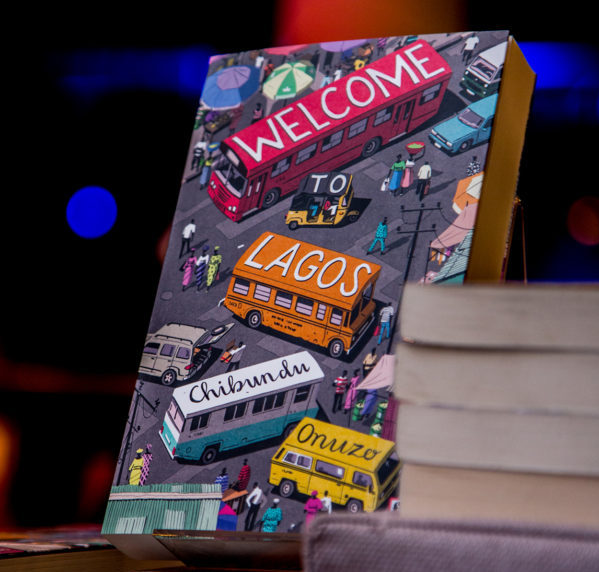

For almost two-thirds of Chibundu Onuzo’s new book, one searches in vain to find the source of the title, Welcome to Lagos (Faber & Faber, 2016). Was it ironically chosen to direct the reader on some chase of relevant nuggets of the city’s peculiarities or selected just for the foreboding it suggests to those already familiar with the city’s reputation for unpleasant surprises? Or was Onuzo merely influenced by the British mini-series of the same name which aired in 2010 to wide acclaim? Each of the reasons throw up different clues, but the content of the work establishes the author’s dedication to Lagos as a place of real historical value but more importantly as a stimulating one for a modern literary setting.

What one finds, however, is an engaging tale of two, then three, then four, later six (and then too many to count) young and old Nigerians whose paths cross first by mistake, and then by a series of events that engulf and then shape their lives, their families, acquaintances, and the country at large. It is a human story which is lent fictive verisimilitude and intensity by the cultural, social, political and ethnic backgrounding that the Nigerian space provides. Two friends escape from the army in the South-South where militants and military men jostle for authority and crumbs from the national cake in Abuja. On their way to Lagos, they run into two other individuals with whom they spend the rest of the novel exploring nuances and crannies of life, politics, and Nigeria’s special brand of corruption.

Somewhere in this story is friendship, and romance, and love, lust, murder, intrigue, politics, and all what you’d expect from a story taking place in a city as mercurial and intense as Lagos. But what moves the story forward from start to finish is a series of other individual attributes: selflessness, curiosity, rebellion, greed, redemption, and more. The story is an exercise in empathy re-allocation. Is an attempted rapist worthy of love and trust? Could a greedy politician caught with $10M in his custody be trusted to really be an altruistic philanthropist or one to give his life for another? Could people of different ethnic groups work together for a common cause while in the presence of confiscated foreign currency with which they could do as they please?

In the book, as in real life, Lagos is “as one giant bin, filled with empty Coca-Cola bottles and cellophane wrappings. There was a bustle and a buzz but not in the purposeful manner of New York or Tokyo. This was the aimless energy of a crowd, static electricity flowing nowhere, sparks rising from too many bodies jostling in too little space…” The Third Mainland Bridge was “a concrete millipede curving over the lagoon for miles, built by an African government, a feat of engineering unnoted by the rest of the world.”

“In Ikoyi, the streets were… quiet… The politics of road signs were largely ignored in this part of the city that had once been a British reserve, no blacks allowed except as cooks and houseboys, dumb waiters mixing gin with spit and tonic. Even now, there were still many whites in Ikoyi, embassy staff mostly, tethered to their compounds by security warnings, corralled to a narrow radius of vetted bars and restaurants…”

One gets the feeling that Ms. Onuzo’s choice of the title was for the private delight of being able to describe Lagos in new words for the international reader.

***

In the eighties Nigeria, a series of works were published under the “Pacesetter Series” by Macmillan publishers. These were novels of popular fiction written by notable African authors. The series began 1977, and at the end of its run had published about 130 titles.

One of them was Sweet Revenge by Ulojiofor, Victor A, which I read as a teenager. In it, a group of young students take the law into their hands when they stage a highly successful ambush of a bullion van in order to prove a social point. The story, written in a highly accessible language and fast-paced thriller style brings the reader, scene after scene, onto the side of the rouge youths whose actions, in another life, would be condemned as extremely criminal.

I don’t remember much of the arc of the story anymore, but the feeling I took away from the experience of reading it has remained, freshly stimulated on contact with Chibundu Onuzo’s energetic second book which is equally half didactic, half city thriller. The difference in the two works would be of length and style. Of length, there is not much complaint. It is a long work, with 70 chapters. But reading it on Kindle inoculated this reader, somewhat, from the intimidating feel of the distance needed to get to the end.

Of style, there is a short treatise that needs to be written about Onuzo’s use of language: English, Nigerian English, and the Nigerian languages featured in the work.

Of the first, here are my favorite excerpts:

“They boarded a bus, a metal carcass on wheels with a floor like a grater, coin-size holes through which you could see the road streaking by.”

“The door shuddered, termites scuttling, alarmed and incensed by this assault on their food.”

“She had been a kitchen worshipper once, a nun in the order of the stove. She knew now that the pillars of her old life were decorative columns, supporting nothing. Yet she gasped when she opened a cupboard in their new home and saw a grater, shaped like a small pagoda, with four different hole sizes dotting its sides. She grasped the ends of a rolling pin and ran it up a wall, imagining a lump of dough, spread flat under its pressure. She did not realize till then how much she had missed her kitchen.” (Kindle location 1205)

***

Onuzo does something truly remarkable in her attempt, in Welcome to Lagos, to render Nigerian words and phrases in their true writing forms. I will address her success or lack thereof with regard to Yorùbá in a minute, but I was even more impressed by a seeming stubborn insistence on keeping Nigerian English expressions the way they would otherwise be written (or spoken) in Nigeria today, in defiance of what must have been an editor’s interference at Faber & Faber.

Here are a few:

“My credit is going.”

“Who is making noise?”

“His screen lit up. One missed call from Chike, who was so expert at flashing that the phone never rang.”

“Can you borrow me a pen?”

With Yorùbá, she succeeds to a lesser degree, but not for lack of trying. All the Yorùbá words, names, and expressions in the book are marked with diacritics, but not always the appropriate ones. Where it works, it works very well:

“Ah, ọmọ Íbò tiẹ̀ ni ẹ́”

Five is too much. Ìbá jẹ́ pé ẹ̀yin mẹ́ta péré ni…”

‘Of course. The two of you won’t be able to see eye to eye. Irú ọ̀rẹ́ wo l’ọmọ Yorùbá nṣe pèlú ọmọ Íbò?’ Sandayọ’s question could not be posed in English. It would be robbed of the solidarity he was trying to build. ‘Yẹmi,’ he said, after the pause had extended beyond hope of reply, ‘Ṣé o gbọ́ Yorùbá?’

But where it doesn’t work, names are incorrectly marked, leaving them marked by the eternal possibility of ambiguity, which is a present threat in Yorùbá writing. For examples, in names like Yẹmí or Fúnkẹ́ written as “Yẹmi” and “Funkẹ” respectively. There are some (as there already are) who would say that making an effort is progress when measured against not trying at all, while the tempting response would be that not trying might be better than introducing needless ambiguity. Both arguments miss the point that this should not necessarily have to be the problem of the author, but of the editor and the publisher.

Yes, author prompting won’t hurt either.

In Teju Cole’s latest book Known and Strange Things published by Random House which I reviewed here, extra care was paid to correctly write French, Swedish, German names (Furtwängler, Tété-Michel Kpomassie, Florian Höllerer, Tomas Tranströmer, Galápagos, etc) to appropriate conventions, while those of Yorùbá were left unattended. To this disappointing occasion, I had remarked that we may have become too “apologetic about insisting on proper writing of African languages in literature. The writer, certainly, at this height of his literary career, stands in a great position to influence this change” and has refused to do so. Mr. Cole did not like that localized criticism, attributing it — at a recent get-together — to “crankiness” on the reviewer’s part. But he is not alone in this transgression, so Mr. Cole shouldn’t have taken it so personally. A cursory look at work by new African writers shows how much deference is placed, consciously or not, in writing foreign names to appropriate conventions while the same courtesy isn’t paid to our own. It is time to stop putting all the blame at the foot of our Western publishers!

Chibundu Onuzo, being able to get away with what she did in this work published in the UK by Faber & Faber, deserves strong commendation, and a second one for not being a Yorùbá writer herself. Her defiance acknowledges what is at stake and approaches it with deliberate intention. Ayọbámi Adébáyọ̀’s forthcoming book takes it up one more notch by having the author’s name written properly on the cover, the first time in recent memory by a Nigerian (Yorùbá) writer publishing in English. The future in which book titles (See: Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives) are written according to proper conventions of their source language(s) would be an interesting one indeed.

***

One other thing delights this reader, above all, is the imitation of art and life.

A certain Chief Sandayọ in Onuzo’s book, on whom much of the story turns, keeps his $10M steal in an underground bunker away from sight, and to disastrous consequences. In real life, the EFCC, a Nigerian crime-busting law enforcement commission, earlier this month, found a haul of $9.8m and £74k in the bunker of the former Group Managing Director of NNPC, Mr. Andrew Yakubu in Kaduna in like circumstances. The close approximation of the dollar figure in both instances, among other coincidences, brings Onuzo as close as she would get to being a prophet.

Welcome to Lagos? No, welcome to Nigeria.

********************

Title: Welcome to Lagos

Publisher: Faber and Faber

Buy: amazon

********************

Post image by Blayke Images

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún’s work has appeared in Aké Review, Brittle Paper, International Literary Quarterly, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, and recently in Literary Wonderlands, an anthology edited by Laura Miller. He is the winner of the Premio Ostana “Special Prize” 2016 (awarded in Ostana, Cuneo, Italy) for his work in indigenous language advocacy.

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún’s work has appeared in Aké Review, Brittle Paper, International Literary Quarterly, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, and recently in Literary Wonderlands, an anthology edited by Laura Miller. He is the winner of the Premio Ostana “Special Prize” 2016 (awarded in Ostana, Cuneo, Italy) for his work in indigenous language advocacy.

Thoughts on “Freshwater” « ktravula – a travelogue! April 26, 2018 06:23

[…] my thought on this pervasive deficiency in contemporary African writing in past essays (see 1, 2, 3), but particularly in this recent talk given in Korea about the subject). If we care enough to […]