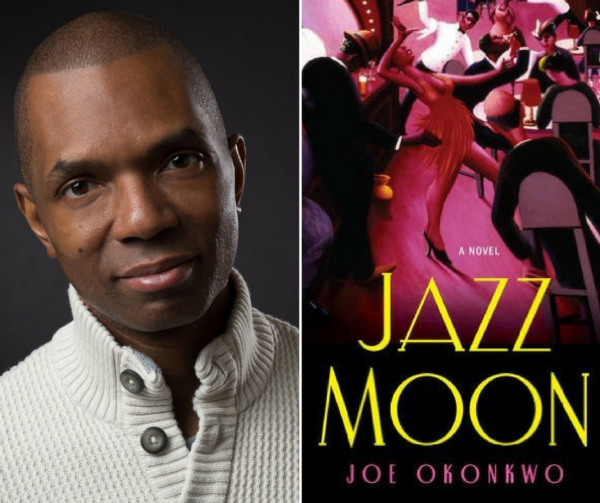

Joe Okonkwo’s debut novel, Jazz Moon, came out in June of this year. Described by David Ebershoff, author of The Danish Girl, as “passionate, alive, and original,” it follows a gay male poet’s journey in the 1920s from the American South to Harlem and then to Paris, handling complexities of character when impacted by art and love and race during the Jazz Age. His writing has been compared to those of Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes and James Baldwin and Richard Wright.

Okonkwo, who is Prose Editor at Newtown Literary, will also be Series Editor of the 2017 Best Gay Stories anthology, an annual publication by Lethe Press. A 2015 Pushcart Prize nominee for his Storychord story, “Cleo,” he has an MFA in Creative Writing from City College of New York and is represented by the Baldi Literary Agency.

Last month, he granted us an interview. Read below.

***

We’re honored to have you with us, Joe. Congratulations on having your debut novel out. How did Jazz Moon come about?

Thank you! It started as a short story back in 2004. I heard about a short story contest in which the word limit was 1,500 words. I had wanted to write a gay Harlem Renaissance story for some time and I thought, “Oh sure, I can write this story in 1500 words.” Well, twelve years and 93,000 words later, the novel is here.

Jazz Moon takes us back to the 1920s, nearly one hundred years ago; through Harlem and the American South and Paris, and into the life of a married gay man as well as the race relations that define that era. It’s quite a range. Could you tell us about the research you did for the novel?

I read lots of books. I read books about the Harlem Renaissance and the people who powered it and its cultural and political impact. I researched jazz and the jazz stars of that era as well as other black entertainers. I read about blacks in Paris and the racism they faced, which was very different from the kind of racism that blacks in the United States were facing. Blacks in the U.S. dealt with segregation and violence and a denial of voting rights, whereas in Paris blacks were welcomed with open arms and fetishized as exotic celebrities. I read about the ocean liners of the era and the clothes and cars and the visual arts. I read everything I could to get a feel for the period, so I could bring it to life for the reader as vibrantly as possible.

There’s an interesting scene in the opening chapter where your protagonist, Ben, is asked if he has anything published and he mentions two works of his and, suddenly, his wife Angeline twitches her lips, and then goes on to announce that “Mr Johnston’s a busy cat. He don’t want to hear about your poetry, even though I know he’d love it.” I laughed reading that. Is that you poking fun at a writer’s vanity?

Not quite. Ben’s wife has a very specific reason for not wanting Ben to talk about his poetry at that moment. But I don’t want to spoil it for those who haven’t yet read the book.

Ben’s marriage to Angeline is their mutual escape from their past. And then his eventual affair with Baby Back Johnston falls short of his expectations as Johnston prioritizes his music over their relationship. His life seems trapped in a circle of need and disappointment. Could you let us in on his character’s development?

Jazz Moon is very much about the search for self-worth, self-love, self-value. It’s a personal and creative odyssey, which is a journey so many of us—particularly artists—engage in constantly. Ben begins by depending on other people—his lovers—to provide him with self-worth, but he starts to learn to depend on—and love—himself.

You have passages of Ben’s poetry inserted into Jazz Moon, interspersed with the narration, much like A.S. Byatt does in Possession. Could you tell us more about that?

One of my early reviews criticized the inclusion of so much poetry in the novel. The reviewer said it disrupted the flow of the story and suggested I ditch the poetry or write a book of poems next time. I couldn’t disagree more. Ben is a poet, so it makes sense to include his poetry. Rather than disrupting the flow, I would argue that the poems contribute to the story by providing insight into Ben’s emotions, reactions, behavior, and desires. The poetry also amplifies his development (both emotional and creative) over the course of the novel.

David Ebershoff further describes Jazz Moon as “a moving story of traveling far to find oneself,” and, in your interview with Newtown Literary, you talked about having lived in “a multitude of places,” and now you refer to “a personal and creative odyssey.” I want to ask if there is an aspect of your life’s journey that shaped your novel. Have you even ever needed to undertake that journey of self-discovery?

I knew I was gay when I was thirteen. And that was difficult. Today, thirteen-year-old gay boys and girls in the United States can be encouraged by the progress made with gay rights and same-sex marriage. They can see openly gay politicians and celebrities and positive portrayals of gays on TV and in movies. But when I was thirteen, we had the advent of the AIDS crisis, which set the cause of gay rights back at least a generation. I didn’t want to be gay. It took a while to accept myself. Jazz Moon’s protagonist grapples with his sexuality. His struggle is not based on my own, but I certainly drew on that struggle when writing the book. And I used to identify as a poet primarily, so that certainly found its way into the story. And my own struggle with self-worth helped to shape Ben, although he is not based on my life. As far as undertaking a journey of self-discovery: I do that with every single story I write.

Let’s talk about your influences. Your book is being situated in the tradition of Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes and F. Scott Fitzgerald, all anchors of the literary jazz movement. Your style has also earned comparisons to Richard Wright and James Baldwin and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and you have stated somewhere how influenced you are by Toni Morrison and Shakespeare. What do you draw from these writers? And who else is important to you?

The first thing I look at when reading a book is the writer’s style and craftsmanship. I look at how they use language. I look at how they shape the narrator’s voice. And I look at how they use that style and voice to move the story forward because great style doesn’t mean a thing if it isn’t used effectively to tell the story. Writers like Shakespeare, Morrison, Baldwin, and Hughes know how to both explode and finesse language and use it to create compelling stories. Other writers who have influenced me: Thomas Hardy, Mary Shelley, Gloria Naylor, Alice Hoffman, Andrew Sean Greer. I’m currently reading Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. It’s an amazing book; I’ve never read anything like it. It’s a serious political book with flashes of absurdism and even farce. And I recently read Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, which just won the National Book Award and may also have changed my life.

The literary scene was recently lit by another debut novel immersed in jazz, Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s Tram 83. And with Jazz Moon now, we’re being moved to really pay attention to that music form. What is it about jazz music that inspires and draws you in? To what extent does music—its structure, its movements—offer literary possibilities?

Jazz is distinctly American. More than that, it’s distinctly African-American. It’s one of African-America’s most important contributions to world culture. I love the history behind it. And I adore the sound of it! It can be playful or sorrowful or bluesy or sexy. As far as jazz’s literary possibilities: One of my goals with Jazz Moon was to capture jazz’s musicality—the playfulness, the sexiness, the blues—particularly in the many sections that take place in jazz clubs. I want the reader to actually hear the music, the rhythms, the cadences. Obviously, I’m not the first writer to do this. Langston Hughes essentially invented the jazz poem with his first published collection, The Weary Blues, in 1926. Toni Morrison also uses jazz rhythms to great effect in her appropriately-titled novel Jazz, which also takes place during the Harlem Renaissance.

Jazz Moon grew out of a short story, and you have some stories out there, one of which, “Cleo,” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Considering that the literary climate has always favored novels over short stories, would you write a collection of stories if the opportunity presented itself?

Sure. But I think I’m more likely to create a collection of my previously-published stories rather than set out to write a collection from scratch.

Let’s discuss the Best Gay Stories anthology you’re editing, to be published by Lethe Press. Could you tell us about it?

It’s an annual anthology of stories featuring gay male protagonists. All of the stories have been published previously in various places during the preceding year. Lethe is one of the more prominent gay presses in the U.S. I published a story called “Skin” in the 2015 edition. I’m really excited to take the editor’s helm. I can’t wait to delve in and discover other gay worlds. So often people talk about “gay culture” or “the gay experience” as if all gays experience the exact same things (this also happens a lot in regard to “the black experience.”) Of course there are similarities and a good deal of common ground, but everyone’s gay experience is different. None of them are identical. So I’m really looking forward to seeing the many stories that writers will submit and diving in and getting a glimpse of the rich diversity of the gay experience.

Thanks Joe for taking the time out to chat with us.

*********

Post images via Joe Okonkwo.

John Adewoye December 17, 2016 08:07

My first fasination is the author's last name, Okonwo. It is a name with Nigerian origin. A country dark in confusion and no vision for the present or future generations of lgbti within her; yet outside her, names like Okonkwo glow in glory because environment have come to appreciate lgbti people. I am also impressed and very curious about the juxtaposition of poetry and prose in the book. That is an idea I have nursed and will work on writing the story of my life. I need to lay my hands on the book. Congratulations for the job well done Joe.