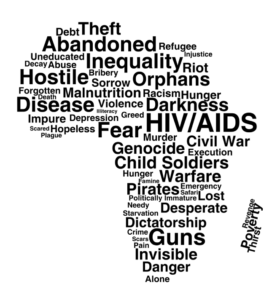

Youth makes you too apt a pupil of coarse lessons it will take decades to unlearn. Your headmistress a family television—ancient, venerable—cased in oak heavy and vast as the Encyclopedia Britannica, entire. Poor, poor pickaninny, pick a program. Poison. Drink in definitions as you sit transfixed on grainy carpet, chin on the kickstand of your knuckles. In looney toons, you are a jungle bunny—drum-bottomed, tuber-lipped—cooning for that rascally rabbit. Savage beneath ivory smiles. In sepia broadcasts, you are cowering darkie to towering Tarzan—a broad-framed, onetime Olympian swooping down from treetop fiefdoms to be your savior, your civilizer. There is a peculiar lull as your agile young mind absorbs these images, so at odds with those of parents and uncles and aunties cum doctors and lawyers and engineers. A chimpanzee familiar is smarter than them all—these spearchuckers, these cannibals. A cruel tutelage.

You were once a Brownie. Awarded a Wilderness Survival Patch for handily identifying which innocuous leaf would inflame skin given the slightest brush. But the school playground at recess is a different kind of badlands—its wild ones wear hi-tops and Kangols, have brown faces that are cousin to your own yet claim no kinship. They hoot and holler. Their tongues—purple or blue or yellowed from time-stamped taffies—lash out. “African booty scratcher. Betchu live in a tree. Bet yo’ mama’s a monkey.” You try for calm, take big, gulping breaths that puff up your lungs with air gone to rot. But you are swinging now, punches wild, some landing, some not. Later, hurting in places unknown, you ask your family why they tease you. Your father, who is a professor and cultural anthropologist, will try for social context, speak of old wounds. Of how they may associate you with treacherous tribesmen who sold their captive ancestors to slavers along Cameroon’s coast. Your Uncle Elias, who drives a borrowed cab and has no papers, will tell you to ignore the ignoramuses: “Eh-eh. These akatas barely go to school; even though it is free. Me, I have a whole masters degree and cannot get work. Nyamangoros! You are better than them. Who cares what they say?” Your Auntie Alexis, who bleaches her skin and married a very fat yet very rich mukara man, tells you Africa is doomed. “We could be strong; but we never unite like the whites. Our foolish leaders sell our countries, our futures, for dix-dix francs. Your schoolmates were born in America. Who wants to be African?” Your mother, who is a psychotherapist and a prolific hugger, will tell you it is because they have yet to learn to love themselves, still so mired in their pocked history. You remind them of all they have lost.

In the 2005 book, Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing (PTSS), a social scientist theorized about the survival mechanisms developed in African American communities in reaction to multigenerational oppression during centuries of chattel slavery and institutionalized racism. One of the three key behavioral patterns of the Syndrome is racist socialization i.e. internalized racism which is characterized by learned helplessness, literacy deprivation, distorted self-concept, antipathy or aversion for the following:

-

The members of one’s own identified cultural/ethnic group.

-

The mores and customs associated one’s own identified cultural/ethnic heritage.

-

The physical characteristics of one’s own identified cultural/ethnic group.

Your 4th grade homeroom conducts safety drills. Students orderly file out from class imagining infernos at their heels or practice futilely ducking beneath desks in the event the Soviets should do the unthinkable. Your teacher, Ms. Bunches—she of the closed-book pop quiz and nightly essay assignment—performs spot hygiene checks after roll call. They say she can smell nasty at 30 paces. You watch her face for signs. For a tell-tale twitch of her high, pinched nose. But there is no emergency alert system. This is not a drill. She sidles up to student desks, ostensibly collecting homework, pausing, sniffing out the secret stink that had beckoned her from her blackboard. Flop sweat beads, then trickles down your back. She is behind you now. You clamp down your arms. All too late. “Raise them,” she says, head bent to yours. A chalky stick of deodorant materializes, flaking white like her hair. “You need this,” she whispers. “You’ve got the African smell.” Head bowed, you let her mark you; never quite sure what she means by “African smell” but somehow knowing it reeks of dank humiliations and day-old bologna, moldering.

RIGHTGUARDSURESECRETOUTLASTGOLDBONDIRI SHSPRINGDEGREEDOVEALMAYAXENIVEASILVERP ROTECTSPEEDSTICKBRUTBANJOBANDRYIDEASAN EXBODODORITCRYSTALFRESHJASONARM&HAMM ERRIGHTGUARDSURESECRETOUTLASTGOLDBOND IRISHSPRINGDEGREEDOVEALMAYAXENIVEASILVE RPROTECTSPEEDSTICKBRUTBANJOBANDRYIDESA NEXBODEODORINTCRYSTALFRESHJASONARM&HA MMERNONONONONONONONONONONONONONON ONONONONONONONO!!!!!!!!

Another February. Your classroom plastered with posters on BLACK ACHIEVEMENT—all caps imperative. Inventors and innovators that gave us pencil sharpeners and peanut butter, blood banks and traffic signals, street sweepers and dustpans. But something is new this year: portraits of African royals from antiquity, graciously supplied by a prominent brewery. King Tenkamenin of Ghana; Makeda, Queen of Sheba; King Mansa Kankan Musa of Mali; Queen Nzingha of Matambo; King Shamba Bolongongo of Congo. A bevy of tongue-numbing names like your own to be memorized along with the litany of Charles Drews, Garrett Morgans, Ida B Wells, and Mary McLeod Bethunes. Eyes unblinkered, your classmates look at you anew. Something like pride seizes you. But memories are short and March rolls in. The continent is on the news once more, embroiled in another far-flung war. Lenses zoom in on HD atrocities in the here and now. Black History. Black Present.

In grade school, you know that you are smart but never pretty. There are always more obvious contenders: Taniesha, pussy-eyed with long, Cherokee-blood good hair; Kiesha, who let DeVante peek at her panty-drawers behind the slides. Rom-com dream girls never look like you. Then there is a PBS series starring you or at least your distant relations. Beautiful Zulu queens: courtly, coveted. Your parents let you break night for “educational viewing” as you are their Gifted and Talented child—a blue-ribboner in Olympics of the Mind. You fall asleep on the couch dreaming. The next school day, boys froth with talk of Zulu girls and their Hottentot teats (bared by the BBC, for historical accuracy). Yo, you see that red-bone with the bee stings? You see that mami with the milk jugs swangin’ like um-dada-um-da. Titties. Tetas. African Tatas. Heads swivel. Eyes zoom in on your frame. It’s shocking being seen all at once, by so many. You flush. Crossed-arms cover what has yet to develop. For years, while Taniesha gets hickeys at the back of the bus, while Kiesha gets a baby bump, you get A’s and B’s but no kiss after prom. For you are African, and by definitions, unsightly.

look like you. Then there is a PBS series starring you or at least your distant relations. Beautiful Zulu queens: courtly, coveted. Your parents let you break night for “educational viewing” as you are their Gifted and Talented child—a blue-ribboner in Olympics of the Mind. You fall asleep on the couch dreaming. The next school day, boys froth with talk of Zulu girls and their Hottentot teats (bared by the BBC, for historical accuracy). Yo, you see that red-bone with the bee stings? You see that mami with the milk jugs swangin’ like um-dada-um-da. Titties. Tetas. African Tatas. Heads swivel. Eyes zoom in on your frame. It’s shocking being seen all at once, by so many. You flush. Crossed-arms cover what has yet to develop. For years, while Taniesha gets hickeys at the back of the bus, while Kiesha gets a baby bump, you get A’s and B’s but no kiss after prom. For you are African, and by definitions, unsightly.

An Admissions counselor at your dream college speaks of wondrous opportunities. She leans in to share a moment with you, future Ivy-Leaguer. “Your kind does so well here,” she murmurs, adding confidentially, “Not like those others.” Her smile is knowing. So you smile back. Are you smiling in agreement? In gratitude? Because those who once hurt you are now made small? You’re undecided. But it’s not like the moment will stand isolated. Its twin comes as an African-American Financial Aid officer frowns down at your application, tells you, “you people” are why her son can’t go to college. She stamps an angry approval on your paperwork. So you smile. Are you smiling in agreement? In gratitude? Her colleague pulls you aside, tells you, “Chile, she just mad her son got caught up in the streets.” You smile. But sometimes your throat constricts, your face goes tight, quick-like.

College tests you. There are Swahili 101 electives, classmates in bantu-knots, and monthly African Student Union meetings. Yes! Yet  certain lessons are trying. A media studies class schools you on symbolic annihilation—the omission, the mis- or under-representation of whole peoples in book leaves, in film reels. And you remember your skin is the color of redaction. You remember confusion as old elementary school “friends” poke you online. Who are they? Their names are never next to yours in class photos, in yearbooks. Were you friends? Where is the evidence, the proof of life? Hives punch through your skin like pissy ellipses. Scratch them raw till a patient school therapist explains that this is how a body purges upset. No matter how long-suppressed.

certain lessons are trying. A media studies class schools you on symbolic annihilation—the omission, the mis- or under-representation of whole peoples in book leaves, in film reels. And you remember your skin is the color of redaction. You remember confusion as old elementary school “friends” poke you online. Who are they? Their names are never next to yours in class photos, in yearbooks. Were you friends? Where is the evidence, the proof of life? Hives punch through your skin like pissy ellipses. Scratch them raw till a patient school therapist explains that this is how a body purges upset. No matter how long-suppressed.

Try and try to forget. Your memory had always been fuzzy, tending towards breaks in the transmission, bald spots of time you had jokingly dubbed “selective amnesia.” But still moments remain. You, itty-bitty—all nappy plaits and teddy bear eyes. A soft one you were. Keen on gold stars. Undone by scolding. When you made mistakes—as children are wont to do—there were inconsolable fits of despair. Your worried mother gifted you a children’s book on self-esteem whose pages held a mirror. She bid you look. Sing-songing of all the ways in which you were wonderful. You are smart. You are beautiful. You are worthy. Your agile young mind struggled to absorb those images, so at odds with those of books and television, of schoolmates and teachers alike. The mirrored book grasped tight in your trusting hands. “Look again, child,” Mama told you. “Look.” But you were gumdrop young: tender-headed and tender-hearted. You turned from your likeness.

*************

“Schoolyard Cannibal” is not part of a short story collection titled Walking on Cowrie Shells published by Graywolf. Buy the collection: Amazon | Bookshop

[The JRB Daily] JRB Contributing Editor Bongani Madondo up for Brittle Paper Literary Award – The Johannesburg Review of Books August 23, 2017 14:06

[…] “Schoolyard Cannibal,” Nana Nkweti, prose-poetry (Cameroon) […]