They bump into each other as she leaves the studio.

They bump into each other as she leaves the studio.

It’s only 10 a.m. but Maya is already drained from the news she was forced to give in a neutral tone and expression. All around her, production people are shouting in jubilation; hands up and faces alive, like caricatures of happiness, not living, breathing human beings. A few people are huddled up in small clusters discussing this new development, saying things like, ‘It can’t be sustained.’ ‘It won’t last.’ ‘In a year, we’ll be talking about how this was a mistake.’ One voice says, “The North and West will survive, but us? What do we have? In a year, we and those bloody Muslims will be suffering in poverty.”

The chaos of their voices registers as a single, overwhelming force cutting off her ability to reason, and all she wants is to get as far away from people as possible.

She tugs on the microphone wrapped around her back and pinned to the neckline of her navy blue top, unwinding it, calling out to the nearest production man in a striped shirt to ‘catch’ as she flings it at him. He misses and wags a finger at her like it’s her fault for being too much of a girl to throw it right.

She heads to the heavy, white door, pulls it open and goes barreling into him. The folder she’s carrying comes tumbling down in a pomp, parade and whoosh of white papers and a lone pen. She grapples to keep the bottle of water and notebook in her other hand from going along with them. Stable now, she stares down at the mess on the floor to silently accuse them of betraying her on a bad day. They stare back up at her innocently, pulling her down to pick them up. The man standing in front of her barely registers until he mumbles, “Sorry,” under his breath and bends to help her with them.

She glances at him as she collects the papers he’s gathered up. Brown shirt, black trousers, chocolate skin almost exactly the same tone as hers, van dyke to cover sunken cheeks, lanky without being thin, a scar cutting through his left eyebrow. He doesn’t look like a journalist. But then again, neither does she.

They straighten. Her first and then he follows. He says sorry again for bumping into her and she says thank you to him for helping her with her life. They exchange a short, conspiratorial smile and she moves on, set for the newsroom.

Later, she finds him again on the vast, marble-floored verandah leaning against a thick, off-white pillar, with a cigarette held carelessly in between his index and middle fingers. She moves through the throng of people, the air of joy still palpable and present, to wait next to him for a taxi.

“Happy independence day,” he says to her.

She glances at him. “Is it Independence day?” she asks. “It feels more like a Monday.”

“A sympathizer,” he says and takes a drag of the cigarette. “I was starting to think I was the only neutral party.”

“I’m sure there are a few million of us.”

He shakes his head at that. “The world we knew no longer exists. We are now new citizens, have a new name, new passports, for all intents and purposes, we’re new people. Not very many people will resist the urge to say that that’s either good or bad. We’re a rare breed.”

She smiles at that. “I’ll add that to my profile.”

“You should,” he says. “In an age of mindless doubles, you…”

“Maya,” she supplies.

“Maya,” he repeats. “Are a dying breed.”

She thinks of her mother who is hard core pro their new identity and her sister who is fervently against and herself squarely in the middle, refusing to pick a side.

“You have to pick one,” her sister had said. “This isn’t the time to be lukewarm.”

Now, she repeats his phrase, “Dying breed.”

He holds out a box of cigarettes in his hand to her. She shakes her head, declining quietly. He straightens and holds out his other hand for her to shake.

“I’m Luke.”

“Maya,” she says as she takes it.

“It’s a strange day to meet, Maya.”

She smiles. “Yes, Mondays can be that way.”

He agrees. “Yes, they can.”

***

He tells her he loves her as the somber news caster announces that a faction within their new State has declared its intention to form a separate country.

“I love you,” he says over the sound of the TV, but she, head on his lap, eyes fixed on the images of faction leader and his camp, is thinking ‘and so it begins’.

Maya has been anticipating this for the past three months since their independence. It’s sooner than she expected, but not surprising. The carving up had left their new State the poorest and hardest to manage of the four, and the people too greedy and impatient to accept anything less than everything.

She’s not looking forward to what comes next. The violence, the uprising, the dialogue followed by more dialogue. The faction looks weak and at this point she’s sure they’re hemorrhaging sufficient backing for their position, which means they probably won’t last long, but who knows what it will come after them? Or after those who come after them.

“I love you,” he says again, louder.

This time she hears him, freezes and reaches for the remote to mute the TV. She looks up at him, positive that she’d heard wrong and asks him to repeat himself.

“I’ve said it twice already. You’re going to have use your imagination from now on.”

She laughs and responds, sure now. “I love you too.”

The feeling, all encompassing, safe and warm like a blanket permanently draped over her shoulders, follows her around. She takes it into the shower, to meals with her mother and sister, to work as she reads out the news script, voice never faltering. She carries it around and pulls it out the moment things go a little wrong, a safety net designed to catch her lest she fall into the world unprotected.

The day she wakes up cold, the feeling gone, she cries. Then she goes into work and reads into the camera that the new faction has been dissolved and their little country is intact again. She finds him on that same day, in his house, with eyes glued to the TV watching the President assure the people of their safety.

As she takes a seat on the arm of the chair he’s sitting on, he takes his eyes away from the speech long enough to register her presence. She searches his familiar face, trying to recreate the feeling and launches herself into his lap when merely looking at him produces nothing. He increases the TV volume, letting it form a third person in the room, an intermediary between them that makes it slightly less uncomfortable.

They go through this scene day after day, falling in with each other and the TV, listening to the news, immersing themselves in it to distract themselves from each other. One week, she makes up a million transparent excuses to save herself from the discomfort, the next he does.

She chooses, instead, to focus on embracing the camera in front of her. On the night she reads to their world that a new, different faction has broken out, this time not with words but with cutlasses and guns, the feeling returns.

Afterwards, she packs up her bags and leaves work, but doesn’t head straight home. She stops a taxi and tells the driver where to take her. Once there, as she raises her hand to knock on the door, it’s pulled open. He stands aside to let her in. Her bag finds a place on the couch. They don’t speak, they don’t reach for the remote, they make their way quickly to the bedroom.

***

It’s a contest of whose voice can reach higher and eclipse the other’s. She’s screaming, waving her hands at him, calling him a worthless, worthless bastard. He shouts back at her, stationary and vibrating, calling her a selfish, selfish, prig.

She tells him that nothing he says makes any sense, that it has been a while since he has opened his mouth and anything of use has come out. He tells her he can mention the exact moment she last did something that wasn’t in some way beneficial to her. They’re both right, they know, which makes them scream louder at each other.

She gets the last word in the battle as he storms out. She says, “You know, if you drank less you’d probably be more than a mediocre reporter.”

She regrets the words before she says them, but they come out anyway, uncontrolled, untamable, and once they are out she refuses to be ashamed of them.

On her way home, there are billboards and posters plastered on walls showing the President and the faction leader shaking hands, with nifty slogans like ‘One country, One people’ and ‘Peace Reigns’ under it.

Peace reigns, she thinks. And wonders where her peace is in this new world.

It’s exactly a week later that a tape sporting the faction leader’s nasal voice calling the President a pompous prick trying to screw them out of all the good positions surfaces. The posters are transformed. Mustaches and sunglasses are drawn onto the faces of both men, hand guns are placed in the hands they aren’t using for shaking.

She’s staring at one of the posters, tracing the mustache lines with her eyes, when Luke calls to apologize. And she, who had sworn just yesterday that in every version of reality and in every life time they were over, finds herself falling in love with him all over again.

***

Maya approaches the situation with the detachment of a scientist.

She hangs the calendar mass produced to celebrate the one year anniversary of their country, on the wall in her room and begins to chart their trajectory.

In the 7th box under January she writes: ‘Birth’ for the moment after her birthday dinner where he slips a bronze toned ring onto her finger and asks her to marry him. She is so entranced by it, she briefly forgets the health and electricity crisis raging on all around them.

20th February: ‘Death toll goes up’ she writes to indicate the day the food shortage deaths rose by 4 percent. Under it, she writes ‘Plan wedding’ for the amount of time she, Luke and her mother spent pouring over mundane, yet exciting details of venue, dress, and guests.

15th March: ‘Borders’ for the borders from the South opening up and letting in the food. The entire news coverage for the next two days is about the end of the hunger. She also writes in small, small print, ‘Mother’ for her absolute refusal to apologise to his mother after she had called Maya fat during lunch and Maya had gotten up and left.

24th March: ‘Rain!’ for the skies opening up and people pouring out onto the streets to dance and play in the mud, holding up buckets to collect water, ending the drought that had dried up the land. ‘Phone’ she writes for the moment in the evening she hurled her phone at his head for telling her she could try to sound less patronizing when she was reading the news.

3rd April: ‘Strike’ for the health strike ending. And ‘AWOL’ she writes because she turned off her phone and buried herself under the blanket although she had had plans to meet Luke and his friends for dinner.

31st April: ‘Reintegration’ she writes because that is the day a confidential source leaked that their country and the South are in talks to integrate the two countries into one, stronger force. It is also the day she writes ‘Ring’, because while in the middle of reading the six o’ clock news she goes into anaphylactic shock and almost dies, suddenly allergic to the ring she’s been wearing for months. The doctors cut if off her swollen finger and it lies in two uneven pieces in a bed pan next to her.

***

They agree that this doesn’t change anything.

She tells him her hypothesis, anxious and nauseous all at once. She pulls out the calendar. Their lives are etched in blue ink, the country in red.

“But we’re neutral,” is all he says in response to it. “Neutral parties, teamless individuals.”

So she explains in detail how their lives sync up to the rise and fall of their little State; how when it rises, they fall and when it falls, they rise; how instead of being neutral they have become a part of it.

He goes through each entry asking questions, trying to poke holes into her theory, but it stands against his interrogation, and after he’s through he looks as though he is about to vomit on his carpet.

And then they agree that this doesn’t change anything. They decide that they are rational, logical beings capable of deciding what happens, or doesn’t happen in their lives and that they will decide.

‘I decide’ is what she tells herself as she checks the news feed first thing in the morning to know how she will approach her day. Whether or not she’ll search him out as soon as she gets to work merely to prove that the currency plummeting does not change how she feels.

It’s what he tells himself as he does the opposite, ignoring the feed as long as he can because he doesn’t want to know. He wants to walk up to her unbiased, not thinking that the growing talk about the integration with the South is what makes him want to tell her that her rendition of Etta Jones’ ‘At last’ is the singular, most infuriating thing in the world and he hates it as much as he hates her in red.

But their rational, logical natures are not enough on the 16th when both countries make it official that the integration is in the works. They don’t talk or attempt to see each other during the televised visit of the Southern President, instrumental if the integration is to go forward as planned. And when they come back together once the talks stall because both sides can’t reach mutually beneficial parameters of governance, they don’t speak about why it took so many months for them to have a good day.

Three months later, two years after their Independence, Maya watches the live coverage of the integration in the newsroom with the rest of her quiet, somber colleagues. Once again they have a new name, new passports, new everything.

As she turns away from the screen, she spots him standing at the back of the room holding a pen between his index and middle finger the way he holds his cigarettes. She walks to the back of the room, intending to reiterate that this doesn’t change anything, but once she stands in front of him she sees that it changes everything. They are no longer the dying breed.

She walks out of the door without saying a word.

****************

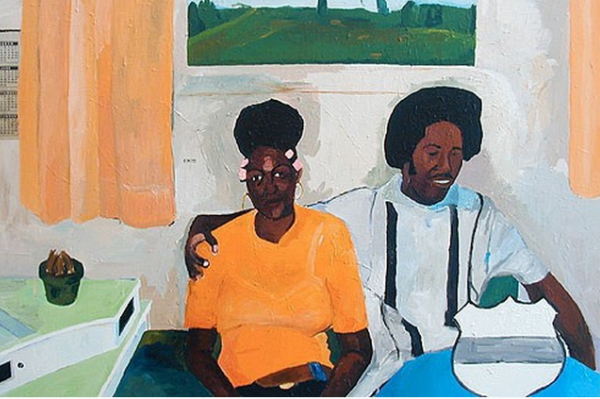

Post image titled Sis and Bra, 2004 by Henri Taylor via Manufactoriel

About the Author:

Zainab A. Omaki is a Nigerian by birth, Ghanaian by friendship and journalist by heart and profession. She lives and works in Abuja, Nigeria.

Zainab A. Omaki is a Nigerian by birth, Ghanaian by friendship and journalist by heart and profession. She lives and works in Abuja, Nigeria.

Ainehi Edoro September 10, 2015 16:07

Thanks Henry. That's such a lovely to put what's beautiful about the story.