By Matthew Omelsky

Has African science fiction only recently come into existence? Or are we only now beginning to pay attention to it? These questions are complicated for a few reasons. For one, there is an extensive history of speculative fiction by white South African writers, arguably going as far back as Ferdinand Berthoud’s 1924 story “The Man who Banished himself.” But there has also been a repackaging of sorts of African SF in the last decade, with writers like Nigeria’s Nnedi Okorafor and South Africa’s Lauren Beukes entering the (somewhat) mainstream of both contemporary African fiction and speculative fiction. The path-breaking anthology AfroSF draws on both the strength of South African SF and this recent surge of internationally-lauded SF writers, bringing a sense of burgeoning cohesion to a genre that has until now largely been relegated to the periphery of African cultural production.

AfroSF is diverse and sprawling – its contributors hail from all over sub-Saharan Africa, and the contributions cover an astonishing range, from horror to erotica, cyberpunk to space exploration. What brings these varied stories together is the question of new forms of life on a radically altered continent. Some of the stories suggest a remixing of imperialist geopolitics, specifically a China-dominated Africa, such as Biram Mboob’s “The Rare Earth” in which Mandarin is spoken and the Yuan is used on the shores of Lake Tanganyika. Others, like Uko Bendi Udo’s “The foreigner” and Nick Wood’s “Azania,” present an other-worldy horizon of intergalactic exploration and terraformed planets pioneered by Africans. And some, like Rafeeat Aliyu’s “Ofe!” and Clifton Gachagua’s “To Gaze at the Sun,” rework the Scifi tropes of the cyborg and the automaton, making them feel almost organic to African spaces.

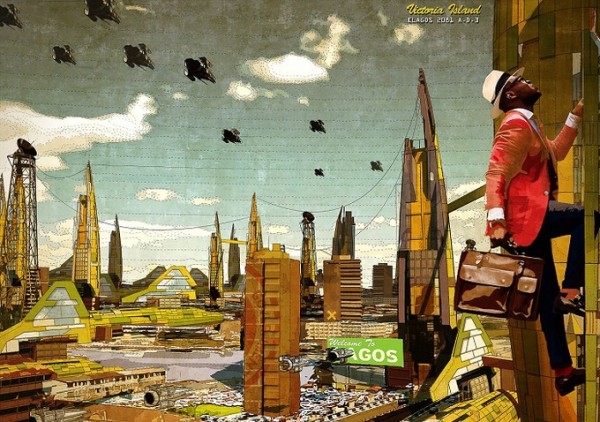

Perhaps the most pronounced current throughout the anthology is the question of a dying, contaminated earth. In these stories, lakes are rancidly polluted, forests have been stripped, and soils lay barren and charred under the sweltering sun. Two of the most evocative and beautifully composed contributions offer vivid illustrations of a withering planet. Nnedi Okorafor opens the collection with “Moom!” about a swordfish who defends her territory in the sea, continually spearing other invasive “creatures from the land” who bleed sweet black ooze, leaving their poison on the water’s surface. The swordfish undergoes a freakish Kafkaesque metamorphosis – she grows triple her size, forming spikes, hardened skin, and blackened eyes. The story closes by revealing that the creature this swordfish has battled is a leaking oil tanker sitting in the waters off the coast of Nigeria. In a different take on a disfigured earth, Efe Okogu’s “Proposition 23” is set in a snow-covered 23rd century Lagos, the most populous and polluted city in the world. Inside the city, humans live with the aid of an electro-neurological device that warms the body in the city’s everlasting nuclear winter and numbs the senses to the putrefied world beyond the city limits. Many of the writers in AfroSF leap forward in time to reveal the possible consequences on the African continent of our enduring neglect of the earth’s ecosystems.

Some of the contributions to AfroSF are also striking in how they reshape established conceptions of African cultural thought. The most salient example is Chiagozie Fred Nwonwu’s “Masquerade Stories.” The story revolves around the participation of several teenaged boys in a manhood initiation ceremony in the forest. The initial predictability of the narrator’s account of this rite is disrupted by futurist technology, namely ocular and auditory implants that heighten one’s vision and hearing to superhuman capacities. When one of the boys realizes that his ocular implants have recorded the dancing masquerades at the ceremony, a small group of them returns home to watch it on a Starwars-like holoprojector. The boys are astonished to see that one of the masquerades did not emerge from the hut along with the other masquerades, but had “shimmered into being,” possibly from the moving spec of light they could see hovering in the background. They are convinced that this masquerade, with its curved teeth, bizarrely placed arms, and the glowing device in its hand, is not human. “Could it be,” the narrator considers, “that this is actually an alien and my ancestors encountered them and thought them to be spirits…. Somehow, that did not sound strange to me.”

Nwonwu’s story recasts the figures of the spirit and the masquerade present in countless cultures throughout the continent. He reframes notions of ancestrality, and asks if perhaps the African – the human, even – might have some intimate relation to the unearthly. For him, the history of the continent and its cultures is not stagnant; it is mutable, generative, and open to contingency. While Nwonwu’s story provides a fresh look at tropes of African tradition, it also seems to resemble the origin myth of the Dogon people of Mali and their figure of the Nommo. The Nommo, believed by the Dogon to be amphibious ancestral spirits, originally lived in the orbit of the star Sirius and flew to earth in a seed-vessel. For the Dogon and possibly the characters in “Masquerade Stories,” unearthly life begat life on earth.

Gesturing toward the Dogon of West Africa and their ancient myths of origin, Nwonwu’s story demonstrates that African science fiction is not at all new – that perhaps what we call science fiction is inherent to African storytelling and myth. That tropes of extraterrestrial life, cosmology, and space travel existed in Africa long before the work of H.G. Wells. AfroSF may be a window into an emerging African literary genre, but more importantly, it forces us to reimagine what we know and may not know about the histories, futures, and cultures of the continent.

Image via

Thanks to Matthew Omelsky for writing this illuminating piece. He is a graduate student in English at Duke University, where he works on African novels, science fiction, and experimental film.

Thanks to Matthew Omelsky for writing this illuminating piece. He is a graduate student in English at Duke University, where he works on African novels, science fiction, and experimental film.

Order AfroSF HERE.

African Scifi makes a comeback | Sci Fi Generation July 24, 2020 20:18

[…] http://brittlepaper.com/2013/06/african-science-fiction-comeback-review-afrosf-matt-omelsky/ […]