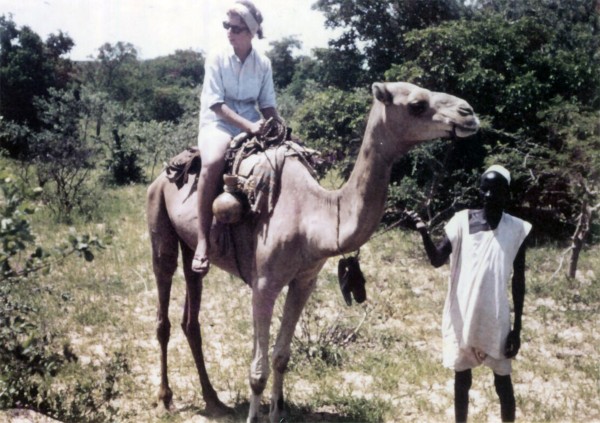

In 1962, Catherine arrived in Lagos as a Peace Corp volunteer. She was a bright-eyed young woman, recently graduated from university and eager to make a difference in the world. She’d studied German at the University and had been assigned to teach it to secondary school students in Nigeria. A couple of years later, she meets a young Igbo man named Clement Onyemelukwe, the chief engineer at the power holding company. From then on, their lives take a dramatic turn—they fall in love, get married, live through the Biafra War in a little Igbo village, and raise a beautiful family.

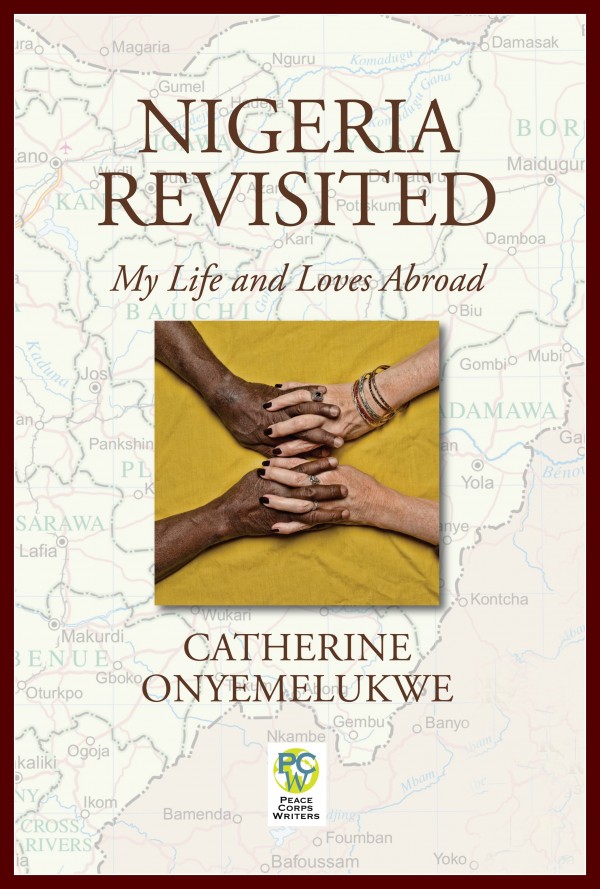

All of this and so much more is recorded in Nigeria Revisited. It’s a memoir, refreshing in its honesty but also endlessly entertaining. Abandon whatever assumptions you have of memoirs as stilted accounts of individuals with bloated sense of their self-importance. Nigeria Revisited

is a narrative packed full of intrigues and testimonies about how love can truly change lives.

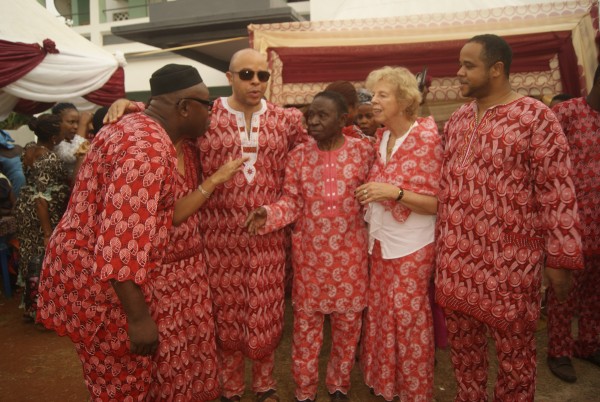

Onyemelukwe lived a life that transcended conventional ideas of who we should love and how we should love. And this love permeate the story, enlivens the truthful details she includes in the book—details that include everything from socialites of 1960s Lagos to the unimaginable difficulties of life in war-torn Biafra.

I am so delighted to bring you this interview with Ms. Onyemelukwe. In the interview she takes us through the process of documenting her story and transforming it into a beautiful memoir.

Enjoy!

***

What inspired you to write this remarkable story about your life in Nigeria?

Over the years when I have told people about my life in Nigeria, they often said, “You should write a book.” Gradually I began to take them seriously. I wanted people to understand the richness of the customs and sense of community that I found in Nigeria, and to have a window on a part of Africa that they wouldn’t see except through my story.

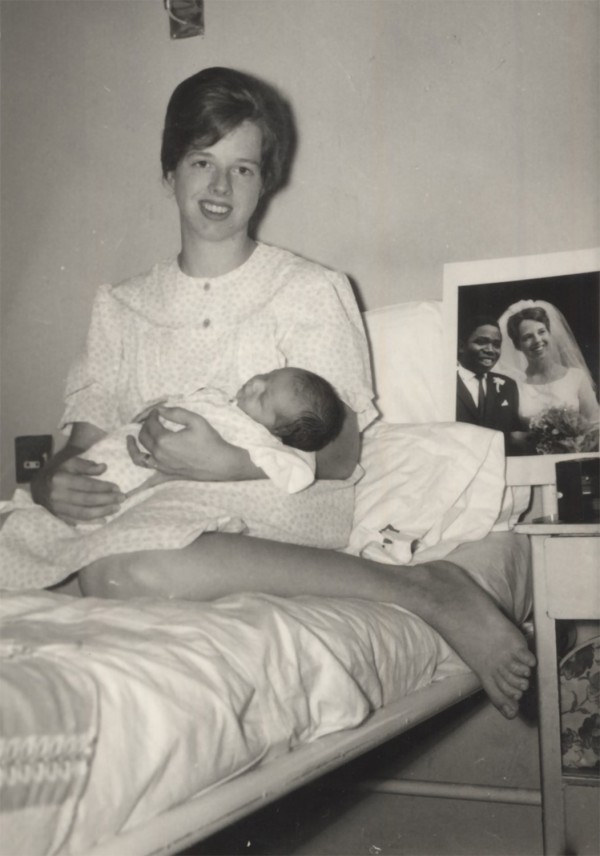

Your honesty is beyond refreshing. I found it inspiring—like when you take the reader through the travails of having your first baby in Lagos. What is the hardest part about telling your life’s story in an open and honest way?

Because I live my life looking on the positive side, I tended to report some of the most difficult experiences in a factual manner, without reflection. I didn’t want readers to feel sorry for me. Several times colleagues in my writing classes would tell me they couldn’t believe I wasn’t scared or miserable. So I had to imagine how I must have felt at the time, because I honestly didn’t remember the bad feelings.

I sat up all night reading the Biafra section. You talk about the pervasive feelings of mistrust that led up to the outbreak of the war. What was it like being caught up in all of that as an outsider?

Very strange. I was torn – part of me saying there was too much being made of Igbo fears, and part saying the Igbo massacres were real and threatening. I sensed the fear but didn’t feel it in my body. Clem and I were under intense pressure from my mother-in-law to flee Lagos. Finally I gave in to the surrounding belief that we were no longer safe in Lagos and owed allegiance to the East.

You could have gone back to the US. But you chose to stay, to go to Biafra and to contribute your bit to the political dream that was Biafra. Why?

I finally made the Igbo cause my own, since my husband and baby son were Igbo. I think I was also caught up in the excitement of creating a new country. Not only my husband but other Igbo people I had come to know gave me the sense that there was a possibility for Biafra to succeed.

I remember reading the Ahiara declaration a few years back and being inspired the Ojukwu’s vision and the clarity and passion with which he expressed it. What did you find more inspiring about the Biafra?

I was inspired by Ojukwu’s passion for the cause of an independent Biafra. He was a charismatic leader. He made me—and everyone—feel that an independent country of Biafra was not only possible, but just, right, and imminently realistic. I was inspired by my husband’s willingness to embrace the cause, and seeing the same willingness from others. And I think the idea of being part of the creation of a new country was inspiring too.

Not being able to afford a cake, you once stuck candles in a bowl of pounded yam to celebrate your son’s first year birthday. Why was it important to you to maintain a sense of the everyday in spite of the ruptures taking place in your lives during the war?

Just what you said – I needed to maintain a sense of normality, of everyday activities, in the midst of the war and its disruptions. I wanted my children to feel life was normal, and I wanted to feel it myself.

Has it ever occurred to you that Nigeria Revisited is a beautiful love story?

Thank you.

Why was it important to you share this aspect of your live with your readers?

I assume you don’t mean the love between my husband and me, but my affairs. I wrote about them without being sure I would include them in the memoir. My writing instructor and class members said just write; you can always take out what you don’t want to include. But as I wrote, and re-read and edited, I decided I really did want to include those parts of my life that were hidden at the time. I think having affairs changed me, made me more confident of my appeal as a woman, and gave me an understanding of human imperfection!

Let’s talk about the writing process. The book is filled with all these fascinating details. What did you do in preparation for writing? How long did it take you to finish the work?

I had given talks about Nigerian customs for several years, so I had the notes from those. I did a full book proposal with chapter outlines and sent it off to a publisher in late 2011. She rejected it, saying the story was fascinating but I needed to make it more readable. After that I started attending Westport Writers Workshop weekly classes for two and a half years, excluding summers. Every week I would read a segment of around 1000 words and have it critiqued by other class members and the instructor. Then I would revise and keep writing. I was able to read parts of most of the chapters during those months.

Nigeria Revisited reads like a novel. It’s drama-packed and gripping. What is the secret to telling one’s life’s experiences as a believable story?

Thank you! I learned technique in the memoir writing class – use dialogue to advance the story and reveal character, for example, and set scenes using as many senses as possible. I also learned to end each chapter with suspense wherever I could. After I’d finished writing, I hired the instructor as my editor, and she made a few more recommendations.

I imagine you’ve read Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun and other Biafra War novels. As someone who lived through the war, what do you think of these narrative adaptations of the war?

Yes, I’ve read Half of a Yellow Sun, but not other Biafra War novels. I think Adichie captured the war-time atmosphere very well. Her power of description – of people, actions, and scenes – is amazing. I have Achebe’s There Was a Country, but have just started it.

The Biafran dream many never have come true, but is there any way we can draw inspiration from what it represented?

The Biafran dream many never have come true, but is there any way we can draw inspiration from what it represented?

Yes, I can draw several lessons from Biafra. The Biafran dream taught us that even with very hard work and dedication one cannot always achieve one’s wishes. Sometimes there are too many factors outside one’s control.

Second, I think it taught me, or maybe reinforced for me, the importance of adaptability.

When I speak to audiences about my memoir, people often ask, “How did you manage to live in your husband’s village with no other white people, no electricity, no running water, no supermarkets?”

I had made the choice to stay, so there I was. Why not make the best of it? My primary focus was taking care of our children, and that would have been true wherever we were. So although the challenges of child-rearing were different, they still occupied my mind. In addition, I had the opportunity to learn Igbo, become closer to my husband’s family, and experience village life. I also learned that material goods are less important than safety and family.

Third, I would say that Biafra taught me that it is worthwhile to fight for one’s beliefs and be dedicated to a cause. Last, I think I learned how important commitment from many people can be in trying to make change. Sometimes just showing up is important—I think of this today when I support racial justice. I know that being a white ally and being visible can be effective at times in protesting racism.

******

All images provided by Catherine Onyemelukwe

Meet Catherine Onyemelukwe – The White Woman Who Married A Nigerian Man, Lived Through The War With Him and Made The Biafran Cause Her Own – Woman.NG February 03, 2016 09:45

[…] Edoro of Brittle Paper caught up with her recently. Here’s an excerpt from the […]