1.

UK political parties were in the thick of electioneering when the worst happened. Before Salman Abedi seized the narrative, Theresa May’s incontinent manifesto-making and an unlikely Corbyn surge dominated the news. In the wake of the deadly suicide bomb attack on the aftermath of an Ariana Grande concert at the Manchester Arena, political parties declared a moratorium on electioneering.

Two days later, the moratorium would be lifted, hostilities renewed. Basking in the new, rare positivity surrounding his leadership prospects, Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn, fired the opening salvo: there could be no excuses for such savagery, he maintained, but, crucially, it was impossible to untangle UK foreign policy from the current state of events.

For his troubles, Boris Johnson labelled him “absolutely monstrous.” There was contempt for Corbyn’s speech “across the aisle,” from the Conservative Theresa May to Manchester’s own Labour mayor. Corbyn’s was an absurd position to hold, they maintained. His position was untrue, his timing impolitic.

Mr. Corbyn is of course guilty as charged. He was monstrous, inhuman even. He certainly was impolitic.

What, then, is not monstrous? What is human? What is politic?

2.

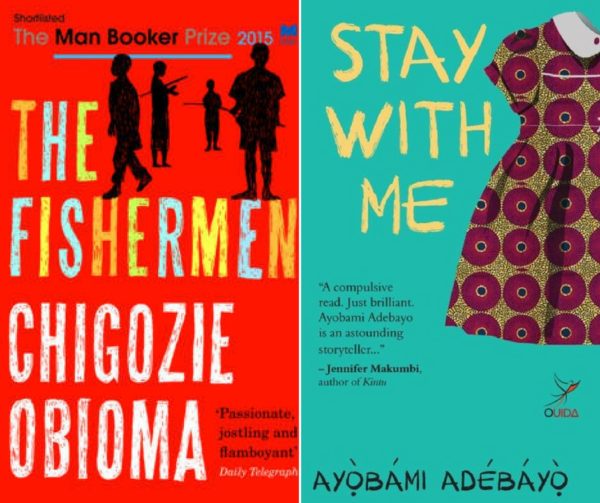

There is a crucial moment in Ayobami Adebayo’s Stay With Me. It is the moment that precipitates Yejide’s eventual estrangement from Akin, her husband. From that moment, her attitude towards Akin changes for the worst, culminating in her eventual departure for Jos via Bauchi. It is the moment she learns from Dotun that her husband is an active conniver in his own cuckolding.

From then on, Yejide’s actions are thoroughly human. In the face of a complex moral and ethical crisis, memory becomes a partisan thing. She begins to see the familiar anew at the very same time that she forgets some other familiar, perhaps sorely disappointed at the mitigation of her agency.

“Akin played me for a fool” (268) assumes new meaning. Regardless of evidence to the contrary, she outsources all culpability for her adultery to Akin in the service of partisanship, as the likes of Boris Johnson and Theresa May seek to outsource all culpability for terrorism to the terrorists, despite the existence of the Chilcot Report.

The tighter the surface area, it seems, the better the othering.

Yejide – conveniently, completely – forgets loathing the woman she’d become (177), the woman who would, moments before she’s confronted with the truth, assure her husband’s brother that his brother “will never know about this [adultery]” (181). She forgets preferring Dotun’s exciting but transparent glibness to Akin’s familiar and therefore colourless assurances.

Who wants constantly to be told they are loved, when there can be praise of the perfect mound of their breasts, the roundness of their buttocks, the seductiveness of their eyes? Who? Yejide forgets dousing with the roguish devil Dotun the fire smouldering in her belly. She forgets stemming the gathering wetness between her thighs with Dotun, not once, not twice, however unter-Akin she claimed him to be, sometimes seeking him out of her own volition.

Having successfully othered Akin, she then begins the process of exacting vengeance by using sex as both an object of desire and subversion.

If Akin’s dastardly connivance with his brother is taken as given, the conspiracy equation still contains another variable whose value must be ascertained. Might Yejide not have batted away Dotun’s ribald advances, especially given her loathing of him? That Yejide acquiesces despite her contempt for Dotun perhaps sublimates the latent beneath the blatant: is great contempt merely a mask for great desire?

In Chigozie Obioma’s The Fishermen, culpability for the tragic turn of events for the Agwu family is ultimately dumped at Abulu’s doorsteps, with fatal consequences for the mad seer. Forgetting here may be more delicate, more prolonged than in Stay With Me, but it is forgetting nonetheless.

Ben, an Agwu child and the narrator, tries to trace the remote cause to their father’s decision to obey the imperatives of his public service job in relocating to Yobe. This link – acknowledged by the directions the narrative will take – is too tenuous, as specious as Obioma’s reading of his novel as an allusion to British colonization of Nigeria.

If the children had not defied parental and societal dictates to become fishermen of the dreaded Omi Ala, perhaps Abulu’s prophecy may never have been prophecised. And if, like Ola Rotimi’s Odewale, Ikenna, perhaps in the crush of teenage angst, hadn’t been gripped by an obsession to avert oracular divinations, perhaps he may not have triggered a familial tragedy.

3.

Quite a few recent Yoruba-novels-in-English seem to turn about children – an interesting trend whose significance it must be tempting to pursue.

Lola Soneyin’s The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives juxtaposes a polygamist’s outsize male ego against a belated knowledge of the very negation of that ego: his impotence. In Stay With Me, the confluence of impotence and desire catalyses the sundering of a young family. In The Fishermen, Emeka Agwu, an only child, is driven to prolificacy by a deep fear of the precipice signified by his onliness. And perhaps we could read into this excess the remote onset of the Agwus troubles. As Adaku says,

What kind of job takes a man away from bringing up his growing sons? Even if I were born with seven hands, how would I be able to care for these children alone?

But is The Fishermen a Yoruba novel in English? It is perhaps a somewhat controversial argument to make, considering a novel like Adebayo’s. Stay With Me’s Yorubaness is straightforward and unapologetic (more on this). There’s not one non-Yoruba character in the novel.

What The Fishermen certainly does, perhaps for the first time in Nigerian fiction, is complicate any easy apprehension of Nigerian ethnicity. Its intra-Nigerian, transethnic treatment of identity is a remarkable breath of fresh air given the reified status of transcontinental hybridity in the totems of contemporary African literature. That this metropolitanism is not prosecuted with Lagos, melting pot extraordinaire, as backcloth, is a remarkable achievement too.

Like the author himself, Ben, The Fishermen’s narrator, is born to Igbo parents in Akure, a middling urban centre in the Yoruba hinterland. Ben is the fourth of six Agwu children. Igbo is the language with which their parents communicate to them, English the language of authority and distancing (in Stay With Me too, Yejide encrypts her communication to Akin in the presence of her in-laws by resorting to English).

The Fishermen is set in Akure and Akure alone, Akure of the 1990s (enjoying a brief temporal intersection with Stay With Me, which is largely set in Ilesa, a similarly second-tier urban area). Unlike Conrad’s Congo, Akure is not simply backcloth, for the very fact that the Agwus don’t live in an Igbo enclave, where the children’s socialization would have been exclusively or sufficiently Igbo.

Consequently, when by themselves and out with friends, the children converse in Yoruba. Their favourite TV program is Agbala Owe. Tobi, a neighbour’s cousin, is given the moniker “eleti ehoro” by Ben and company. Although the fishermen song – a Yoruba song – was invented by a friend called Solomon, “most of the suggestions that eventually made up the lyrics came from nearly every one of us.” If we agree that the children are central to Fishermen, then the argument for it being a Yoruba novel in English is made.

This is not to say that The Fishermen is only a Yoruba novel in English. As the foregone illustrates, it is also, since our pretext is ethnic, an Igbo-in-diaspora novel.

4.

Much has been made of Chigozie Obioma’s similarity to Chinua Achebe. Writing in The New York Times, Fiammetta Rocco explicitly declares Obioma the true heir to Achebe. “As things fall apart and the family’s center cannot hold,” writes Rocco, “Obioma’s readers will begin to recall another work of fiction from Africa.” If Rocco were a football expert, perhaps she’d be the sort who resorts to inventing monikers like “Iranian Messi” and “Uzbek Ronaldo.”

It is true that The Fishermen explicitly invites the association to Achebe and Things Fall Apart. Both Obioma and Achebe are Igbo. Achebe and Things Fall Apart are mentioned in Fishermen quite a few times. For one, there is the standard-issue, widening-gyre Yeats, epigraph for Things Fall Apart as it is for Fishermen’s seventh chapter. Obioma too uses locusts as forerunners of ravage. Following Rocco, The Atlantic’s Naomi Sharp contends that “[t]he title of Achebe’s most famous book, Things Fall Apart, would also serve as an accurate plot description of The Fishermen”.

But “things fall apart” will serve as an accurate plot description for too many novels to be any useful measure of critique. After all, do things not fall apart in Stay With Me, too? Both novels are gory, rambling tales of a family’s unravelling. And that’s the thing: whereas the unravelling in Things Fall Apart is societal, the tragedy in both these novels hardly registers beyond the confines of the families portrayed.

In their use of language, Obioma could not be farther from Achebe. If Achebe’s use of English is soul, Obioma’s is heavy metal. Achebe evolved an easy, distinctly Igbo-sounding English, his debt to oral tradition obvious yet artfully obscured. Obioma’s use of English is anything but easy and has more global than postcolonial pretensions. Achebe would certainly frown at Obioma’s nauseating tendency to immediately translate every instance of his use of indigenous language, no matter how much such translations offset the rhythm of his sentences.

5.

Moomi hissed. “But this is not your fault. It is the children of the orange tree that cause clubs and stones to be thrown at their mother. Foolish children, explain yourselves – explain. Speak the words that are lodged in your mouth.”

Ayobami Adebayo is no heir to Achebe either. It is she, however, who has a less superficial association with Achebe in her attempt to do to English with Yoruba what Achebe did to English with Igbo. In Stay With Me, Adebayo is quite clearly trying to evolve an English with Yoruba sensibilities on the order of Achebe, as the extract cited at the opening of the section makes clear. To what extent she succeeds is of course up for argument.

As in Adichie’s Americanah, the male narrator in Stay With Me is subordinated to the female narrator, with implications for the narrative. Thus, Stay With Me is more likely than not to be apprehended as Yejide’s story, just as Obinze is commonly considered incidental to Americanah. Akin has not been treated as granularly as Yejide and it is mostly from Yejide we can learn, character-wise, the Yorubaness of Stay With Me.

Yejide is a specific type of Yoruba woman, immediately recognizable to anyone who has been to a Yoruba market. Yejide’s sensibility is that of the archetypal saucy Yoruba woman, the sharp-witted shooter-from-the-hip who can instinctively mine gems like “oko ofio” – tiger nut penis, insubstantial manhood – from the swirling depths of language.

The clue to this reading of Yejide appears quite early in the novel, when her unread in-laws have come to “supplement” her. In dealing with her in-laws, she is of course restrained and dissembling, restricting the acerbic wit to the realm of thought, or simply obscuring it by resorting to English, the language of distancing.

“Where is your husband? Do we meet him at home?” Baba Lola asked, looking around the room as though I had stashed Akin under a chair.

Later, in an attempt to steel Dotun’s resolve, she tells him to “stop shaking like waist beads o jere,” a figure of speech Yoruba speakers will easily recognize.

Back in secondary school, Yejide’s knack for fighting earned her the moniker Yejide Terror, but terror can be linguistic, too. In the very dawn of their story at the University of Ife, Akin asks Yejide if she needed a ride back to Moremi. What response does he get? “You want to carry me on your back?”

This terrorism is how, much later, she can respond to Akin with a saucy, sarcastic quip – “Welcome, bridegroom” (which Yoruba speakers will read as “Kaabo, oko iyawo”) – when he finds out Yejide poisoned her in-laws. It is why she tells Akin that “[a] bird chewed it off my head on my way home” when the latter wants to know what happened to her hair in the aftermath of Olamide’s death. It is why she attempts to terrify Funmi into submission the first time the latter comes to visit Yejide’s salon. Of course, Funmi, well versed in the Yoruba art of linguistic dueling, claims victory by subterfuge, sidestepping Yejide’s barbs so that they boomerang.

When Iya Bolu first arrives beside Yejide’s salon, she absolutely roasts her: Iya Bolu is a fat illiterate who belches between her words. If she said good morning to you, you got an accurate idea of what she had eaten for breakfast, along with a spray of spit that followed every word she spoke. Children spilled out of her salon like water from a fountain and littered the passageway that we shared. Iya Bolu was always shouting at her daughters. And the few customers she had went home with more spittle in their hair than setting lotion.

6.

In addition to language, Adebayo plumbs Nigerian history (with a Yoruba bias), real or imagined. Out come Olurohunbi, ijapa, egbere and M.K.O. Abiola.

Abiola is by now committed to collective Nigerian memory. Easy, given that every June 12, the man’s grave is now routinely pissed upon by the venal class that proved his undoing. The conflagration ignited by IBB’s annulment of those elections is what Akin and Ikenna had to pierce in their respective contexts. (Since the fateful events of those times, Nigeria’s political class has taken extreme care to nip such rare, popular articulations of Nigerianness in the bud, a nation able to define its nationhood presenting a truly terrifying anathema to the carving-up of the commonwealth).

Ijapa is an even more famous Yoruba phenomenon than Abiola, but Olurohunbi and egbere require some manner of specialist knowledge of Yoruba mythicisms. While the egbere, with its hideousness and mat and tears, is a purely mythical creature, mythicism has been ascribed to the tortoise and an everyday woman. This particular tortoise has good intentions but is impatient, while Olurohunbi, as ever, gives too much away in pursuit of happiness. Clearly then, in Adebayo’s hands, these apocryphisms function as metaphors for her principal characters.

7.

There was a time when barrenness was staple grist for Nigerian film. Those stories were essentially vindications of righteous, resigned wives who were usurped for being unable to bear fruit in a fashionably acceptable time. It was a time when it wasn’t common knowledge that a man too could be infertile, which meant no one paid any real artistic attention to the man. Pitted against the God-fearing, barren, God-trusting wife would be an upstart, unassuming at first but full of assumptions soon enough, egged on by a Patience Ozokwor of a mother-in-law. The husband would be powerless in the face of his mother’s machinations.

Stay With Me would conform to the pattern except that Yejide is no ingénue. Yes, she arouses pity for what concoctions she has ingested, what fasts she has fasted, what mountains she has climbed on account of conception, but it’s the same Yejide, who isn’t particularly religious, who poisons her in-laws out of rage, who, when pitted against the upstart, is more aggressor than aggressee.

8.

Adebayo’s prose is easy, in true adherence to the dictates of the Achebe school of fiction. It is home-spun too, or at least tries to be. This is perhaps why Diana Evans’ Guardian review describes Adebayo’s style as “a thoroughly contemporary style that is all her own,” a claim echoed on the sleeve of the Nigerian edition of Stay With Me, a claim whose echo of Dylan Thomas’ famous claims about The Palmwine Drinkard is eerily uncanny.

While Obioma is already a strong, enthusiastic stylist, Adebayo appears to still be learning the ropes. The suggestion is absent from the book sleeve but it is just this sentiment that Diana Evans prefaces her identification of Adebayo’s “thoroughly contemporary style” with.

Adebayo’s prose is even-keeled, yes, but it is low-energy, unremarkable. No passage here, no sentence, inaugurates that twinge of positive envy Longinus described ages ago. “For by some innate power,” he wrote, “the true sublime uplifts our souls; we are filled with a proud exaltation and a sense of vaunting joy, just as though we had ourselves produced what we had heard.” This “unremark” is made starker when the novel inevitably sinks, like many novels tend to do, into the Mire of Undistinguish, that middle passage where writing is less a smile and more a grunt.

“It is the children of the orange tree that cause sticks and stones to be thrown at their mother” is representative of our characterization of Adebayo’s prose. This is her approximation of the Yoruba saying “omo osan ni ko kondo ba’ya e.” She has oddly opted for a literal translation – “omo osan” is “children of the orange tree” – where a more circumspect, poetic approach might have been more amenable to the mischievous spirit and sound of the original Yoruba. It is this kind of poetic circumspection that Wole Soyinka describes when he says of his translation of D.O. Fagunwa’s Ogboju Ode Ninu Igbo Irunmale:

The pattern of choices begins quite early, right from the title in fact. Is Irunmale to be rendered literally ‘four hundred deities’ rather than in the sound and sense of ‘a thousand’ or ‘a thousand and one’?… Fagunwa’s concern is to convey the vivid sense of event, and a translator must select equivalents for mere auxiliaries where these serve the essential purpose better than the precise original.

There is bound to be some sort of naturalistic argument that the characters, by dint of being narrated in the first person, should perhaps be seen as the vessels of this novel. (If there isn’t, well, consider the following as proactive.) The writer has only selectively mediated between the naturally-occurring and the artistic: the argument will continue.

But why does anyone pick up a novel? Is it to be confronted by mundanities cloaked in the mundanities of everyday? Or is it because we recognize in the very idea of the novel the possibility of transport, the transfiguration of the everyday? Is it because we recognize in the idea of the novel a vehicle through which we might be stung out of the languor and complacency of everyday?

And perhaps we’re not even being fair to the everyday, or its so-called mundanities – shall we soak ourselves in the market, in the street, in Twitter, in Facebook and not be thrilled by the freshness of language, the creativity, through which relationships are transacted?

What excuse, then, does art have?

*********

About the Reviewer:

Kayode Faniyi is a writer and cultural critic. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Microbiology from the Obafemi Awolowo University. His work has appeared on the The Kalahari Review and Music in Africa.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions