In 2012, the Centre for African Cultural Excellence (CACE) based in Kampala, Uganda, launched Writivism — an initiative that identifies, mentors and promotes emerging Africa-based writers, and hosts an annual literary festival in Kampala. In 2017, Writivism celebrated its fifth anniversary and to celebrate this milestone, the initiative, in partnership with the University of Bristol, is publishing an anniversary anthology of short fiction titled Odokonyero: A Writivism Anthology of Short Fiction by Emerging Ugandan Writers. The project involved creative writing workshops, which were held in the summer of 2017 in Kampala and Gulu as the basis from which the anthology was developed. The special anthology contains writing by 18 young Ugandan authors and this is “My Name is Ojwiny,” the entry by George Ocen.

***

The waiting lobby stretches on endlessly between duty free shops: a bookshop, a craft shop with all sorts of Ugandan artefacts, garments, a sweets shop, perfume and make up. The endless shops are broken by boarding gates with metallic chairs and a few bored looking people waiting. The mix of cologne and other toxic sprays is cracking my nose. Someone must have gone to town on samples in the perfume shop. White people are way too many here; this is supposed to be an African airport. We are inside Entebbe International Airport. The two officers assigned to me are following me more closely than my own pair of buttocks, their eyes glued to every movement of my limbs. Where would I run to? People look at my hands which I hold together in front of me. The bastards had the decency to cover the handcuffs with a cloth so people don’t see them. I don’t care. We reach Gate 005 and one of the goons pulls my shoulder to indicate that I sit down. They help me sit on the metallic chair and they sit on either side. I look around; the racial mix, the swagger everybody walks with, the air of wealth and aura of importance around everyone is nothing like the simplicity of the folks back home at Teso Bar. I cannot turn around and strike a conversation, everybody seems to be minding their own business.

A young man in faded jeans, with a mound of hair on his head pressed down in the middle by the weight of his hefty headphones nods ceaselessly. He is the only one I think I might have a rapport with. Fattened ladies wrapped in lesos try to catch an early morning’s sleep, bald headed men in casual clothes look too serious behind their spectacles. I let them catch me staring. I do not care. Then it hits me. I am leaving. I am leaving everything I’ve known all of my life — the people the food, the landscape, my language, the women and most of all the bars and brew behind. For the first time I am really frightened. How did it come to this? It is a long story, the story of my life.

I had to trek for long to look for a new joint because Jei had smoked out all the ones I’d been to in the past month. This day if he showed his brown head up I swore would not have money for two. I drink as much as ten amateurs in one night. And he demolishes liquor of a quantity nearly my own. I hated to take care of this thirty-year old dependent. Even claiming to be my son just because he is coloured. The neighbourhoods had repeatedly declared that I was the father of every thick-haired-coloured toddler sired in their midst. And they were numerous. I headed to Rachel’s, a newly opened bar across the swamp separating my suburb, Teso Bar, and Lira Town.

The bar was decent. New as it was, the large crowd surprised me. I saw the high table, a skinny mahogany stool that stood tallest. Teso Bar locals loved drinking competitions. Today day there was even an umpire.

I watched as the jars were filled up and the umpire counted to three. The two competitors swigged their respective jars, the voluminous liquor gushing down their throats without any pause. The taller one took two long minutes to down his half-litre of gin, microseconds ahead of his stout competitor. The target was five jars. The talker won and he swiped the 50 shillings prize into his breast pocket as his competitor threw up on the floor. I puffed away my disappointment with a joint of marijuana. It was much better than the gamers.

‘Ojwiny!’ someone called out to me. That was my name in these parts given to me at a beer party. Grand evenings in which we sat on foldable timber chairs around a pot of abwa, mild millet brew, sucking at the end of straws made from hollow branches of ceke. Here we caught up on local news and gossip. Nearly every week another story about me and some woman came up. My fellow drunkards laughed and called me Ojwiny. Ojwiny is a tiny wild bird with a notably long tail. Its male never perches in a single nest—it circles the woodlands occasionally dropping by a nest to woo and mate. It is rumoured that its sexual prowess is such that it mates with any bird.

‘Ojwiny, that kid has won three games in a row. And he is still going.’ I recognized Kazungu, the little man with a hooked nose. He did not wait for my reply but hurled me out of my stool. I hesitated while he got behind me. He gently pushed me forward with his palms chanting, ‘Howard Ho …’ rhythmically with a staccato pause at every syllable. Being of small stature, he looked like a dung beetle with me as its load. The whole crowd joined in the chant. The uproar was compelling, and so I moved. At the high table I was curious about this new challenger to my drinking record. Lo and behold it was my alleged son. This David was surely going to fall on Goliath’s sword. The judge signalled, and we started. I whooped him in four straight sets. The roof began to spin. The umpire held up two fingers asking whether I was good to go for another round. I nodded. On the second jar I heard a strange sound.

‘Pii, pii, pii. Poo poo poo!’ Soon blue and red lights were dancing on the high table. Everybody took off in flight. A brown hand ripped open the zipper on my breast pocket and swiftly made away with my prize money. ‘Thank you, daddy,’ shouted the fleeting voice, cynically. I steadied myself, but my legs were jittery. I hauled myself over the counter. It was clear to me that the police had raided the bar. Instead of landing on the opposite side I crashed into a dozen enamel jars. My face washed in the lira-lira as it soaked my face. I licked the crispy waste before the lights faded, and I felt the click of metal over my wrists.

Kok!! Kok!!! Kok!!! I heard my insides make that noise. I opened my eyes, and I was on a cold courtroom floor. My view was blurred, an ugly black officer with a lizard’s head grinned from ear to ear as he prodded my belly with the tip of his leather gumboot.

‘Wake up sir,’ he sneered from between his gritted teeth. He administered a final kick and told me to stand up because court was going into session. I staggered to my feet in honour of the judge who was making entry. I could not quite steady myself. An excruciating tinge ran through my head, and I closed my eyes. ‘Ouch!’ I shrieked out before receiving a straight slap to shut me up. I kept wondering why the headache was so horrendous. I realised Lira-lira and marijuana were duelling inside my head. I had never had such agonizing aches before; I guess it was because I had not added on khat to bring the other two into tandem. Perhaps it was the rubber carpet on the floor of the police truck. Those officers had violently pressed my head against it with the giant treads of their jungle boots. My temple had gullies like a dirt road treaded by a Land Rover truck on a rainy day. But I remembered I had not resisted. Why had they kept stomping at me? Was I a sack of starchy tubers that needed fastening? Indeed no substance however strong had ever made me reel with pain in the morning. This could not be a hangover. It had to be the police boots.

How else would they show their superiority? I wished it were the colonial days. I would have squeezed their throats. I would have been the one with pliers tightly holding their lice infested balls. I would have knocked their thumb-piano-wire teeth inwards. A smile crawled across my face and it was so sweet that it relieved the headache a bit. Suddenly my insides sounded again, kok. This time the kick landed on my derriere. The judge had called, and I had been too absentminded to walk to the docks.

In the docks I lifted my head to look at my condemner for the first time. Sweet relief, it was a white man just like myself. I gloated with a sense of victory over my sooty black accusers. The adjudicator was white, and I knew I would be set free. A young man stood and read out something that I cannot recall.

‘Where do you come from?’ the judge’s roar tore through the packed courtroom.

‘Uganda’ I replied. The judge shifted uneasily in his seat.

‘I mean, which country, what is your nationality!’ I had never heard so much rudeness in one voice as I then heard in that judge’s. I lifted my eyes and his bloodshot ones stared right into mine. One fact gave me courage. Whatever he smoked I had smoked before. I recall a day when my eyes had been exactly crimson as his were that day. I could not recall what I had taken. And so I replied confidently because we had more than just skin colour in common. ‘Ugandan my Lord, I am Ugandan.’ At this point he rubbed his nose, and it flipped from left to right like a giant windsock. Without him asking again I said, ‘I am Ugandan, my Lord.’ His bottom seemed hard knocked by the cushioned mahogany seat. His hands clasped as though they were restraining each other from flying at me. Noticing his rage, the whole court room went deathly quiet. I read his mind. He perceived me a traitor; a Judas to the race! In that immediate postcolonial period where only noble professions were still for white folks, where Africans were unable to judge their own cases, for instance, how could I have been arrested in the middle of the night, even socializing with the most despised and worthless of Uganda? Incarcerated by native khaki-short wearing policemen? How could I be brought to the docks sharing handcuffs with a juvenile delinquent? He seemed to be wondering why I was not in high life with the rest of the white folks.

He fumed and exploded. ‘By the laws of Uganda, you are guilty of being idle and disorderly. You are hereby sentenced to three weeks in prison, with corporal punishment.’

With a nod I thanked him for the leniency. It was my first conviction. The thought of corporal punishment reminded me of some Acoli people who caught me with their girl. Yet before I could relive those whips, a rugged policeman clasped my hands with cuffs rustier than the first. He shoved me and as I staggered forward he straightened me with another firm kick on my buttocks. A sinister sound of elation rising in a crescendo filled the room. It had to be those bloody Africans in pews celebrating the plight of a white man or amazed by it.

Prisons are a good place to be. It fills you with worth because for once you are in the shoes of Jesus Christ on his way to Golgotha. We were roughly pushed out of the police truck. Unable to balance myself because I was a novice with handcuffs, I dropped to the ground like a sack of yams. The police should have used tipper trucks and poured us out like a trip of building sand. Their pretence in pickup trucks exasperated me.

We were relieved to have new masters. In appearance the prison warders seemed less callous. I smiled lightly and to no one in particular. A large man at the end of the straight pack looked at me fiendishly. I nodded at him. He kept his diabolic face fixed on me. I freaked and frowned. He nodded and coldly turned his gaze. That should have told me that I finally had the right face on. The tin gates very noisily rattled as a warder worked a lock on its twin shutters. The lock was as stubborn as one of a very old and forgotten museum in virgin jungle unknown to man. The shutters flew open to separate the letters LUZ and IRA inscribed on each of them.

‘Luzira,’ I whispered to a youngster next to me. ‘But this is where they bring murderers.’

‘It’s the other wing’ he pointed with a knowing that showed that this was not his first trip to that place.

A file of warders marched in dressed in a colour somewhere between green and yellow. They caressed the bulged tips of their batons, looking at me with amazement. The warder that came in the truck with us unwrapped a paper crease by crease. He spoke to a potbellied warder. We overheard something about a magistrate, a white man. Then he clenched his fist and punched. The pot-bellied warder bit his lower lip and looked my direction with a murderous leer.

‘What are you doing here mzungu?’ hissed my neighbour.

‘Quiet!’ a small warder angrily yelled at him. I pondered how I could fling that son of a bitch with one finger. He walked over and ordered the man who had spoken to me to open his mouth. He slapped him hard on the left and right cheeks. I thought it was his punishment but suddenly all of us were subjected to the same battery. Their hands ransacked our pockets. Our belts and laces were ripped and cast away.

Shortly we were ordered on our feet and locked away in cells. Twelve of us in a two by two cubicle. We could not tell what hour of the day it was. A warder strode along the corridor clicking his baton over the railings of our cells.

He saw me and said, ‘You get out.’ I realized that I was in the last cell at the head of the queue. He had picked out fifteen other people. He pushed us onto a concrete platform. Our feet were fastened and hands stepped on.

‘It is time for your dinner.’ A group of three officers strode in. We were pounded with batons on all parts of our bodies. This went on for close to five minutes but felt like an hour. I screamed for twenty minutes after they were done. Two officers dragged me to the cell since my limbs were wobbly. My friends were perplexed when I was dropped back onto the floor. I passed out into a long painful sleep.

Three days later, bells rung as usual to herald the dawn. In that dungeon we told time through sounds. Not a single ray of sunshine broke through. The cells were opened, and we stepped out. A Leyland truck was waiting. We boarded it. Each of us was given either a shovel, a hoe or an axe. A warder handed me a pick-axe and we were shown a footpath. The savannah pastures were getting higher as we trudged on. The vegetation suddenly vanished, and in front of us stood a bare rock staring at us. I turned around and realized everyone around me had a pickaxe as well.

‘Get on with work,’ a mean faced officer said staring at me. I pulled the axe over my shoulders. I straightened it, held it over my head and I brought it crushing onto the granite. Its metallic handle painfully twisted inside my palms. I lost grip as it flew up and administered a hard bang to the backside of that officer’s head. He charged at me and was about to kick me when his colleague restrained him. I looked at my palms, and they were bloodied. I decided that I would take none of their nonsense. I strode and sat myself under a tall eucalyptus. The warders were perturbed.

‘Get back here, you guinea pig.’

‘Swing and catch me here, bloody ape’ I mumbled inaudibly.

‘Didn’t you hear me?’

‘Of course I heard you, monkey.’

He hurriedly approached me wielding his baton. I took that moment to arm myself with a branch of a nearby opobo tree. He drew first as he hit my hip. I responded with a lash at his neck. Followed by another one and another one. I saw his very black neck turn red. I shifted my target to his back just before a corporal sting bruised my own back. Half a dozen prison warders descended on me from all sides and beat me to pulp. At least I was getting my due sentence, corporal punishment. I loathed hard labour. And those chaps had learnt their lesson. I missed my dinner that evening. I guess they perceived I had had enough for the day.

My fellow prisoners were thrown back in the cell in the evening. Their eyes were literally hanging in their sockets. They arched and crouched in their corners breathing heavily. They were haggard and looked worse than tropical monkeys trapped in snow.

‘Hoe,’ one said to me. ‘It is better to get beaten, than to beat a rock.’ He showed me his scaled palms and continued. ‘I cannot even wipe my own ass after shitting, unless I want to die of pain from my palms meanwhile leaving my ass red.’ I seriously felt sorry for him though he was Acoli.

Florence was a chubby Acoli belle. She was a little overweight for her age. And yet she was tall and had a cute smile. When she passed my kiosk, she flashed smiles at me. She knew I was old enough to be her father. She did not care. I knew the same too. I cared even less than she did. I beckoned, and she came close to me. Her nails were neatly filed, her skin was smooth and taunting. So I touched her arm, and my fingers slid over. It was not as rough as some African bodies that blister palms. She spoke with a stupid lisp and her high-pitched local voice was something I longed to hear tuned to the melodious mutterings of sexual pleasure. I longed to savour all the sweetness in her.

‘Florence dear, you are an angel,’ I teased her. She swung her fleshy body and twisted her neck diagonally to look at me. ‘O really, thtop joking, mthungu?’ Her pony-tail stood short like my puny prod when not yet awakened, so short. Her front teeth clicked, and she looked like a rodent in the presence of grain. I knew she wanted it. I provocatively struck her teenage thigh. It trembled for seconds. I led her by hand into my house. ‘Hoe thtop it’ she laboured to resist. I was halfway demented; my persistence became spirited. Her skirt was cast on the floor. I pushed the door and window closed with one movement. I was about to launch at her when there was violent knocking on the door. I had to act quickly. I picked up a Bible. Dressed her up and order her to kneel.

‘Howard what are you doing.’ I could hear other voices. Soon it was the roar of a crowd. The door flipped open and I was pulled out foot first. I fell on the brown sand, Bible clutched in hand.

‘You will not fool us, why behind closed doors with that little girl,’ one man shouted

‘This confused Mzungu should just go back to London,’ another jeered.

Until that day at the rocks I had thought those were the hardest canes I would ever get. Yet then I knew that corporal punishment at the hands of the state is superior to untrained whipping by some drunken Acoli lads and frail elders.

I fell asleep with that story in mind. All of a sudden it was bright, and the sun was brilliant. I was alone brushing my canoe for a later excursion into the sea. I turned around and Florence was standing. The same old meticulous body. This time she had wrapped a light scarf around her body. I was delighted. I held her in my arms. My penile inflation was granite hard. I launched into her, so deeply she fell back in satisfaction. O lovely Florence. How I missed you.

My eyes opened, and a smelly foot hung over my head close to my nose. Another guy with an open mouth was grunting close to me. There was both soft and loud snoring. I alone was awake. I moved a little and felt the wetness around my genitals. I had just had a wet dream. I smiled at myself and I lay my head to try and sleep again.

The day after the gates of Erute closed behind me the small officer told me I was free to go. I had only been inside one week and three days. My good conduct had led to a shorter sentence. Based on my own assessment of my conduct, I felt I deserved to have mine prolonged. It felt good to be free again. I kicked my feet and waved at the officers on the watchtower. They smiled back. I flipped both middle fingers over my head and did not look at them. I skidded about like a little goat, reminiscent of Teso Bar and gladdened by the thought I was only hours away from arriving at my beloved when a Land Rover truck stopped by. I moved aside for I deemed it to be making way into the prison. The khaki suited car driver waved at me though. He signalled me to get into the car. Two people appeared from behind me and led me to the backseat. They sat me in between themselves. Both brought out pistols, and began to fear for my life. Soon the car screeched off to some direction that fright could not permit me to get right. It swerved and latched to a stop at building outside which the hexa-striped black-yellow-red flag was flying on a skinny pole. The crested crane spangled at its centre seemed my only friend then. The officers held both my arms and dragged me past a demure lady at a typewriter who paused and glanced me over her gold rimmed glasses. I stared into her eyes and they were expressionless. We did not stop to honour the greeting of two suited gentleman in sleek black shoes. I was taken into a small dark room with a single tin table. There were matching chairs scattered around the room. One of my escorts punched at the wall and yellow light flooded the room. A pack of old newspapers littered the table

‘Why am I here?’ I asked. The man at the light switch looked at me like I had broken a taboo. His colleague placed a finger over his mouth.

‘I deserve to know,’ I raised my voice. ‘Will you smelly skunks tell me what the hell …’ A door cracked open from in front of me and the magistrate appeared. Behind him were other men. The sixth man in the file had a bulge on his forehead. I recalled him immediately. I never got to know the rock I had thrown had caused such damage. Here was good old Minds, my Rector, carrying a mound at his forehead. I smiled slyly. The men were seated around the table with me. The magistrate turned the papers on the table. I recalled he was the one that sentenced me to jail. He must be the one that got me out too.

‘Howard Hoe,’ he cleared his throat. ‘You have ashamed your race. You are making the Africans think that they are equal or better than us.’ He held a paper to my face, it was dated 25th November 1954 and the headline was ‘Problem Mzungu Incarcerated.’ ‘All your escapades are documented, and it is like filthy ointment to our repute.’ He looked around the room. ‘We are educators held at high regard by the whole nation.’

‘We do what they have failed to do even though they claim Uhuru,’ another man chided.

‘My child,’ the Rector came in. ‘Your fate is sealed. We shall clandestinely deport you.’ They all rose up and left by the small door through which they came. The magistrate gave my captors a quizzical look and both nodded reassuringly. And so I was driven into an international airport.

As I lie on the waiting chair a voice suddenly breaks in the publicaddress overhead. ‘Flight 107 to Glasgow boarding right now at gate 005.’ My captors rise to their feet. I look at the clock above and it is 6 a.m. I do the same and clutch my rucksack.

Thoughts of the land I am leaving flood my mind. My lips start watering for boyo and amalakwang, the green-leaf vegetables mashed in groundnut paste. Now that I know the destination is Scotland, where will I find these delicacies? Will I ever appreciate European humour. What do they have to joke about? I love it when Okello Opok daily tells as about the conflicts in his polygamous household. How Ranga the security guard rues his decision to be that? For all women despise him.

Thinking of my white captors, I recall my father who cast me away in a monastery and called me a bastard. I recall the monastery throwing me out. The five white families that took me in doing the same one after another and labelling me ‘an impossible child.’ Lira is the land of my birth. The community was ever so receptive. I am a Ugandan and nothing else. I am Lango by tribe. And my name is Ojwiny. I am no different just because I am white. A citizen cannot be deported. I am going nowhere. Even if it means making a scene. I bang my chest and yell.

‘An abedo Ojwiny!’ I realize that I have not had any alcohol since they took me. The reality of prolonged sobriety hits me hard. I am never going to take lira-lira ever again. That fact is hard to swallow. I scream at the top of my voice, ‘An abedo Ojwiny!’

They gesture me forward. I am going nowhere. Let us see who will look foolish.

‘British Airways 005 boarding now at gate 005. Last call!’ The pair is uneasy. They are more panicky than a man with a red ant trapped in his underwear. I respond with a leer and fall back to my seat. Before I make contact with the chair they intercept my fall and haul me forward. I refuse to be carried. I refuse to move. All they can do is crouch to the floor and push my feet one at a time. Each taking care of one foot. Like an infant pressing their first steps. I wade on in gay abandon. I feel like a tortoise; the two undertake this duty so religiously that I am convinced their life depends on it. So resolutely do the white folks of Uganda abhor my presence. They are spewing me out but let me do the best in my power for now. The rest of the waiting people are watching dumbstruck. My face is expressionless. Deep down I know I have never enjoyed limelight like this before. Do we make it to the craft on time? Ask my escorts when you meet them, namely Ant and Dec.

**********

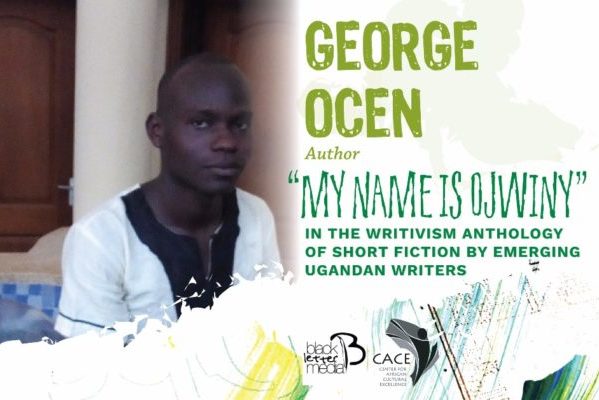

About the Author:

George Ocen has been achieving recognition for his writing from an early age. He was first runner-up in the East African Students Essay Competition in 2009 and winner of the inaugural Makerere Law Society Legal Writing Contest in 2015. He currently contributes to Makerere Law Journal and has featured at Kelele Poetry—Makerere University’s regular poetry night.

Angulu April 09, 2018 17:19

Although Ojwiny is seemingly reckless with life, I could not help falling in love with his many antics. A nice and captivating piece to read. An interesting immersion into the post colonial Uganda.