A couple of weeks ago, Zimbabwean author Petina Gappah announced on Facebook that she had some “glorious news” to share. The news was simultaneously delightful and shocking. It made her “squeal” and “shriek.” What was this momentous news? One of her stories was going to be published on the New Yorker.

This is an excerpt from the Facebook message:

Okay, now that it is all done, done, done, I can report the glorious news that I am to have a short story published in THE NEW YORKER !! I have been sitting on this news for a while. My agent first wrote me the news when I was in Zim. I squealed loads, and shrieked New Yorker, New Yorker, New Yorker, and my mum thought I was saying nyoka nyoka nyoka, snake snake, snake and she said kana motaura zvenyoka tinodzoka tovhunduka

You’re probably wondering: why would an established and award-winning author like Gappah freak out about having her work featured on the New Yorker?

The simple answer is that being published in the New Yorker is a big deal—bigger than most readers realize. The New Yorker is one of the world’s most coveted literary publications and many writers, including established authors, never get the chance to have their work featured in the magazine. Within the African literary community, only a handful of writers have the bragging rights of a New Yorker feature. As Gappah points out in the Facebook post, she is most likely the first Zimbabwean writer to be published in the Magazine’s 92-year existence.

She’s living the dream right now. We are truly proud of her and inspired by her all-round success as a writer.

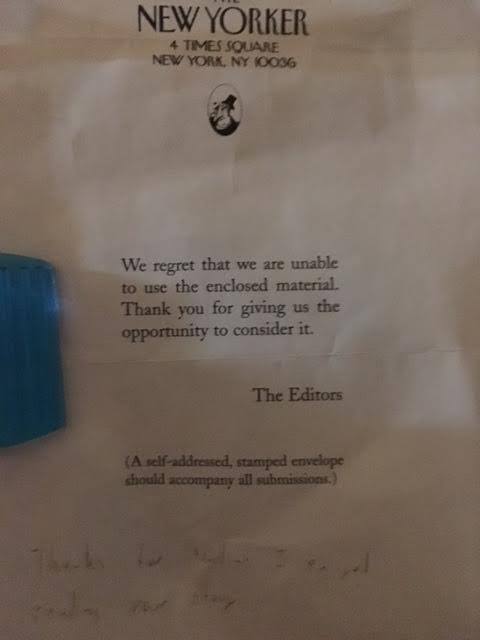

But her story presents a powerful object lesson that we thought needed highlighting given that we have a lot of aspiring writers among our readers. Gappah’s journey to the New Yorker isn’t as straight forward as you might imagine. In 2007, as Gappah recounts on Facebook, she submitted a story to the magazine. It was rejected. An official letter was, of course, sent to notify her of the rejection. Gappah shared the letter on Facebook, which we’ve posted below.

It reads like a typical rejection letter. It’s impersonal and has a disheartening tone of finality. But, if you look closely, you’d see that a handwritten note is scrawled at the bottom of page. It is faded and barely legible, but Gappah says in her Facebook note that it reads: “Thanks for sending. I enjoyed reading your story.” In spite of the rejection, the kind editor who read her work wanted her to know that there was something in her writing that was worth nurturing.

Instead of getting discouraged by the rejection, Gappah held on to the encouragement in the editor’s personal note. “It has been on my fridge since 2007,” Gappah reveals. This additional handwritten note, tacked on to the official rejection letter, became a source of inspiration for her. “I kept it as a talisman and took it as encouragement and vowed to work on my craft and submit again when I was better.”

Gappah would go on to publish a collection of short stories, An Elegy for Easterly, and a novel, The book of Memory, both of which are critically acclaimed. Her third book, a collection of short stories titled Rotten Rows is set for a UK release next month. She’s is also had the distinguished honor of being published on the New Yorker.

This is a beautiful lesson for aspiring writers. Not everyone would have the lovely editor who attaches a kind notes to a rejection letter. But we can all choose not to allow ourselves be discouraged by rejection letters and continue working hard at becoming the best writers we can be.

kemi May 02, 2017 05:53

Please how can i get The Book of Memory in Nigeria