It began hours after the Brunel Prize was awarded to Romeo Oriogun on 2 May. Amidst the explosion of cheers, certain posts began to surface. On a few personal blogs. On social media. They all had the same tone, of suspicion, of irritation, of desperation, of anger. Word spreading was this: Someone had won an award for writing poems about gays. The West had given a gay boy an award for promoting their gay agenda. The Brunel Prize win was a campaign to promote homosexuality.

This is Nigeria, a country where asking questions is often inconceivable, where the rage to blame is a norm.

This is a country which, recently, had welcomed and hailed the openly gay CNN anchorman Richard Quest while maintaining violent vigilance on its queer population.

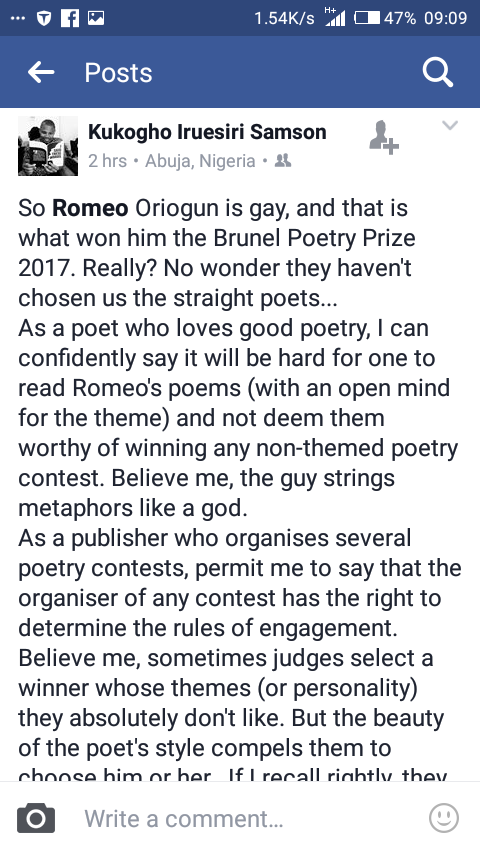

Within days, someone sponsored a Facebook post denouncing homosexuality, calling out Romeo. Soon, another post appeared, sponsored like the first, but with sharper teeth now.

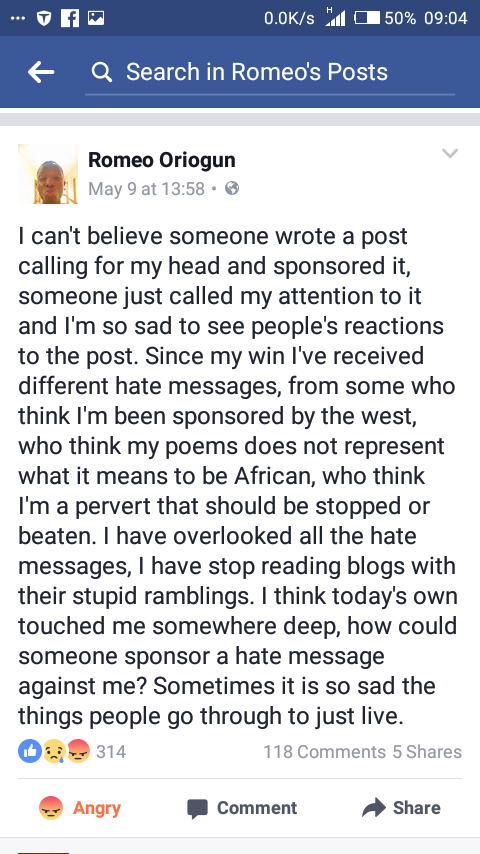

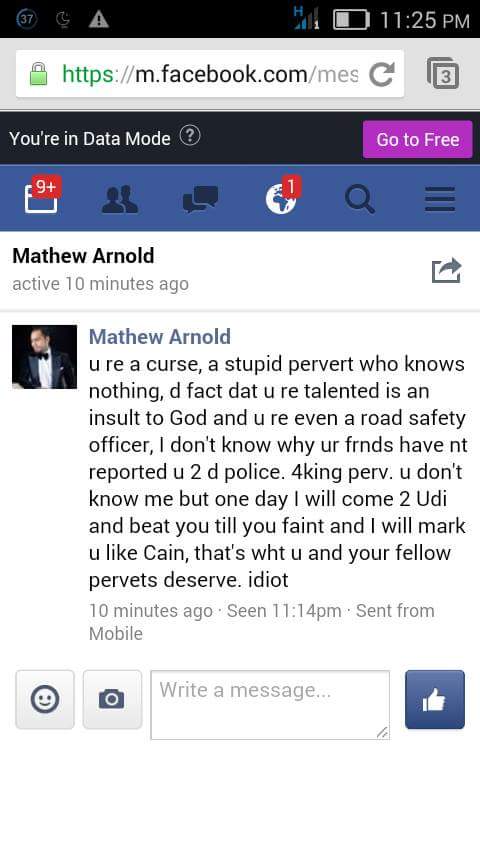

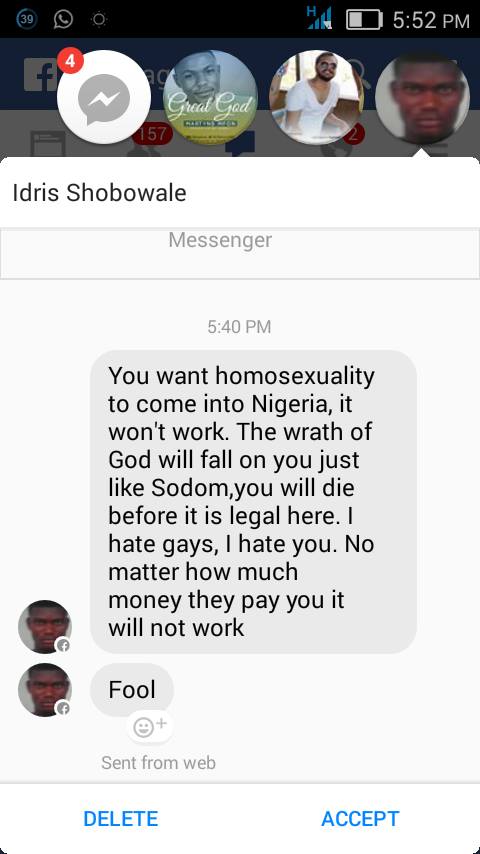

It was when Romeo made a post revealing that he had been receiving not only hate messages in his inbox but death threats—that someone had reported him to his employers and, purportedly, to the police, that because of this, he has had to stay away from work, from his town of residence—that it became clear that the homophobic reaction was not only well orchestrated but was also meant to destabilize.

Days later, Romeo made another post: he shared one of the sponsored hate posts, tagging his friends, asking that they help him report the post, stating that he had already reported a similar post and Facebook took it down. It was urgent. It was an SOS. While some commenters urged Romeo to ignore the posts, the rest, realizing how serious the attacks had become, mounted a barrage of reports.

It quickly became clear that a core of the homophobic bloc who have been harassing and threatening him are people in the literary community, driven as much by their hatred of queerness as by, perhaps, their professional envy. It was a sad twist but also a familiar one.

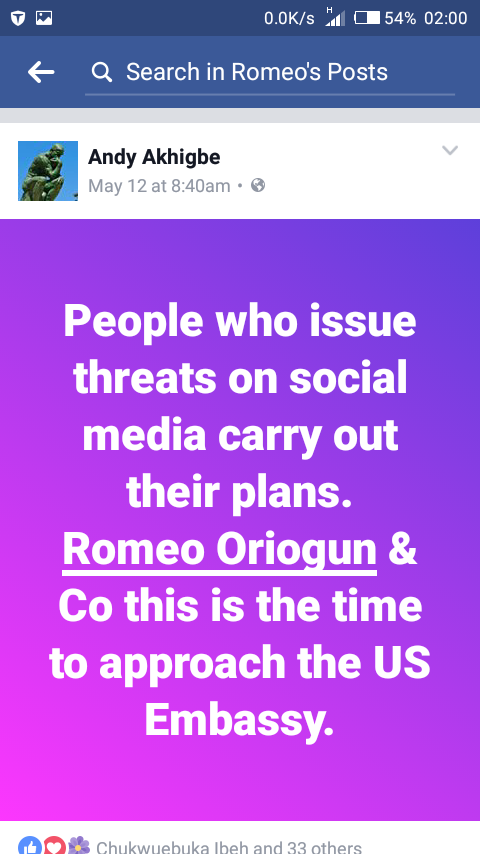

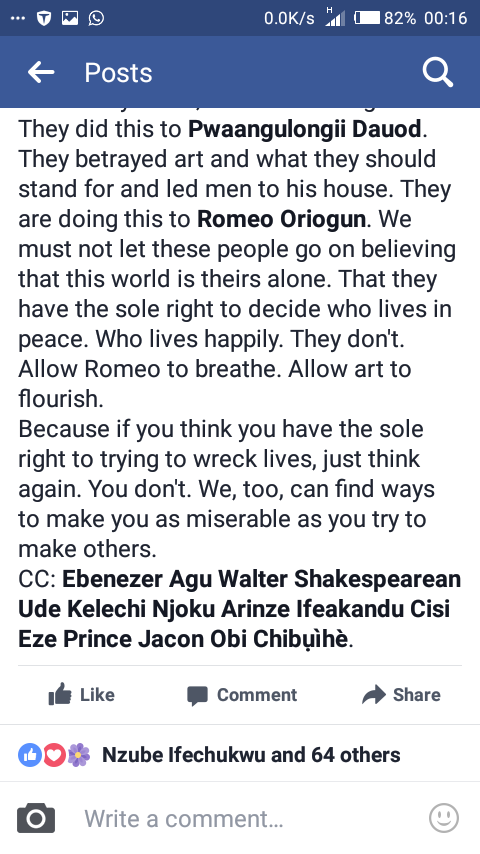

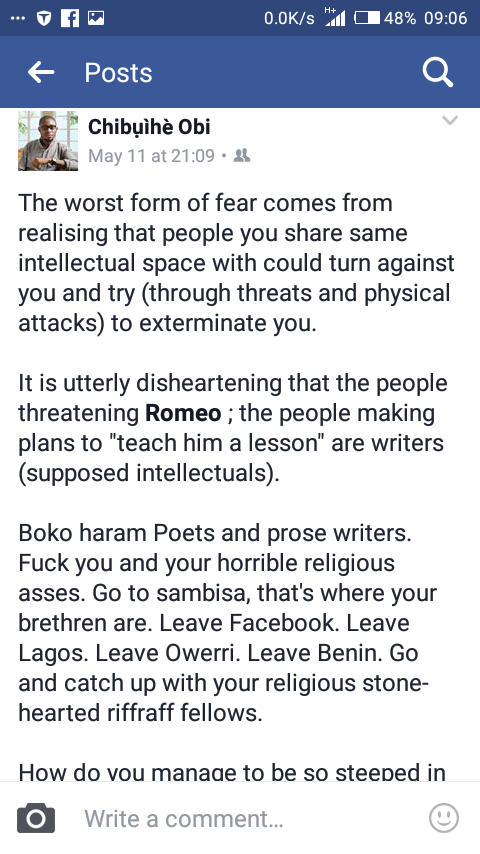

Last year, after Pwaangulongii Dauod’s essay came out in Granta and he had to flee Zaria, he reiterated his belief that it was people in the literary community who had led his attackers to his apartment. If literary people were behind this once again, it was clear what they could do, and what they were doing was already working. The worst of it all was that promise of violence on Romeo.

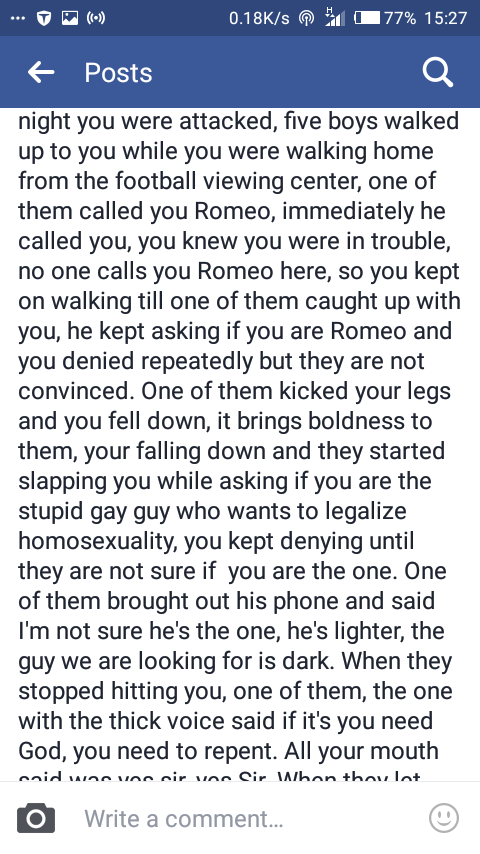

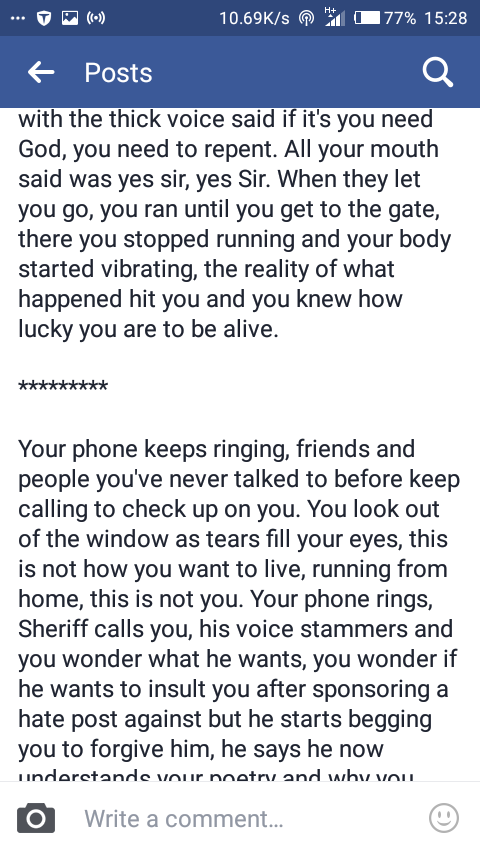

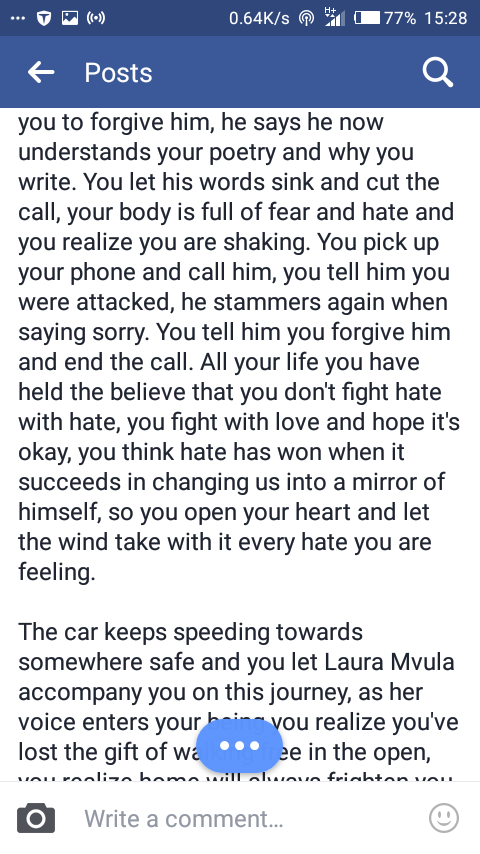

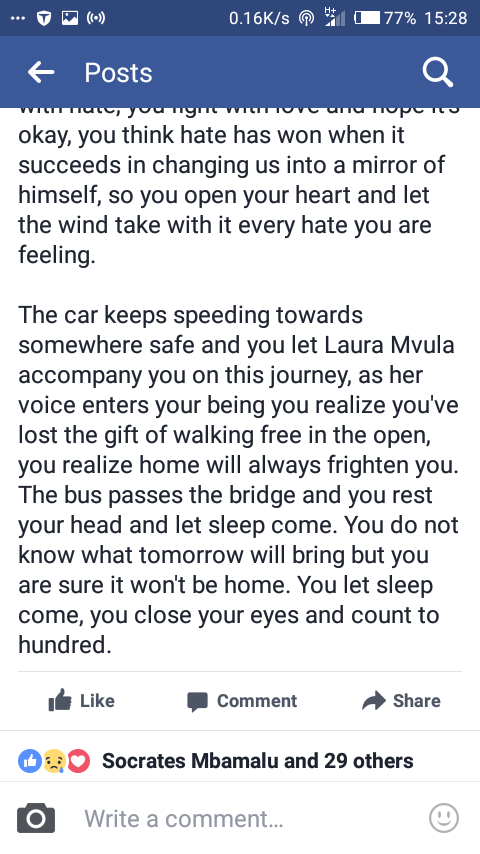

And then it happened. Romeo was assaulted by five unknown men. But it would be weeks later, in the afternoon of 18 May, Thursday, that he would share his experience, in a Facebook post detailed in the second-person. Here is a screenshot from the post.

On 12 May, the LGBTIQ literary group, 14—which in January published an anthology of queer art, We Are Flowers—got hold of screenshots from Romeo’s inbox. The photos circulated privately.

The sponsored posts, the photos, the dismissive, passive-aggressive blog posts—they demanded a response. A response with as much bite, as much ferocity, as much lack of apology.

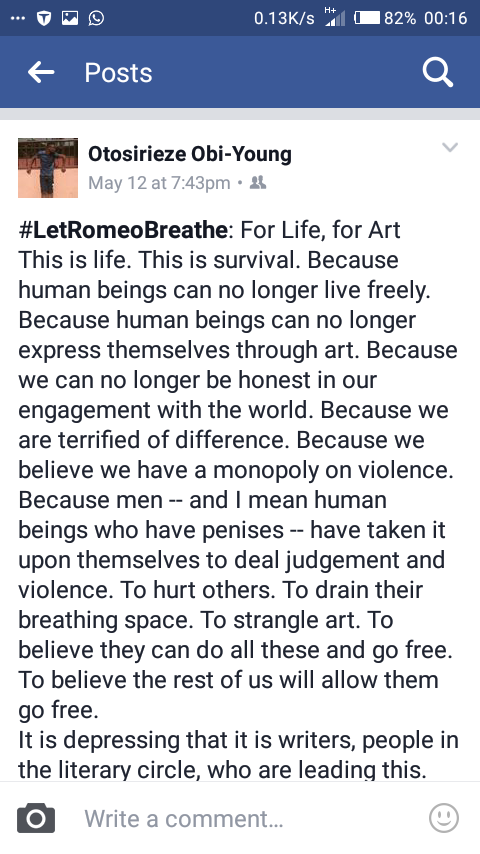

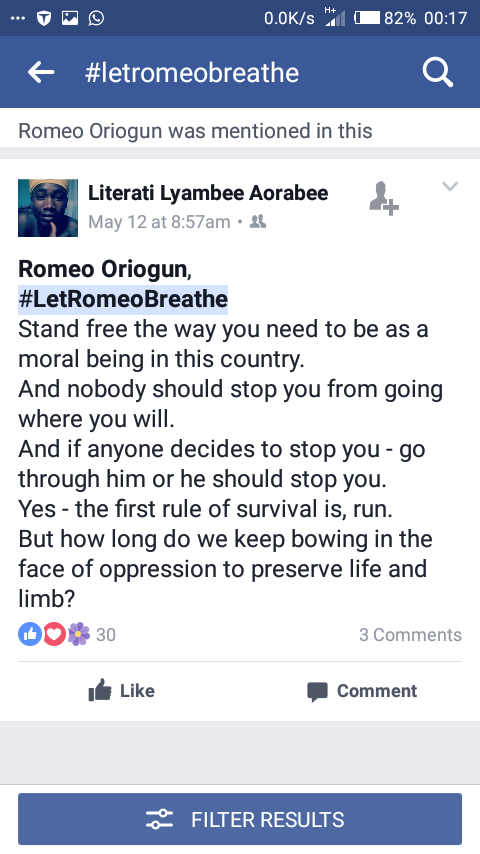

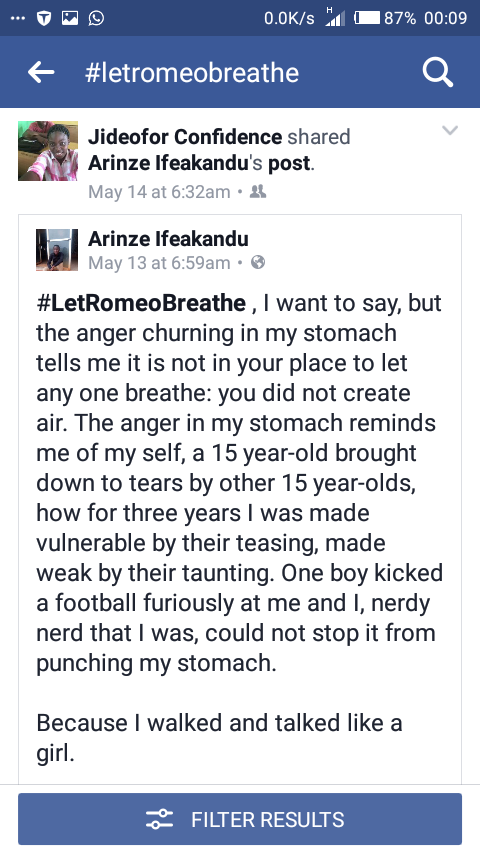

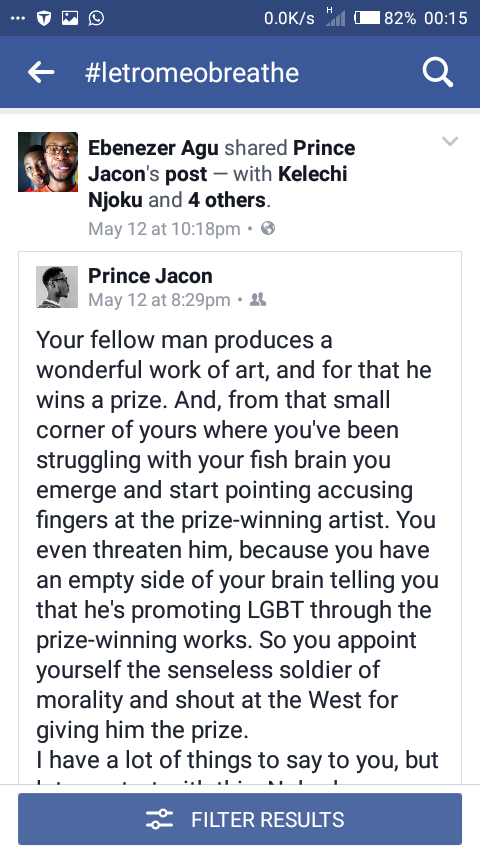

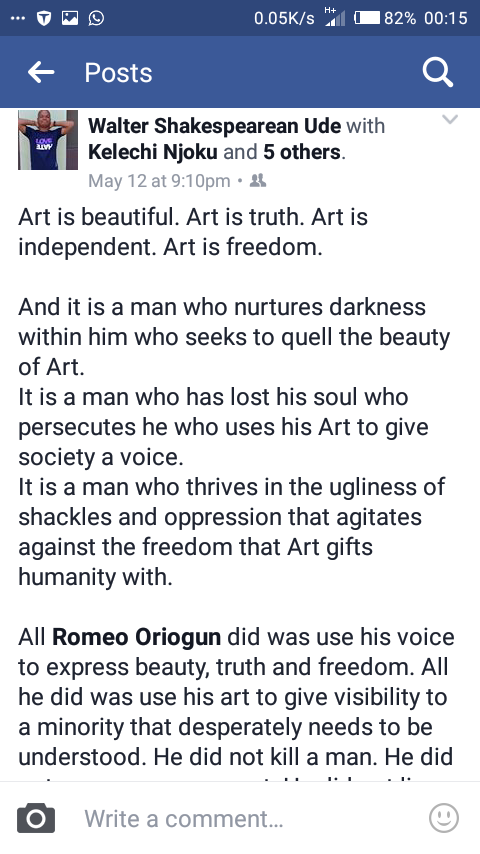

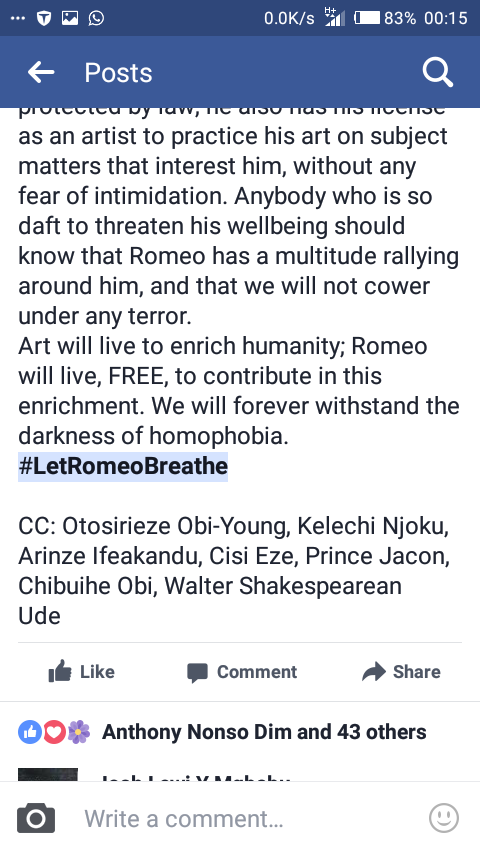

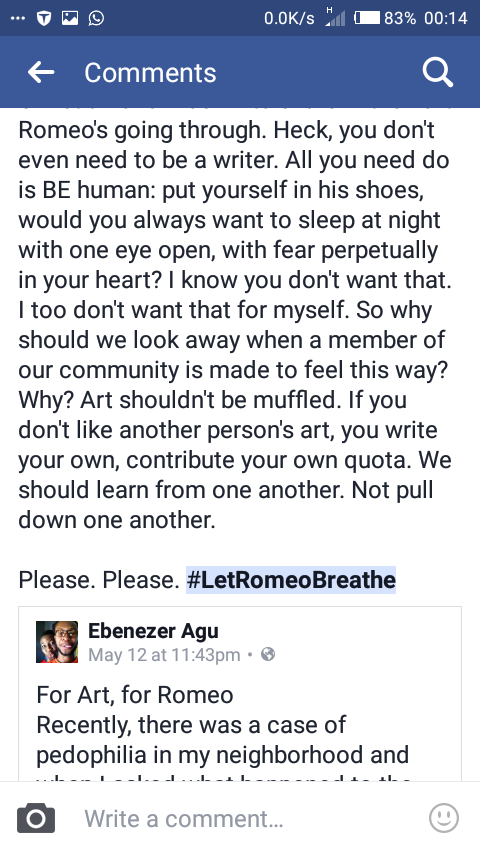

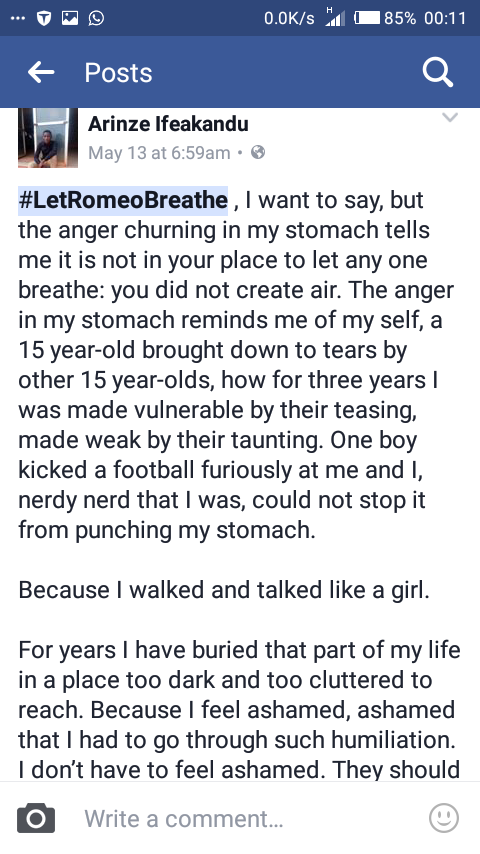

At this time, friends had begun to put up a few posts in support of Romeo, commentaries on the hypocrisy of a national homophobia that accepted a white American man while repressing its compatriots. In the night of 12 May, a post with the hashtag #LetRomeoBreathe went up.

The poster tagged friends, who in turn made similar posts with the hashtag, tagging more friends, sharing and re-sharing, until the solidarity swelled.

The tone of these posts ranged from anger to shock to frustration to more anger to disappointment to more anger. This was the logic: If the homophobes could make such strong efforts at bullying and threatening and attacking, then the solidarity would erect an even fiercer bulwark for Romeo and for Art. The freedom of being, the posts state, must be protected at all costs, and so must the freedom of artistic expression which was seemingly being turned into a symbol of the attackers’ frustration. One of the leaders of the attacks, Sheriff Olanrewaju, after all, had written:

The veil has finally been lifted from the faces of those who hide under the guise of creativity with deft but devilish motives towards the promotion of immorality in Africa.

A phrasing that is an attack on artistic freedom. Which is all the more threatening as he himself is a writer who surely must have a grasp of the sacredness of such a freedom. The solidarity around Romeo was a response to an immediate, formidable threat to both life and art.

Here is the full post of the night Romeo was assaulted by five unknown men.

There has to be a way for the literary community to take the initiative in issues enveloping its members.

On 17 May, the International Day against Homophobia and Transphobia, we published a beautiful, searching essay by the poet and photographer Chibuihe Obi. His piece is a probe into the relative absence—until recently—of literature by Nigerians centralizing queerness. But it also reveals that most dreaded thing bestowed on people who identify as—or are suspected to be—queer: physical harassment, violence. Chibuihe has twice faced harassment because of his poetry. He has been warned to never write about queerness or he would be attacked.

Sometime last year, I was invited to do a reading at Imo State University (IMSU) by a literary society there. During the reading, a particular section of the audience became incensed by the homoerotic inclination of my poems. They yelled and screamed, egged on by a certain Johnbosco Chukwuebuka, a writer with a handful of books to his credit. They threatened to call the police if I didn’t stop. The reading was halted amidst threats of arrest and hostility.

Two weeks after the Owerri Book Festival, an unknown young man stalked me up to the rear gates of IMSU and, when he finally caught up with me, threatened to cut off my penis if I went on to write and promote homosexuality.

As these cases prove, these threats of violence are not empty. These threats and their actualization constitute a morbid violation of not only humanity but of art. They must not be dismissed. They are not isolated cases. They build up to that scar that Nigerian artists have long faced in their country: silence. The need to shut down the ones who speak. This need that took Dele Giwa, took Saro-Wiwa, sent Soyinka to prison, continues to harass Okey Ndibe.

It is a human thing, but this kind of silence is also particularly Nigerian. We deliberately shut up or are forcibly shut up. We are accustomed to having a few speak for us, to allowing an even fewer number take the heat. Every Romeo who has been assaulted, every Chibuihe who has been harassed for speaking: every time that the literary community fails to stand up to these aggressions represents yet another concession of art to anarchy.

And this should not go on.

Like these young writers who have stood with one of their own, Brittle Paper stands with these artists and with queer Africans who daily face a negotiation over life for being who they are. They must be allowed to be and breathe. Let them breathe.

Kabaka, An African LGBTQI focused literary magazine, seeks your submissions November 12, 2019 15:41

[…] in a country that does not recognise LGBT rights.” Winning the prize was good for him but it became very tricky for the man as being queer in Nigeria isn’t just frowned upon. It’s actually […]