Adichie is in love with Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s artwork. We are 100 percent here for this kind of artistic affection, especially when it brings into focus the work of two leading figures of Africa’s literary and art worlds.

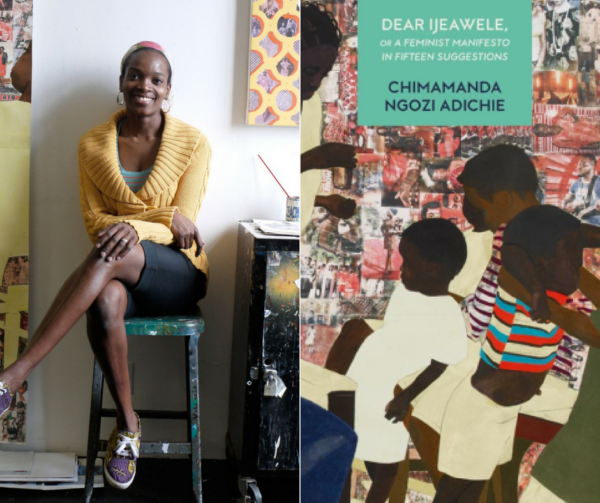

You might recall that last year, Adichie’s Facebook post on raising a girl child went viral. You might also know that the post is getting a second life as a chapbook. The book, titled Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions, comes out March 7.

For the art work on the cover of the UK edition, Adichie used one of Akunyili-Crosby’s artwork. A few days go, Adichie shared the cover on Facebook and gushed about her admiration for the artist’s work. “Akunyili-Crosby’s work,” she writes, “is quite simply beautiful.”

In the post, she talks about what she finds remarkable about Akunyili-Crosby’s work in general and also what drew her to that particular artwork, titled 5 Umezebi Street, New Haven, Enugu, 2012, used on the UK book cover.

She writes: “It filled me with nostalgia, a sweetly-sad nostalgia that brought into focus childhood memories of faded Sunday afternoons, slow and somnolent, lunch of rice and stew after church, visitors dropping by, my mother’s George wrapper hanging outside in the backyard, and the feeling that even the butterflies had paused. The week’s dissembling had been laid to rest, leaving only a fleeting human purity.”

The entire post is a loving tribute from one artist to another. We highly recommend it.

Enjoy reading!

On Njideka Akunyili Crosby

Dora Akunyili once thrust a rosary into my hand.

“Keep it with you at all times to protect you, because success brings envy,” she said, and added, as though to brook no argument, “It was blessed in Rome.”

A slate-colored rosary with a shiny crucifix. I have kept it since, part comforting superstition and part tribute to a woman who was one of the best public servants Nigeria has ever had.

As the director-general of NAFDAC, the food and drug regulating agency, she fought the importers of fake medicines and the makers of unsafe foods, unnerving business interests that had long been complacent in their corruption. They went after her, and she survived assassination attempts; a bullet once narrowly missed her head, striking her ichafu. She was radical because she had integrity in a system that was unfamiliar with integrity. A businessman once told me that Dora Akunyili was the only public official he respected. “She smiles with you but she will insist that you do the right thing,” he said.

She was kind and vigorous, and when she spoke, she widened eyes as though to better convey the force of her conviction.

Nigeria lost one of its best when she died three years ago of cancer.

It’s a little too predictable to say that her spirit lives on in her daughter, the artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Perhaps it does. But Akunyili Crosby has claimed an aesthetic that is wholly hers.

The first time I saw her work, I was instantly taken with its tone, which seemed to me emotionally true, both nostalgic and celebratory, both old and new. Here was multimedia as both cultural commentary and cultural memory.

There was the bold romance of her metafiction – the inserting of herself and her husband in scenes of Igbo life, ubiquitous celebratory images, lovely and loving, and insistent. We will be seen. We are here. She is wonderfully subversive, even if she doesn’t mean to be, because she is asserting the the multiplicity of selves often denied artists whose work is steeped in place – that she is a product of a particular Igbo world, and that she shares her life with a man far removed from that world, and that both of these realities co-exist and are normal.

In ‘5 Umezebi Street, New Haven, Enugu, 2012,’ she uses mundane details as entry into the sacred act of preserving memory. The dining table at the back with its milo and flask and Nido, breakfast accoutrements on permanent display. The bathroom slippers. The guests drinking coke. The dutiful but sharp-tongued-behind-the-scenes househelp or cousin from the village with her isi owu. The child’s protruding navel. The contentment. A slice of middle-class Igbo life – before the proliferation of mobile phones.

It filled me with nostalgia, a sweetly-sad nostalgia that brought into focus childhood memories of faded Sunday afternoons, slow and somnolent, lunch of rice and stew after church, visitors dropping by, my mother’s George wrapper hanging outside in the backyard, and the feeling that even the butterflies had paused. The week’s dissembling had been laid to rest, leaving only a fleeting human purity.

Akunyili-Crosby’s work is quite simply beautiful. Its visual energy is like highlife music, filled with a slow wisdom. Its layering is a statement against static, against mere surfaces. It breathes.

I like to think of DEAR IJEAWELE as universal and rooted in its Igbo provenance, as a wide look from an intimate standpoint, and as ultimately hopeful. I’m so pleased that the British cover is this beautiful piece of art, which could very well be described in similar words.

Hannah February 28, 2017 04:53

I love Akunyili-Crosby's work! I haven't read her bio, so knew nothing of her relationship with Dora. Wow. And Chimamanda slays with her descriptions as always.