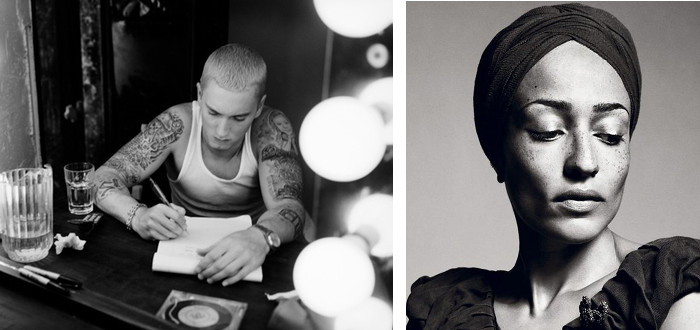

Let’s settle the bald facts: Eminem has secured his place in the rap pantheon. — Zadie Smith

Ever since British novelist, Zadie Smith, wrote the roaringly funny novel, White Teeth, she’s being a favorite among lovers of contemporary British fiction. Nothing’s more sexy than a novelista–pretty woman with crazy writing skillz. Ms. Smith has a new book out–which you should check out here–but back in 2003 she interviewed Eminem for Vibes Magazine and later wrote a piece, based on the interview, for the Daily Telegraph. In the essay, she says lots of interesting and provocative things about the contemporary culture of rap and Eminem as one of its dominant figures. What I have here are short excerpts from the piece. Enjoy. Hope your week starts out nicely. Oh, Hurricane Sandy is not playing, so stay safe folks.

“As Chris Rock had it, something sure has changed in America when the best golfer is black and the best rapper, white. Rock’s choice of word is remarkable: not richest, not most famous, but best. Because there can be no doubt about it any more – it’s become churlish to deny it. You may dislike his language, his philosophy (and it is philosophy) or his hair dye. You may say it can’t last, and unusually, for a rapper, he will agree with you (“I’m gonna do the music as long as I feel it, but the truth is that I can’t rap forever”).

But let’s settle the bald facts: Eminem has secured his place in the rap pantheon. Tupac, Biggie and Pun are gone, and right now there just isn’t anyone else but Eminem who can rhyme 14 syllables a line, spin a tale, write a speech, subvert a whole genre, get metaphorical, allegorical, political, comical and deeply personal – all in the one groove of vinyl. Eminem is a word technician. He makes words work for him, he’s never lazy. Most rappers can be branded: we play Snoop for that down-and-dirty feeling; when you want to nod your head and pop your collar, there’s Dre. Nelly will give you the songs of sex, Mos Def makes you want to start a revolution and Busta Rhymes is purely for bouncing to. Eminem, like Tupac before him, does a little of all these things. Like Pac, he does them with the integrity of an artist. This doesn’t mean that he is above the vulgar business of entertainment. Only that elements of these two rappers are, in the sacred terminology of rap music, kept real. Tupac only sold himself so far, never entirely submitting to the demands of the pop market, never self-censoring.

Eminem’s music shares Tupac’s obsession with truthfully representing a group of disfranchised people: “I love that Tupac cared about his people, from his background, his generation; he cared what they thought – and anybody else, who didn’t understand him, could go to hell.”

That role, being the truth-telling prophet to a generation, is troublesome. Some truths are hard and self-destructive. Some are conflicting to the point of schizophrenia (Tupac wrote the feminist elegy Brenda Has a Baby and the abusive Wonder Why They Call You Bitch; Eminem wrote Just Don’t Give a F 1- 1- 1- and Rock Bottom, in which he clearly does.) These boys are both Mad at Cha and not mad. They Just Don’t Give a F 1- 1- 1- and they do. Certainly they have problems, but they are not criminals. They are rappers.”

“The fact that a man picks up a microphone,” says Eminem, urgently, “that’s it, you see? That’s what makes him a rapper. It’s not a gun. It’s a microphone.” But this confusion of terms is at the heart of America’s love/hate relationship with rap music. In a 20-minute video montage that opens Eminem’s Anger Management Tour, a surreality takes over as we watch the most senior politicians in America, one after the other, stand up in the senate with a sheaf of paper in their hands, awkwardly reading out random lyrics, furiously condemning the dangerous social phenomenon that is Eminem. Even with the extra workload created by the War On Terror, it seems there’s always time left over for that old favourite, the War On Rap.

Before this kind of misplaced hysteria, good rappers do not back down. They defend the right to use words as any novelist or filmmaker is free to do. But the trouble lies deep within the form itself. Rap uses a narrative medium that mixes story-telling with dramatic monologue, boasting with political mission-statements, original poetry with endless quotation.

Of course, Eminem’s music is entirely self-conscious, it is about rap. It asks: just how mighty is the pen? Eminem talks the talk (Don’t think I won’t go there/ Go to Beirut and do a show there!), but he has never seemed truly interested in walking the walk. To keep it real within the logic of rap and rock means taking on the weight of the world you represent. Tupac, like Kurt Cobain, was never able to rid himself of the fatal idea that he should fulfil, to the letter, the life and death of the less fortunate people he represented. Eminem has turned from that idea, as his hero Dr Dre did.

“I had a wake-up call with my almost going to jail and s***, like, slow down. It wasn’t me trying to portray a certain image or live up to anything, that was me letting my anger get the best of me, which I’ve done many times. No more.”

******************

9 years later…

In an interview with Harper’s Magazine early this year, Ms. Smith looks back and reflects on meeting Eminem.

INTERVIEWER: “Do you have thoughts on Eminem the rapper?”

ZADIE SMITH: I interviewed him once and back then I had a lot of thoughts on him, but I think they may have faded—with my age, not his. The thing which struck me about him then, which maybe it’s a silly—again, it’s a very simple thought. But when I met him I felt that he gave me a poster. It was a big poster with all the history of rap, and he was there, and he was one of I guess four white guys, him and the Beastie Boys. So he was coming at that tradition from the outside and I thought I was coming at my tradition from the outside. And it struck me that if you are coming inside-out that way, that you have to work twice as hard. My mum always used to say to me, and I think a lot of black mothers perhaps say to their daughters, “Whatever you do, you’ve got to do it twice as well.” She was always telling me this. And I was always struck with Eminem that technically, when he was a young rapper, he was doing it twice as well. You might not like the backing music, you might not like the content of the songs, but in terms of the actual syntax, what he was doing in a line, he was doing it twice as well. He had had to prove that he could do this thing, because it was so easy to say, “Who the hell are you, you’re just a white boy from Detroit, who cares?” So he had to do fifteen times the amount of work, and that’s what attracted me to him as a rapper, because it seemed to me a real act of will on his part. He just decided he was going to be a great rapper, studied it, sat around with it, repeated lines over and over and over, completely obsessively, and finally achieved it. And I found that moving, I suppose. There you go, that’s my thoughts on Eminem.

Feature Image Via

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions