We finally have an excerpt of Ayobami Adebayo’s Baileys Prize-shortlisted novel Stay With Me. Those of you who have been wanting to get a taste of the book before you read it, this is your chance.

Stay With Me tells the story of Yejide and Akin. Their marriage begins with so much romance and promise. But as the reality of infertility kicks in, their lives become complicated beyond measure.

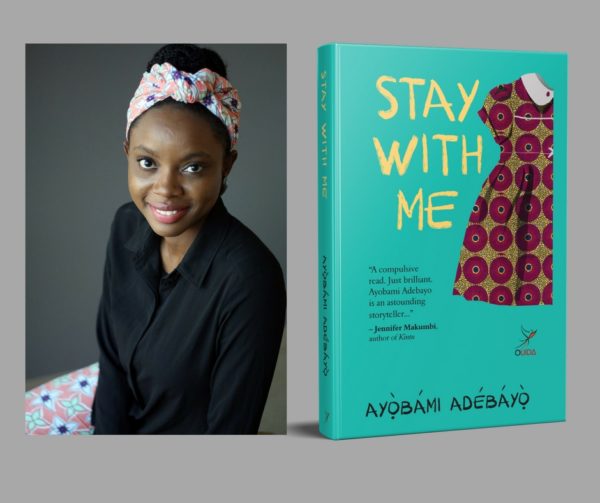

Stay With Me is a widely talked-about debut novel. It’s was a favorite of critics long before it was shortlisted for the Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction. Margaret Atwood loved it! She described it as “scorching, gripping, ultimately lovely.” Jennifer Makumbi, the author of Kintu, enjoyed reading it and said it was “just brilliant!”

If you enjoyed the excerpt, it’s easy to get the book. The novel is on Amazon. Readers in Nigeria can get it through Ouida Books here.

Enjoy!

1

Jos, December 2008

I must leave this city today and come to you. My bags are packed and the empty rooms remind me that I should have left a week ago. Musa, my driver, has slept at the security guard’s post every night since last Friday, waiting for me to wake him up at dawn so we can set out on time. But my bags still sit in the living room, gathering dust.

I have given most of what I acquired here – furniture, electronic devices, even house fttings – to the stylists who worked in my salon. So, every night for a week now, I’ve tossed about on this bed without a television to shorten my insomniac hours.

There’s a house waiting for me in Ife, right outside the university where you and I first met. I imagine it now, a house not unlike this one, its many rooms designed to nurture a big family: man, wife and many children. I was supposed to leave a day after my hairdryers were taken down. The plan was to spend a week setting up my new salon and furnishing the house. I wanted my new life in place before seeing you again.

It’s not that I’ve become attached to this place. I will not miss the few friends I made, the people who do not know the woman I was before I came here, the men who over the years have thought they were in love with me. Once I leave, I probably won’t even remember the one who asked me to be his wife. Nobody here knows I’m still married to you. I only tell them a slice of the story: I was barren and my husband took another wife. No one has ever probed further, so I’ve never told them about my children.

I have wanted to leave since the three corpers in the National Youth Service programme were killed. I decided to shut down my salon and the jewellery shop before I even knew what I would do next, before the invitation to your father’s funeral arrived like a map to show me the way. I have memorised the three young men’s names and I know what each one studied at the university. My Olamide would have been about their age; she too would just have been leaving university about now. When I read about them, I think of her.

Akin, I often wonder if you think about her too.

Although sleep stays away, every night I shut my eyes and pieces of the life I left behind come back to me. I see the batik pillowcases in our bedroom, our neighbours and your family which, for a misguided period, I thought was also mine. I see you. Tonight I see the bedside lamp you gave me a few weeks after we got married. I could not sleep in the dark and you had nightmares if we left the lights on. That lamp was your solution. You bought it without telling me you’d come up with a compromise, without asking me if I wanted a lamp. And as I stroked its bronze base and admired the tinted glass panels that formed its shade, you asked me what I would take out of the building if our house was burning. I didn’t think about it before saying, Our baby, even though we did not have children yet. Something, you said, not someone. But you seemed a little hurt that, when I thought it was someone, I did not consider rescuing you.

I drag myself out of bed and change out of my nightgown. I will not waste another minute. The questions you must answer, the ones I’ve choked on for over a decade, quicken my steps as I grab my handbag and go into the living room.

There are seventeen bags here, ready to be carried into my car. I stare at the bags, recalling the contents of each one. If this house was on fire, what would I take? I have to think about this because the first thing that occurs to me is nothing. I choose the overnight bag I’d planned to bring with me for the funeral and a leather pouch filled with gold jewellery. Musa can bring the rest of the bags to me another time.

This is it then – fifteen years here and, though my house is not on fire, all I’m taking is a bag of gold and a change of clothes. The things that matter are inside me, locked up below my breast as though in a grave, a place of permanence, my coffin-like treasure chest.

I step outside. The air is freezing and the black sky is turning purple in the horizon as the sun ascends. Musa is leaning against the car, cleaning his teeth with a stick. He spits into a cup as I approach and puts the chewing stick in his breast pocket. He opens the car door, we exchange greetings and I climb into the back seat.

Musa switches on the car radio and searches for stations. He settles for one that is starting the day’s broadcast with a recording of the national anthem. The gateman waves goodbye as we drive out of the compound. The road stretches before us, shrouded in a darkness transitioning into dawn as it leads me back to you.

Chimka June 14, 2017 15:34

It doesn't read like something that would keep me awake all night. But I shall give it a try.