“He never left a city without getting a souvenir for Mama. Lace from England. Shoes from Milan. Perfume from Turkey. Indian spices. Moroccan headgear. Leather bags from Kano.”

***

The sun had not risen when he left Lagos. The long limbs of twilight played a slow game of police-catch-thief with the first signs of daylight. A medley of bad roads and needless, countless checkpoints manned by hungry-looking policemen more concerned with lining their pockets than national security ensured that, sixteen hours after he drove past the Agba Meta, he was only just approaching the Ring Road axis of Benin City. His arms were beginning to ache. He had never driven over such a long distance before. He had no complaints though. He was behind the steering wheel of a car which had papers bearing his name and passport. Mama would be proud. He had arrived Lagos with Mama’s blessings, a rucksack of clothes several sizes too small, and two crumpled one thousand naira notes slightly discolored from their long vacation in a knot of Mama’s wrapper.

Life was now good to him but, at first, Lagos had been cruel to him, had shoveled king-sized servings of misfortune down his throat with reckless abandon. He had spent his first night under a bridge at Ojuelegba, kept wide awake by a zealous orchestra of mosquitoes and the stench of marijuana and piss. In the morning he discovered the money he had hidden in a sock at the bottom of his bag was missing. The sock had been emptied and replaced.

Lagos 1-0 Osayuki.

A lot of water had passed under the bridge of his life since that sleepless night. Each day, he had wandered the streets of Lagos in search of a job suited to his meager qualification, and each night, he had washed grimy Danfo buses. He would never forget the plate number of the first yellow bus he washed. AG904IKJ. The bus driver was a burly Yoruba man, with hairy armpits and a hairless head, who reeked of dry gin and paid him two badly faded fifty naira notes. He had not lacked places to rest his head because, if there was one thing Lagos had in abundance, it was bridges. Bridges sprouted from the ground like ripe boils and he rested under a different bridge every night. The sound of rotating tires and tooting horns overhead made sure he never had a good night’s rest. By his second week in Lagos, his cash reserves began to run low. He took his breakfast of bread and Pepsi off the menu. Unripe boli and groundnut washed down with two sachets of water at five o’clock had to suffice. Driven by hunger and the determination to get some form of employment, however menial, he set out earlier and walked longer distances in his search for a job. And then his tired feet took him to Ladipo market where he found employment as a sales boy at a spare parts shop. The importance of the job to his survival in Lagos was not lost on him. He worked long hours during the day, sorting out new arrivals, taking stock of previous consignments and auditing books of account which were an absolute mess. The years spent listening to Mama haggle the price of dry pepper, fresh tomatoes and second hand clothes came in handy as he couldn’t be negotiated into a corner by customers who lived for rock bottom bargains. He often worked late into the night and early hours of the morning. The shop became the first roof over his head when the sales manager, who lacked the trademark gusto for this business of his Igbo kinsmen, an enthusiasm which he replaced with an appetite for fresh palmwine and peppersoup, gleefully granted his request for permission to sleep in it at night.

In spite of the fact that he had fled the clutches of its noisy streets and bridges, Lagos begrudged him a good night’s rest. On most nights, he had barely laid on his mattress which consisted of two cartons spread on a bench before the shrill voice of a tambourine-wielding evangelist, declaring that the end of the world was at hand, pierced the silence of the morning and chased sleep from his eyes. At the end of his first year, the Ladipo market branch of Chimezie Ventures, for the first time in six years, had tidy books and even turned in a small profit. He was promoted twice in the twelve months that followed, and at the end of his second year he got a much-deserved transfer to the head office at Apapa, and everything he touched began turning to gold and lots of profit. He whistled Victor Uwaifo’s “Mammy Water” to drive away the tedium and take his mind off the pain building in his arms. He had been away for too long. Eight years. He hadn’t seen Mama for eight years. Hadn’t heard from her in the last three. The chaos of work and overseas travel had prevented his return home. This trip was long overdue. He had planned to make it last Christmas but end-of-the-year stock-taking and last-minute trouble at the ports held him back in Lagos.

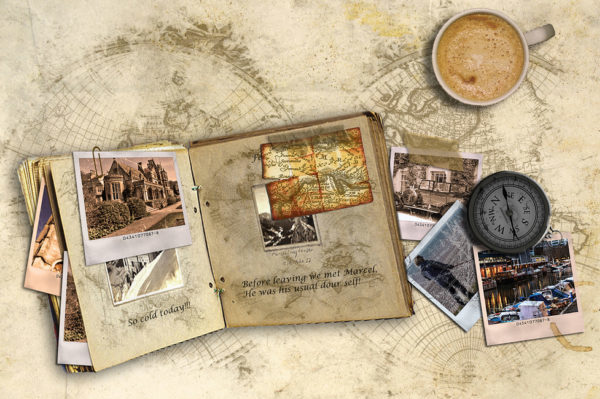

His life had been an adventure and the memories of the years gone by were preserved in the album with the white leather cover resting on the front seat. He had formed the habit of taking pictures. There were pictures from his first trip to England. He recalled his futile struggle to grasp the words which flew out of the client’s mouth at lightning speed. There were pictures from voyages to Japan, China, Australia and New York. He never left a city without getting a souvenir for Mama. Lace from England. Shoes from Milan. Perfume from Turkey. Indian spices. Moroccan headgear. Leather bags from Kano. He felt a lot like Sinbad the sailor. Traffic slowed to a crawl at Mission Road. Christmas was in the air. Carols blared from speakers and packs of mothers, children in tow, bustled from shop to shop in a frenzied search for the best prices. After what seemed like an eternity, he finally eased out of Ring Road and got on the homeward stretch. Airport Road went past in a blur of bright lights, ritzy hotels, loud bars and commuters. For a place he had spent the greater part of his life in, Oko felt unfamiliar. The cratered red roads he once roamed barefooted had been tarred. Modernization had found its way here and had snuffed life out of the rustic scenery. Farmlands had been replaced by buildings which oozed refinement and new money. At the entrance to his street, a garish signboard announced the presence of a hotel. As he made his way down the street, the raucous voices of men sitting at a table lined with green and brown bottles of beer welcomed him home. A weary-looking man with several gourds of palm wine dangling from the handlebars of his bicycle almost lost his balance as he gawked at the vehicle and peered intensely to see if he could recognize the occupant of the big car with tinted glasses. His heart beat a little faster. He could smell home. He saw Mama in his mind’s eye.

He wondered how she would react to his arrival. Would she shed tears of joy? Break into a dance while singing praises to her Maker who lurked in the heavens above? Or throw a tantrum for his failure to show up or at least send a message of some sort? He tooted his horn at the gate he had last seen when he was little more than a teenager with no idea where his life was headed. The gates were cranked open by a boy in a dirty shirt riddled with holes. He couldn’t be more than seven. Osas guessed he was the son of the neighbors. He recalled Mrs Ehondor being pregnant when he left for Lagos. He could not care less about the rundown look of the house. He would take Mama with him to Lagos so he could afford to be indifferent.

The glare of his headlights caused a woman seating on the verandah to shield her eyes with her palm. The figure squinted at first and then let out a squeal of delight when he came down.

“Osas, ó ré nè o,” she shouted.

A dog barked in the distance. She held him in a warm embrace, squishing her flabby breasts into his chest. Mrs Ehondor fussed over him, ran five curious fingers through his hair and pinched both cheeks, all the while making purring sounds better associated with the arrival of a baby than a thirty-year-old man. The boy in the dirty shirt and shorts gazed on, wondering why his mother paid so much attention to the stranger with the big car. She asked how Lagos was and then rebuked him for not remembering them. He begged her forgiveness and promised to settle her soonest.

“Is Mama in?” he asked. The question brought a stop to her rabid movements. He was at sea, his forehead furrowed with confusion.

“Sorry, yes, she dey but she no dey inside house, she dey back.”

He made his way to the backyard where Mama maintained a small garden. He swept the garden with his eyes. Mrs Ehondor must have lost her damn mind in the time he was away. He had made up his mind to give her a severe talking-to when he saw it. A roughly hewn wooden cross standing atop a mound of red earth. He would never see his mother again.

**************

Post image by Notanotherusername! via Flickr.

About the Author:

Daniel Igiekhumhe. Lawyer by day. Writer at night. I am a scribe to the voices in my head and they express themselves at inkyfire.wordpress.com.

Daniel Igiekhumhe. Lawyer by day. Writer at night. I am a scribe to the voices in my head and they express themselves at inkyfire.wordpress.com.

Israel March 20, 2017 09:17

Master-piece, the suspense and imagery are all out of this world... If only universities textbooks can be written this way, everyone will want to read... Lol