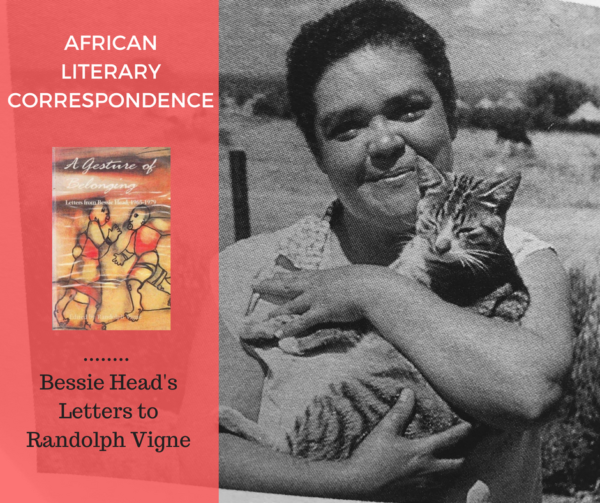

“Forgive the vanity, but few people equal my letter-writing ability!!” writes Bessie Head on March 14, 197o to her friend Randolphe Vigne. Head is not exaggerating. For the last few months, I have been reading many of her letters, and I find them to be such beautiful things. They are raw, honest, and loud, but there is enough humor and intellectual depth to give you the impression that you’re reading provocative think-pieces. Reading Head’s letters has had me thinking a lot about the status of letters in African literary culture.

Imagine getting a hold of letters exchanged between Chinua Achebe and Flora Nwapa, between Wole Soyinka and Derek Walcott, or those between Tutuola and the folks at Faber and Faber as they struggled to make sense of the mind-bending story that became The Palmwine Drinkard. These kinds of correspondences offer a window into the lives of writers who we’ve only known through the scripted versions of their public image. We get a glimpse into their personality, what inspired them, the challenges they faced, and the friendships that sustained them. Letters also provide behind-the-scene accounts of grand historical forces. They give us a private view of how great literary forms and movements came about and evolved.

Unfortunately, African literary correspondences are not widely available. Many of these documents are still under lock and key in private collections. Those that are open to the public are lodged in special collections in libraries scattered all over the world. Until they are collected, published, and made available to the common reader, we can as well consider them unavailable.

There are a few exceptions, but they are mostly in the South African literary side of things. Take Bessie Head, for example. Some of her letters have been collected and published. In fact, just last year, Jacana Press featured some of her letters in a volume that included letters by two other South African women.

The collection I’ve been reading is the 1991 volume titled A Gesture of Belonging: Letters from Bessie Head. The letters in the collection are those that Head shared with Randolph Vigne who is also the editor of the volume. Vigne is a close friend and confidante. She met him during her Cape Town years. The letters collected in this particular volume begins when Vigne is living in London. The letters span over a decade, from 1965 to 1979. At the time, Head was living in Serowe, Botswana as a political refugee and a single mother. The collection contains narratives and reflections that uncover the traumas, insecurities, and creative life of one of Africa’s celebrated writers.

The letters are, in part, an account of how Head came to be a writer of note. They take us back to the beginnings of her literary career, when she wrote mostly short stories, essays, and even dabbled into poetry. But they also show the hardship of the years leading up to the publication of When Rain Clouds Gather. She complains about living in a 12ft by 12ft room with her son and how at some point she comes close to being homeless. She makes references to being knee-deep in debt and having trouble feeding herself and her son. But somehow she found the inspiration to write. She could not afford a typewriter, so she composed her work by hand and often times by candlelight.

But writing brought her comfort. “When life is a dreadful pain and bleak,” she writes, “you sort of counter this with an opposite feeling. The day I wrote the short story about jackal-blanket maker was indeed a vile day.”

As late as April 1968, right before When Rain Cloud Gathers comes out, she is still living in grinding poverty.

Perhaps I cannot describe to you how I have lived this whole year. I have had to discipline myself to stay a week on end without food. And yet somehow hold my mind together. There have been days and days when I’ve had to give all the food to my son and then sit up the whole night typing my book…There is nothing like outright hunger over a prolonged period to make you lie back and stare deeply at life.

As the publication of the book draws closer, her tone is less strained and tortured. She revels in delight as positive reviews of the book are published out in the weeks leading up to the official release. The publication of the novel changed everything. Royalties began to come in. The letters from this period is delightful to read. They are filled with news about her new house.

I am building a small house, with two rooms, and a third divided into a bathroom, toilet, and kitchen. I am building it with the thousand pounds I received from the paperback sales of Rain Clouds to Bantam Books. The house is minute but the pride is overwhelming. It is the first brick thing I shall ever own…The house when complete will cost me about 600 to 700 pounds.”

It doesn’t come as a surprise when she decides to name the house after the book: “The thing is, the book and the house go together, and I would very much like to call the house Rain Clouds.”

The letters also give us access into the larger literary landscape. By 1970s, demand for African literature was increasingly based on its educational value. Head came under pressure to target her fiction at a younger, school-age demographic. She was a bit puzzled that Simon and Schuster “promoted Rain Clouds as a book for kids.” How can a novel so deeply layered with nuanced philosophical questions be targeted at kids? At first, she didn’t really care as long as it meant more money in her pocket. But she became a bit frustrated when Simon and Schuster asked her point-blank to write a teen novel modeled after The Catcher in the Rye. “I wrote back and said I don’t write for a particular audience…Why can’t they let me alone, just as a writer?”

Head struggled with mental health issues most of her life. Frequent bouts of depression were punctuated with time spent in the psychiatric ward. She talks about being arrested for going off in a “screaming rage” at someone. There are times when she had to take three “tranquilizer pills” a day to keep herself from acting violently towards her son. “It is as though I want to scream and scream everyday or just walk out and kill the first person I see, stone dead,” she laments.

Apparently, Head was often accused of husband-snatching, an accusation that she often laughed off by saying that she was not pretty. “I am a hell of an ugly woman – I don’t know why I’m in so much trouble,” she writes.

There are moments that deserves roaring laughter—like when she worries that her waistline was expanding in proportion to her age.

Last week I turned 33. A month before I gained control over the workings of a bicycle. The two goes together as far as my birthday is concerned because for some years my waistline was keeping pace with my age e.g. 30 years old – waistline 30; 31 years old – waistline 31; 32 years old – waistline 32. Bang went the order this year! Age 33 – waistline 31.5. It’s the bicycle. But more. There’s a blue sky over head and little pathways ad the wind in my hair. What a life! That’s why the lady is a tramp! (127)

A Gesture of Belonging is a treasure trove of moments, narratives, and ideas that throw light on one of Africa’s most enigmatic literary figures. If you delight in stories and escapades about the writing life, you will find in this volume pure perfection.

Mildred Barya May 01, 2017 10:26

I want this Letter book. What a delight!