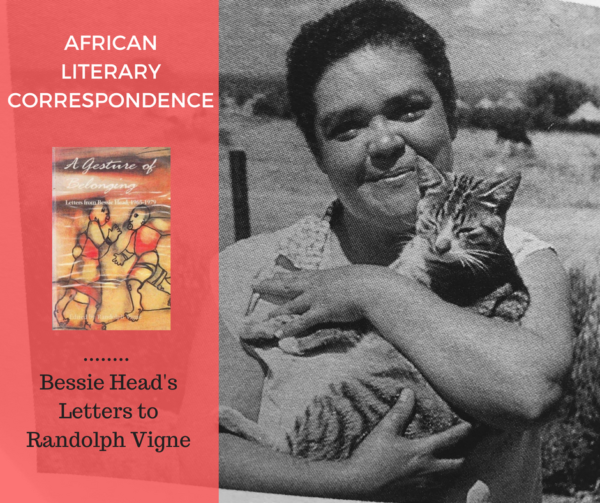

Brittle Paper recently published a feature on Bessie Head’s 1991 collection of letters, A Gesture of Belonging. In that essay, Ainehi Edoro took me back to two years ago when Bessie’s letters were the centre of my life. Her story reads like that of my grandmother, my mother and many black women that I know. Her letters, written to Randolph Vigne, unsettle and tell you who you are, and together they constitute a testament to writing from the margins. Writing no matter what. Writing and beauty. Bessie Head would have been 80 this year. She died in obscurity in a hostile Southern Africa when she was 49. She has been dead for 31 years but continues to move those of us who live marginal lives.

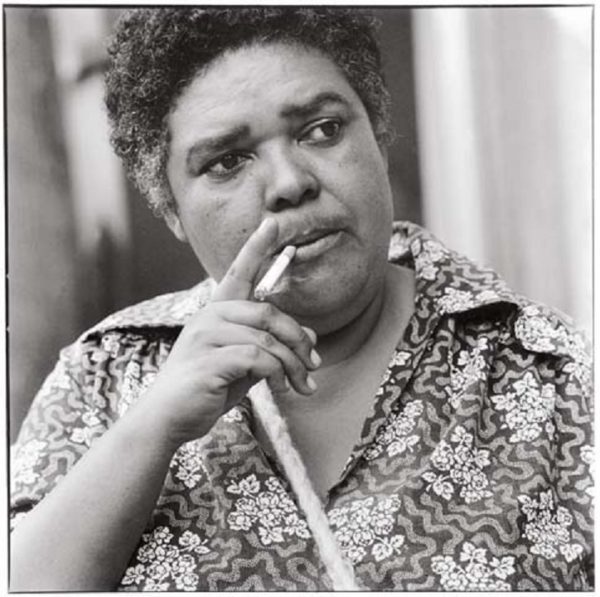

The pain in her letters makes her living to 49 a wonder. It is plausible that she could have died younger. Fleeing the madness of South Africa’s racist society, she moved to neighbouring Botswana where she carved a painful life of continued rejection and madness. Her letters reveal her tenacity and wit in the face of constant precarity. Her only joy was writing the beautiful work that has become the hallmark of Southern African literature. Still, her letters remind us that both South Africa and Botswana did not want her. Born of black and white parents, she fitted into neither the narrative of the Africanist ideology of her early years nor the race purity propagated by South Africa’s Apartheid system.

Bessie Head’s flirt with madness is at once tragic and liberating. It points to the madness of binaries and society. Her madness is our madness. Bessie was mad because we were mad. Her madness produced Maru, When Rain Clouds Gather, A Question of Power, A Collector of Treasures, The Cardinals, and then these heartrending letters. One understands how, with the much she has pulled together in her art, her work is a crowning glory of African literature.

Bessie wrote through terrible headaches and heartache. In November 1969 she told Randolph:

I feel well now but my whole nervous system is shattered. Sudden and terrible headaches descend on me. I live on a huge assortment of tablets.

The police would routinely bundle her up and hospitalise her, leaving her son in the shadows. Mental health is closely determined by genes, socio-political conditions shaped by inequality, patriarchy, racism, rejection, exile and poverty. Bessie Head lived in the confluence of these maddening currents as Southern Africa imploded under the weight of Western imperialism and Apartheid.

Bessie’s white South African contemporaries were Nadine Gordimer, Andre Brink, and J.M. Coetzee, among others. J.M. Coetzee continues to write in his old age, while Gordimer and Brink had long distinguished careers before their recent deaths. Bessie’s talent received none of the space and privilege which nurtured the careers of her white peers. She fought for publication on her own terms, for payment for her work, space to live, a country to live in, and bare necessities such as food, healthcare and lodging. Her collected letters and writing are all the more beautiful and special for this life of poverty and rejection. Ellen Kuzwaya, Miriam Tlali and other black women of Bessie’s time wrote under similar conditions, their careers constrained by everyday challenges imposed by patriarchy, Apartheid and poverty. Writing on an empty stomach in candlelight was not a challenge that Coetzee had to contend with.

The coldness of Americans towards Maru, “because it pricks like hell over the racial question,” illustrates the general animosity to the themes that she pursued in her work. The poverty and displacement Bessie endured enabled later generations to inherit the incredible texture of her unrelenting critique of inequality and the beauty of everyday village life. The significance of lives made marginal. While Lefebvre theorized everyday life, Bessie Head lovingly depicted it, living it, critiquing it and showing us the possibilities of a close reading of the everyday.

Each letter in A Gesture of Belonging is addressed to Randolph Vigne, but what if we replaced Randolph with our own names? What message would Bessie have for us today and how might that change the world that tormented and railed against her existence? Bessie’s messy life illuminates the possibilities for living and thinking against the grain of our times. She gestures less to belonging and more to possibilities, more to imagining life beyond binaries found in the ghettos of belonging. She gestures to the power of marginal life. And beauty.

**************

About the Author:

Hugo kaCanham teaches psychology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. He is also a closeted novelist. He lives in Johannesburg but his heart resides in his village of Mbayi in Lusikisiki.

Hugo kaCanham teaches psychology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. He is also a closeted novelist. He lives in Johannesburg but his heart resides in his village of Mbayi in Lusikisiki.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions