Last year, we inaugurated the African Literary Person of the Year Award. The idea was to celebrate an African writer who inspired us in our lives as readers, fans, and critics of African writing and literary culture.

For those who are wondering, the selection is based neither on metrics nor on popular vote. I make the selection chiefly on the basis of my vantage point as the editor of a literary platform. My work at Brittle Paper situates me in the trenches of African literary production. It’s given me the ability to monitor trends in the global literary landscape. My presence on social media lets me see who is doing or saying what. One of the sobering aspects of my work is witnessing first hand the struggles — especially in worsening economic conditions — that aspiring African writers experience to nurture their craft. The award is subjective, but it is borne out of an intimate knowledge of curating various aspects of a global African literary culture.

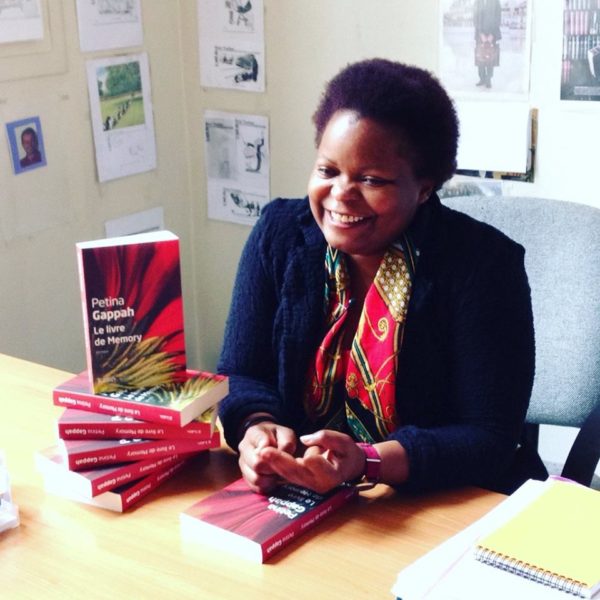

Last year, the award was given to Nnedi Okorafor for challenging reductive assumptions about what it meant to be an African writer and to tell African stories. Read about it here, if you missed it. This year, I celebrate a writer who has not only inspired us with her work, but also with her life as a writer. The 2016 Brittle Paper African Literary Person of the Year Award goes to Petina Gappah.

Gappah was born in Zambia, grew up in Zimbabwe, and has spent years schooling and working in Europe. She writes brilliant books. The Book of Memory is a beautiful book. It tells the story of a young woman whose life and body are caught in the clutches of that strange and beastly thing called the Law. In little over a year since The Book of Memory, Gappah released a new book. Rotten Row is a collection of short stories. Even in this collection, the law appears as the ghostly force shaping the lives of characters and their fate. Her engagement with the African legal archive through storytelling is truly remarkable particularly in the ways it opens up new aesthetic possibilities for African fiction.

Gappah is a hard-working writer. If you follow her Facebook updates closely, you might already know that she has a fourth book in the works. It is titled The Last Journey and takes us to an earlier time in Africa’s modern history. This kind of work ethic is worth celebrating. I am conscious of the fact that a good part of our readers here at Brittle Paper are aspiring writers. Thus, I’m always on the lookout for models that can inspire them and give them a realistic sense of what it takes to become a successful writer. Gappah’s experiences have been particularly useful in this regard.

She is open about her struggles as a writer. Not all writers are like that. There are some writers who build a deific aura around their craft. They give the impression that they have always been amazing and that they were essentially elected by the literary gods to pursue their craft.

Gappah is different. She doesn’t take her success for granted. When her story “A Short History of Zaka the Zulu” was published in The New Yorker, she posted the most humbling and inspiring celebratory message on Facebook. She opened up about being rejected by The New Yorker many years ago. She even shared a photograph of the rejection letter, which she says played no small role in setting her on the path to becoming a seasoned writer. This is the kind of honesty that inspires. It encourages the struggling writer to stay the course and put in the work.

Social media is still a mystifying invention. It is this place where most of us now live a part of our lives. We can’t say we fully understand it. But it brings us together. We form communities around things and ideas. Authors are fond of it for different reasons. There are those who use social media as a kind of pilgrim where fans congregate to offer some kind of worshipful honor. There are those who use social media as an announcement board and have little or no interaction with readers. Gappah’s Facebook page is an electrifying space for intellectual discourse. One day she is sharing prized legal advice on Zimbabwean book importation tax laws, the next she’s igniting spirited conversations about Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize win. There is no elitist posturing. She posts about her favorite Issey Miyake jacket with as much ease as she delves into a linguistic problematic in Shona language and literary archive.

Perhaps the most remarkable act of artistic solidarity that Gappah performed this year is striking a one-of-kind deal with her UK publisher to make her book available in Zimbabwe. Readers in Harare, Bulawayo, Gweru, Masvingo, Mutare and Victoria Falls can now buy these books at half the typical markup.

By taking on such a task, Gappah extends the sphere of the author’s responsibility considerably. It’s one thing to publish a book and be content to let the book do its usual rounds through London, New York and Paris. But it takes a certain kind of artistic commitment to take on the financial risk of making one’s books available to African readers. Gappah has said she’s learned a lot from the experiment and hopes it becomes the springboard for a sustainable book distribution model. We hope so too.

This award is really just a thank you note to Gappah for giving us, first and foremost, the rare gift of beautiful stories. But we would also like her to know that her contributions to a sense of community around African writing and literary culture have not gone unnoticed.

We wish her success in the coming year and can’t wait to read more of her work.

Ainehi Edoro

Chicago. Dec. 2016.

********

Image via Petina Gappah’s Facebook page.

Eddie Hewitt December 19, 2016 12:21

Superb choice, Ainehi. And you have set out your rationale so well, and how uplifting Petina Gappah is, through her approach to writing, her character and her wonderful books. This is a great day for African literature.