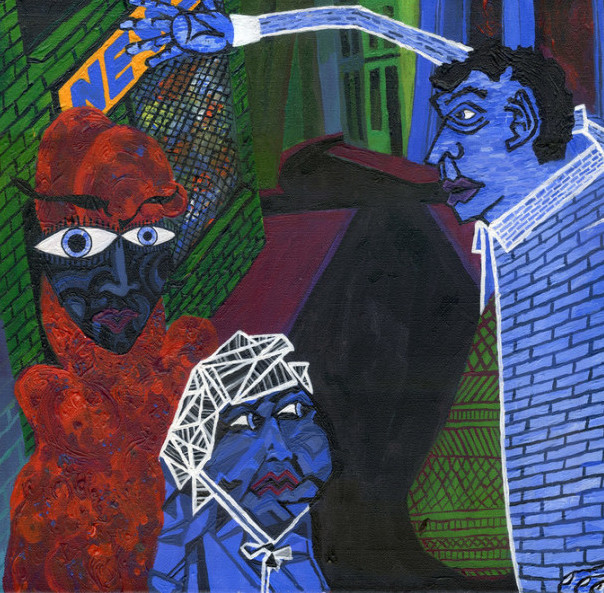

Post image by Chris Murtagh via Flickr

About the Author:

The writer practices law in the lakeside town of Kisumu, where he lives with his lovely wife and two sons. He has been published in the Munyori Journal and was short listed for the 2010 Golden baobab writing prize.

The writer practices law in the lakeside town of Kisumu, where he lives with his lovely wife and two sons. He has been published in the Munyori Journal and was short listed for the 2010 Golden baobab writing prize.

.

Morris Odhiambo July 19, 2023 04:43

Thanks for sharing. A very creative piece and the characterisation is just perfect. Congratulations.