In the morning, there is an urgent knocking on my door. I wake up with a start, stare into the darkness for a second, and check the time.

5 a.m.

Annoyed, I drag my feet and open it to see my father beckoning me outside. “It’s not even 6 o’clock yet—,” I start, scratching my boxer-clad thighs and clutching my shirt in one hand.

“Shut up and come and see.”

I follow him outside to the wall beside the veranda. My mother and my sister are standing there too looking at me fearfully from underneath their hairnets. “Look,” my father points.

Looking, I see nothing. “Eh?”

“Young man, I say, look!” He points again. I squint and look harder. There is a peculiar oblong hole in the wall. I straighten abruptly. “When—”

“Today,” my mother says, “Gifty saw it when she woke up to sweep the compound.”

We are silent. I know what they are all thinking. What does the hole mean? Electricity tapping or the inevitable visit of the armed robbers? Since the increase in power cuts, holes like these have become more common in middle class generator-owning households like ours. Young jobless men, usually from within the community, target houses which have an almost ceaseless power supply. Over a few weeks, they find their way into the house somehow and drill a hole a little at a time into which they would insert a small Chinese invention locally known as ‘get-get.’

No one is sure how get-get works. Somehow it siphons electricity from one household into another one, tricking the thief’s electricity meter into thinking it is receiving power from the local ECG. Recently, a scarier trend has emerged. It appears that get-get houses are being visited by groups of armed robbers. People speculate that it happens when the thieves notice the household uses copious amounts of the electricity that is so scarce in these times. The armed robbers do not care who they shoot in the course of their spree. Obviously, we know waiting to be robbed is probably a bad idea.

My father calls the police that morning. Naturally, they refuse to come without their usual ‘insurance fee.’ Unfortunately, my father considers himself an upstanding citizen, a nonbeliever in corruption and bribery of any kind. After threatening to expose them “to all the media houses!” he slams the phone angrily and turns to us. “We’ll catch them ourselves,” he says dramatically.

So there we are. It’s 2:15 a.m. and our family is sitting on the veranda in the dark, dressed in our jogging clothes. I’m clutching a homemade cricket bat, my sister and my mother are holding butcher knives in both hands, and my father is slowly rotating the old farmer’s gun, trying to calm his excited breathing.

We hear a sound and stiffen.

Tap, tap.

Someone is walking barefoot towards us. My father switches on his flashlight and says “Hei stop!” There’s a young man standing there in dirty red shorts and a basketball jersey. He’s frozen in fear. In his hand is the incriminating evidence: two small chisels and the tell-tale silver gleam of a get-get. “Is there anyone with you?” my mother asks. The man shakes his head, no. My father approaches him with the gun cocked and seems satisfied when a thin stream of urine runs down the man’s leg.

“What is your name?”

“Paul sah.”

The man looks at the gun and falls to his knees with his arms raised. “I beg don’t kill me sah.”

“Come,” my father says, grabbing the man’s arm and dragging him towards the house. My mother follows, shiny knives aimed at his back. My sister and I look at each other with bemusement. My parents believe that a good talking to will dissuade any delinquent from walking the path to destruction. I am positive that in an hour or so the young man would wish he had been taken to the police station instead.

When I enter the living room half an hour later Paul is sitting on a low stool with his head in his hands.

“I wan’ go school but no money! No money!” He looks up. I can see a lone tear roll down his dark sweaty face. My father rises slowly from our large brown couch and walks over to his briefcase that is perched against the centre-table. He pulls out his chequebook. I have a feeling he rehearsed this move. Writing out a cheque he passes it to the man.

“Take this and go back to school. Education will take you anywhere!”

My mother nods in solemn agreement.

“If we see you here again you won’t be this lucky,” my father adds.

Paul stands, holding the cheque gingerly. “Thank you Sah! God bless you Sah!” he salutes, his voice breaking.

I walk out of the living room as my parents usher him out. I don’t want to stick around for my father’s follow-up speech on how my own education is preventing me from becoming a good Ghanaian citizen. I fall asleep just as the power goes out.

A few months later I’m sitting with my parents observing them with boredom as they argue over a television program on good governance and corruption. I casually mention that I saw Paul walking around our neighbourhood.

“Oh really?” my father’s face brightens. “How is he?” Without waiting for my reply he starts to talk about how everyone can be saved with the power of school and a scolding. My mother, his loyal supporter, nods wildly in agreement, occasionally saying, “That’s right!” and “It’s true!”

“So,” my father asks after he has run out of steam, “How is he?”

I pause. The ‘area boys’ told me that Paul used my father’s cheque to buy an expensive assault rifle. Impressed by the caliber of his weapon, he was quickly invited to join a group of local robbers. I saw him as I was taking the lonely back route home at dawn after sneaking out to go drinking.

He was with a group of men who talked excitedly amongst themselves, waving their guns without fear.

When he saw me, he stopped and saluted. I had those moments when a person evaluates all their life actions. Paul turned to his friends and said, “This is the boy. His father gave me the money.” The other men laughed and clapped me on the back. With each clap I felt myself age. “Don’t worry eh,” Paul said to me, “Tell your father that his house is safe. I told everyone he paid me.” I could do little but nod.

Satisfied, he moved on with his friends.

“My boy,” my father says again, “I said, how is he?”

I smile. “He’s okay. Said he started school again. He says to thank you for your contribution.”

There’s a happy silence as my father sits back in his brown armchair. “I told you,” he says. My mother adjusts her hairnet and nods in agreement. The power goes out. He sighs happily. I do the same. We both feel safe, though for different reasons.

After a few minutes my mother stands up and announces she is going to bed. I walk to the garage to turn on the generator and make a mental note to cover up Paul’s get-get hole in the morning.

**************

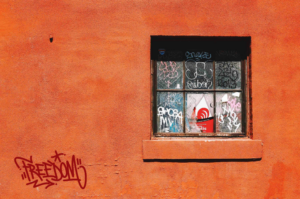

Post image by AK Rockefeller via Flickr

About the Author:

Elfreda Tetteh is a 24 year old Ghanaian living in Toronto and is a recent graduate of Carleton University. She spends her time navigating the world of adulthood and hitting brick walls.

Elfreda Tetteh is a 24 year old Ghanaian living in Toronto and is a recent graduate of Carleton University. She spends her time navigating the world of adulthood and hitting brick walls.

Gwen S. September 21, 2017 08:46

Great story! Loved the ending!