BAKWA, Cameroun’s leading Anglophone literary magazine, is listing 100 Camerounian literature books, with the hashtag #100daysofcameroonianliterature. The program, according to the magazine’s editor Dzekashu MacViban, is meant to raise awareness on books by Cameroonian writers, to increase their visibility and make people curious about literary production in a country whose best known names appear limited to Mongo Beti and Ferdinand Oyono and, until recently, Imbolo Mbue.

Here are books in the program so far.

Day 1

Three Plays (2003) by Bate Besong. Éditions Clé.

“Long before Yaounde had its severe garbage problem, Bate Besong in Beasts of No Nation reduced the capital of Cameroon to a ‘shit’ bucket inhabited by ‘beasts’ and nightsoilmen. . . he has the rare quality of using unsettling images.”

—Nalova Lyonga.

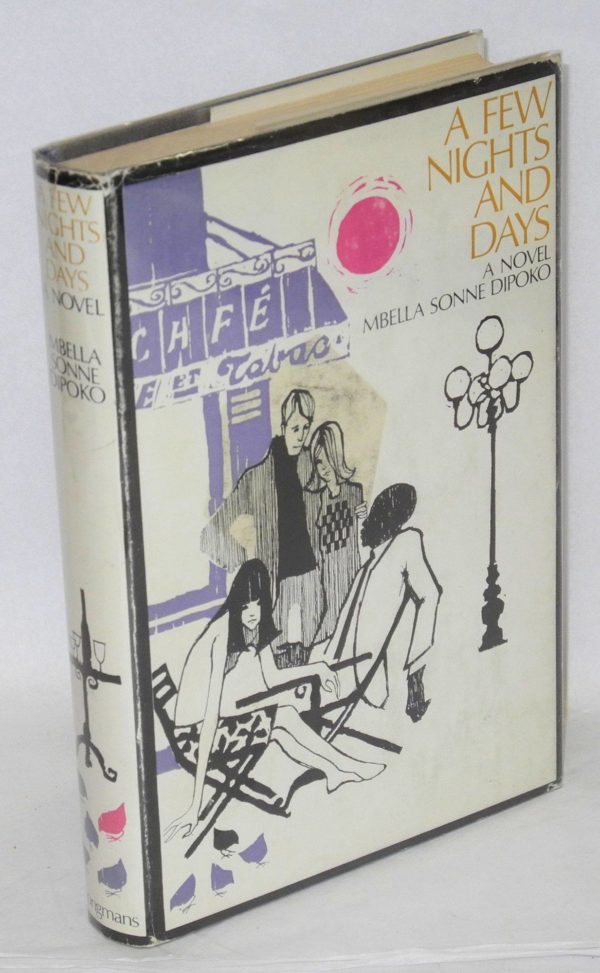

Day 2

A Few Nights and Days (1966) by Mbella Sonne Dipoko. Longmans.

Many European and American critics found it difficult to wrap their minds around the novel which departed from the standard African literary fare “about solid tribal wisdom, ghoulish rituals and the inscrutable cruelty of colonialism-not to mention the inclusion of semi-profound proverbs and the utterances of very old men with dry skin and wizened faces“ (Paul Theroux, 1966: 52). As one often quoted passage in Theroux’s review of A few nights and days states:

“No African novel has described copulation in such feminine terms as Mr. Dipoko’s. It is not only a feminine novel written by a man, it is also a novel with a country; that is, France. An African novel about France? No. A French novel about France by a man who writes like a European woman.” (p.52).

Dipoko’s next two books – especially Because of Women with its “scenes of ecstatic love-making“ (Morsberger, 1970: 353) – were alternatively panned and praised for their eroticism. The sexual undertones of Dipoko’s writings largely defined him as a writer and shaped public perception of him for the next four decades – a perception which was not too far from the truth.

(from: In Memoriam: Mbella Sonne Dipoko – The Bard Who Dared To Be Different by Dibussi Tande [Originally published in PalaPala magazine])

Day 3

The Poor Christ of Bomba (1956) by Mongo Beti

In Bomba, the girls who are being prepared for Christian marriage live together in the women’s camp. It is not clear whether the girls have to stay in the women’s camp for such long periods for the good of their souls or for the good of the mission-building program. Only gradually does it become apparent that the local churchmen have also been using the local girls for their own purpose.

Day 4

Your Name Shall be Tanga (1988) by Calixthe Beyala

Calixthe Beyala’s first two novels C’est le soleil qui m’a brûlée (The Sun Hath Looked Upon Me, 1987) and Tu t’apelleras Tanga (Your Name Shall be Tanga, 1988) have as their protagonists young African women who are oppressed and exploited by their mothers as well as by men. In Tanga’s case, a brief sexual relationship with a white woman in prison probably represents the first lesbian scene ever published in a novel by an African woman. Femme nue, femme noir (Naked Woman Black Woman, 2003) is also remarkable in its explicitly erotic style, the main character enjoying her sexuality in a way that elevates freedom from male sexual domination to a political strategy for African women.

—Marc Epprecht, Routledge International Encyclopedia of Queer Culture, 2006.

Day 5

Dog Days (2006) by Patrice Nganang [Temps de chien (1999)]

“I am a dog,” the narrator of Patrice Nganang’s novel plainly informs us. As such, he has learned not to expect too much from life. He can, however, observe the life around him—in his case the impoverished but dynamic Cameroon of the early 1990s, a time known as les années de braise (the smoldering years). When he isn’t limited by the length of his master’s leash, the perceptive, even ironic, Mboudjak wanders the streets of Yaounde, a capital city caught in the throes of social and political change. Only partly understanding the words spoken around him (the other dogs are as unreliable as the humans), Mboudjak relates an experience that not only evokes the wildly diverse language of the streets—a heady brew of French, Pidgin English, the indigenous Medumba, and the urban slang Camfranglais—but also reflects the elusiveness of meaning in politically uncertain times. Mboudjak is not alone in his confusion or in his hardship. The blows he receives from humans and the mocking laughter of other dogs are indicative of a larger pattern of abuse that indicts the ruling regime.

Despite its unflinching depiction of a seething, turbulent society, Dog Days is not a somber story; it is propelled by the humor that is Mboudjak’s greatest survival tool, and even by a certain optimism. In the vibrantly chaotic marketplaces, in the bustling energy of Massa Yo’s bar, and in the escalating political demonstrations, a brighter future for Cameroon can be glimpsed. This story told by a canine everyman offers something for any reader interested in freedom withheld and the early stirrings that will someday win it back.

—The University of Virginia Press.

Day 6

The Crown of Thorns (1993) by Linus Asong. Patron Publishing House.

Chief Nchindia held the Elders of his Council in total contempt, inwardly vowing to disagree with them at every point where disagreement was possible. What starts like a big joke develops into grim tragedy: the statue of the god of Nkokonoko Small Monje is discovered to have been stolen and sold to a white man! The tradition demands instant execution of the culprits. Was their Chief involved in the theft? What was worse, the crime or the punishment?

Day 7

Across the Mongolo (2004) by John Nkemngong Nkengasong. Spectrum Books Limited.

In this first novel, Nkengasong handles a number of issues, to wit, the situation of a marginalized fraction of a country which unsuspectingly surrenders its freedom, traditions and overall way of life to the oppressor brother. (The major character’s travails come about largely because he is from this oppressed minority). At another level, the novelist makes a statement on the world of the university, a world of its own but which is also an eloquent statement on the state of two uneasy bedfellows unfortunately yoked together by the ironies of history. The place of the tribe in the life of the individual today and the idea of growth, awareness and disillusionment constitute some of the major concerns in the novel.

Ngwe is presented as an extremely sensitive individual who goes through harrowing experiences which unhinge his mind and leave him drifting like a lunatic, full of bitterness against the system in which he lives and operates. The story ends with the welcome announcement that Ngwe’s ordeal was timely preparing him for the messianic role cut out for him by the gods (that of liberating his people from slavery in a faraway land).

—Eunice Ngongkum.

Day 8

Dark Heart of the Night (2010) by Leonora Miano [L’Intérieur de la nuit, Plon, 2005]

Miano’s 2005 novel L’intérieur de la nuit (translated by Tamsin Black as In the Dark Heart of the Night) tells the story of a woman who returns from France to her fictional African village to visit her ill mother. Ostracised by the villagers as a “foreigner” and for failing to bring presents, she decides to leave, but on the eve of her departure a guerrilla group raids her village and uses some twisted form of Pan-Africanism as a way of subjugating the villagers. Miano disliked this English translation, as did many of my French-speaking friends who had read the original novel, and their disapproval compelled me to buy it. I was curious to know just how bad the translation was – and as it turned out, I enjoyed it. If In the Dark Heart of the Night is a bad translation, I would like to read the good translations of all her other work because this Cameroon-born Afro-pean writer, now based in France, is brilliant!

—Zukiswa Wanner, The Guardian.

Day 9

No Turning Back: Poems of Freedom 1990 – 1993 (2007) by Dibussi Tande. Langaa RPCIG.

Though Tande is a poet with a view, a global view, he is at his best when he casts his sharp poetic eye on Africa in general and Cameroon, in particular, and vocalizes the anguish of his native oppression. The poet laments that the birth pangs of freedom of the 1990s led to tribulation, which morphed into the death throes of youthful idealism. The poet metaphorically shakes his fists at the rebirth of tyranny in the aftermath of Africa¹s post independence wind of change in the 1990s.

—Lyombe Eko.

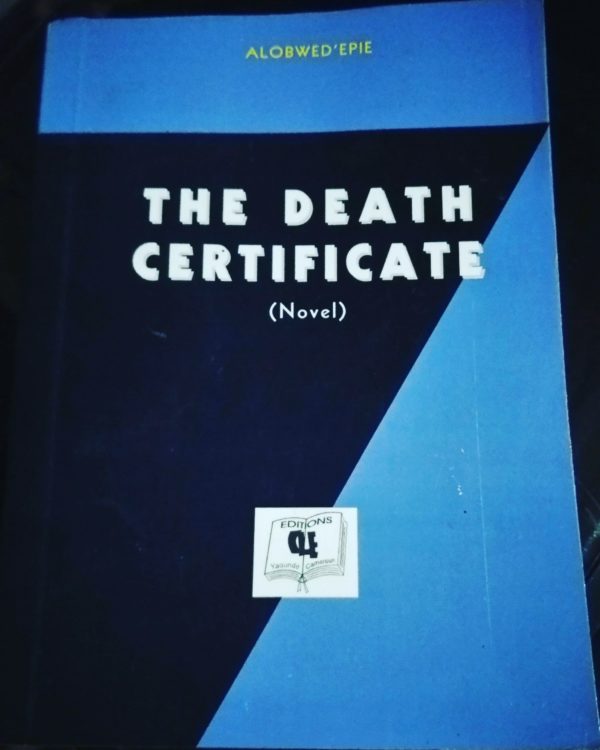

Day 10

The Death Certificate (2004) by Alobwed’Epie. Éditions Clé.

“His is the middle style, neither high nor low; a vast, sprawling, almost limitless universe which exhibits throughout an organic unity of style. . . Mongo Meka is a paradigmatic and prototypical case of the thieving Zoetelle elite of the First and Second Province of Alobwed’Epie’s fictional Ewawa. He has embezzled 550 billion francs cfa from the Central Treasury in Dande, Zoetelle; invested 100 billion francs cfa in Kabon and Ewawa, and subsequently looted and deposited 350 billion francs cfa into Antoinette’s account in Lyons, Paris. This, Mongo Meka did with the belief that should the Ewawa government catch up with him, the money would be safe in his French wife’s account.”

Bate Besong, Prodigals of Dangerous Ambition.

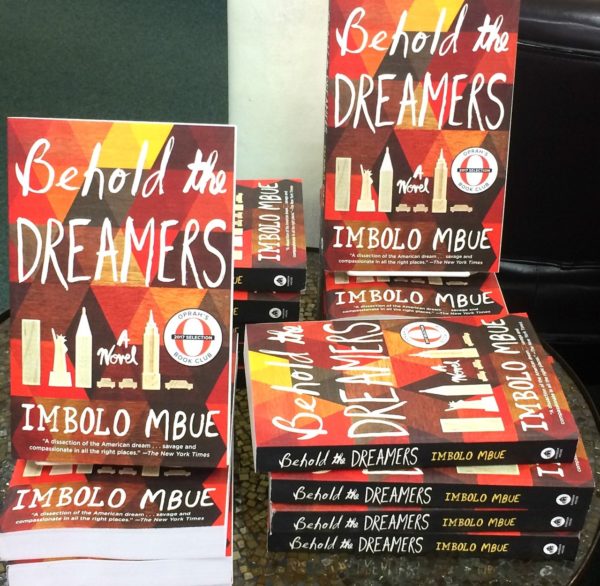

Day 11

Behold the Dreamers (2016 ) by Imbolo Mbue.

The years 2007-9 were bad ones for America. The housing bubble burst, the auto industry was in free fall, unemployment rose as high as 10 percent, and Wall Street was at the edge of an abyss.

It’s just before this tumult that Jende Jonga, an immigrant from Cameroon and one of the central characters in Imbolo Mbue’s debut novel, Behold the Dreamers, arrives in New York with a visitor’s visa and the hope that somehow he might transform his temporary status with a green card.

—Christina Henriquez, The New York Times.

Day 12

This Is Bonamoussadi (2008) by Oscar Labang. Miraclaire Publishing.

This Is Bonamoussadi gives insight into the imagination of a remarkably sensitive poet. This epic-scale poem constitutes a chaos of ideas in a synthetic consciousness; a network of disconnected sensibilities that indict the triumph of evil and greed, bad leadership as well as hypocrisy and fraud not only in the filthy cityscape of its title but in Cameroon and Africa as a whole. Stylistically it reveals a radical experimentation in form, including a breakdown in generic distinction – poetry and prose and poetry and drama. In short it is a postmodernist celebration of the liberation of genre.

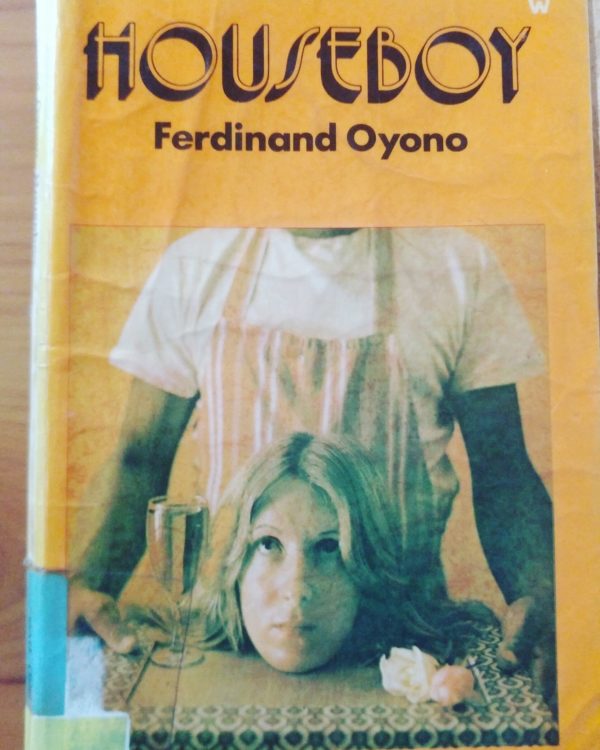

Day 13

Houseboy (1966) by Ferdinand Oyono. African Writers Series.

Ferdinand Oyono begins his haunting tragedy at the end of a Cameroonian houseboy’s life. “Brother, what are we,” Toundi Onduo asks as he enjoys his last arki, only minutes before his death, “what are we blackmen who are called French?” It is a question that echoes throughout the novel. Houseboy, the story of an African man who from a young age served white colonizers in his native Cameroun, depicts the plight of Africans who suffered brutality and subjugation under the boot of colonial authority. It offers a glimpse into the life of an articulate African, Toundi Onduo, who was at first intoxicated by the offerings of the French, and determined to assimilate into their culture, but later realized the hypocrisy of European culture and despised its rule of his people.

—Graham T Baden.

Day 14

Lake God and Other Plays (1999) by Bole Butake. Éditions Clé.

Bole Butake’s three plays Lake God (1986), The Survivors (1989), and And Palm Wine Will Flow (1990) were all written against the backdrop of rapacious and inhumane oppressors of the seemingly silent and marginalized masses.

One question which comes up several times in these plays is: “Where are the men?” The men have either been exiled, incarcerated, or totally emasculated. In And Palm Wine Will Flow, the male sacred society, the Kibarako, is stripped of its judicial powers, unmasked, and sent into exile.

—Emmanuel N. Ngwang.

Day 15

The White Man of God (1980) by Kenjo Jumbam. African Writers Series.

The work has a comic flavour and is narrated with disarming candour, although it is not, finally, funny — many incidents have biting satirical undertones or leave a feeling of desolate sadness.

Far more serious than this accusation of cultural apostasy, however, is Yaya’s recognition of the difference between the humaneness of the indigenous traditions and the harshness of Christianity preached by “Fadda”, (i.e. father, the highest ranking local missionary). Like most of his associates, he likes texts such as “but whoever refuses to believe is condemned already.” Yaya calls it a “snare” and says: “Your new religion has impossible laws and its God is cruel. It is only the God of the white man who puts a man in hell-fire and lets him burn there like wood. . . for ever and ever while God never lifts up an eye of mercy to him. What cruelty to imagine of a God!”

—Annie Gagiano.

Day 16

It Shall Be of Jasper and Coral (2000) and Love-across-a-Hundred-Lives (2000) by Werewere Liking. University of Virginia Press. [originally published in 1983 in French]

The West African writer, painter, playwright, and director Werewere Liking is considered one of the best literary interpreters of the postcolonial condition in Africa. Her first work to be translated into English, these two novels spare nothing in their satirical portraits of the patriarchal view of African society as they experiment radically with the novel form. It Shall Be of Jasper and Coral (Journal of a Misovire), subtitled A Song-Novel, introduces the “misovire”―literally defined as a man-hater but seen by Liking as the figure of a time when gender differentiation will be irrelevant to discovering the fullness of what it means to be human. The misovire recounts the story of the inhabitants of Lunaï, a squalid fictional village in Africa. The novel’s action occurs on two levels, as the misovire contemplates writing a journal, and through that heralds the creation of a new race.

In Love-across-a-Hundred-Lives, the narrator tells the story of Lem, her brother, who is preparing to hang himself when his grandmother Madjo appears. He secretly expects her to dissuade him from suicide, but instead she encourages him, urging him to make his final action a success that will make up for all his earlier failures. As he continues to knot the rope that will be his noose, Madjo tells Lem stories of their ancestors.

Day 17

Three Suitors . . . One Husband (1968) by Guillaume Oyono-Mbia. Methuen. [Originally published as Trois prétendants . . . un mari, 1964].

Oyônô-Mbia introduces us to an African milieu of strong traditions. He portrays the plight of African women, and especially young ones, who have been educated but return to their village to be sold, according to ancient custom, to the highest bidder. The character of Juliette stands up against centuries-old custom and defies her destiny through cunning and craft. Hardly has she arrived home from her school in Dibambaa—a play on Libamba, the town where Oyônô-Mbia was educated—when she learns that she has been promised, in exchange for 100,000 francs, to Ndi, a local farmer of her age. She also finds out that Mbia, a civil servant from town, who is of her parents generation, is expected that very afternoon.

—Hélène Sanko.

Follow #100daysofcameroonianliterature on BAKWA’s Facebook page, and on their Twitter and Instagram.

Samuel Dzombo December 22, 2017 05:29

keep it up Bakwa. Keep on enriching the African literary scene.