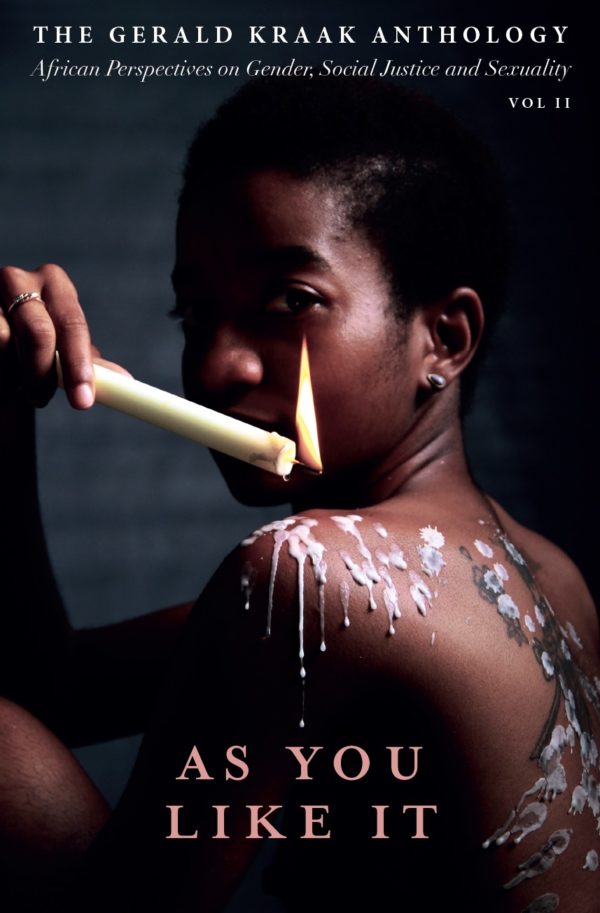

The following photo essay—“Your Kink Is Not My Kink: African Queer Women and Gender Non-Conforming Persons Find Sexual Freedom in Bondage,” by Siphumeze Khundayi and Tiffany Mugo—is an exclusive republication from As You Like It, the 2018 Gerald Kraak Award anthology (pages 136-142).

*

African cultures have long celebrated sexuality, with a history filled with customs and traditions dedicated to pleasure, sexual satisfaction and sex being seen as a social good. However, the moral frameworks of religions such as Christianity and Islam as well as notions of nationalism have in many cases submerged indigenous practices aimed at honouring and celebrating sex. There has become a serious disconnect in how we engage with ideas of sex and sexuality framing ideas around morality and warning signs about the impending doom that comes with seeing people naked.

However, issues of pleasure and bodily autonomy are again beginning to take centre stage. This is evident in the increasing number of public platforms and initiatives dealing with women’s sexual agency. For example, platforms such as Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women and The Spread Podcast centralise pleasure as a principle. The focus on African pleasure is not limited to the online space. Works like Pussy Print, by Lady Skollie, who is a feminist artist and activist from South Africa, and the Safe Sex and Pleasure (#PleaseHer) workshops by HOLAAfrica! also tackle what gets people off and what it means to control your body in wildly different ways.

It is no surprise then that new conversations about Kink are thriving on the continent – led by an unapologetic generation of queer black women. Indeed, there is an active Bondage Discipline/Dominance Sadism/Submission Masochism (BDSM) scene that is a site of pleasure, activism and academic enquiry for a queer community coming into its own in a context characterised both by state repression and pockets of social openness.

Over the past couple of years Siphemeze Khundayi, the co-creator of this piece, and I have had an increasing personal and professional interest in kink. It all begun shortly after an ‘Erotica Justice’ dialogue, which was held under the banner of HOLAAfrica, a sex positive organisation we founded. The space was created to look at how the revolution could be taken out of streets and put in the sheets. The dialogue used the starting point that sex is an important part of bodily autonomy, so people spoke about the kind of sex they were having – the good, the bad, the problematic and the mundane. At one point Tshegofatso, who had long been an online fave, held

the floor and spoke about how BDSM was based on consent, how it needed a constant discussion of wants, needs and desires. To understand your partner/s and their engagement with you and your body.

The room lost its collective mess.

‘No way!’ They cried. ‘Kink is privileged sex!’ they exclaimed.

‘These are things for the middle class/white people.’ ‘Where is the feminism and autonomy in kink?’

By the end of the conversation we were intrigued by this sexual practice that seemed to be a delicious dichotomy. We also wanted to know why the very notion of kink had been rejected by most of the people in the room. We wanted to know what we could learn from this sexual practice that was often ignored in other sexual practices. We wanted to know why there was so much leather involved and was it practical with the amount of sweating that happens when you have sex.

But the main question was: should we try kink?

And so we began to have conversations, develop think pieces, gather the observations of friends, practiced and allowed ourselves to be taught how to kneel and submit over WhatsApp and during dinner parties. We sought relationship advice based on bondage. All of this began to form a core part of the work of HOLAAfrica with photo shoots, posts on our site and even our #PleaseHer safe sex and pleasure manual which archived all of this knowledge. This essay is part of that wet and wild journey to understanding something outside our initial comfort zones. This research was one of the first steps down the rabbit hole. Within this project we reached out to some of the kinksters we had met since embarking on this journey.

Siphumeze drew from the archive of photos she had taken of various queer women. The work sought to add to the increasingly changing conversation within the Sexual Reproductive Health Rights narrative, moving the conversation away from more traditional notions of HIV/AIDS, Female Genital Mutilation and child marriage.

SUBBING WHILST BLACK

One can imagine that there are general problems of SWB (subbing whilst black). Given the historical constructions of black women’s sexualities and the present-day violence that continues to be marshalled against black women both across the continent and in the diaspora, it is not a stretch to imagine that in entering an interracial BDSM situation black queer women might be inundated with images straight out of a documentary on colonisation or slavery. Even in sexual interactions that do not involved interracial contact, the history and reality of social expectations regarding women’s submissiveness make this – at first appearance – a complex space to manage.

So why would a black queer woman and or a gender non-conforming person consider BDSM let alone find intimacy, joy and pleasure in acts that evoke ideas of violence and bondage, and that require submission.

Yet it is precisely the ability to navigate this nexus of pain, risk, pleasure and protection that many queer women on the scene seek.

POWER AND CONSENT: AN AGE-OLD BATTLE

In her Vice piece ‘The power of being a black woman in bed’, Michelle Ofiwe says ‘growing up, I realized that I encountered few narratives of tender Black women.’ She muses about how the perception that black women are ‘strong’ can make it difficult for them to vocalise and accept vulnerability. Within BDSM the notion of power – who has it, who to give it to and when to hold it – are central to the sex act.

Ofiwe points out there is a freedom in exploring new ways of sex and pleasure, a queering of interactions that subverts and explores notions that are taken for granted within more mainstream ‘vanilla’ notions of sex.

Muthoni, a queer activist from Kenya, unpacks the role of BDSM in helping heal scars caused by sexual violence. She says, ‘It heals the history around the woman’s place in sex as a recipient, therefore the sole purpose of a man’s pleasure. BDSM gives the woman the agency to clearly define and negotiate their power.’

For Muthoni, ‘It’s liberating to up notions of power in a trusting space.’ She explains that the ability to negotiate the sex that you want is empowering and liberating. Being a queer woman from East Africa, safety is a constant negotiation. There is a need to compromise your bodily autonomy all the time. BDSM forces you to say ‘yes’. It makes you agree on the rules. It rewards you for asking for more when you want it and for saying stop when you don’t. Even as power is central to BDSM, so too are trust and consent. That’s where the pleasure lies.

As Muthoni concludes, ‘BDSM demands that sex and power is mutual and shared willingly and honestly.’

Kgothatso, a queer woman based in southern Africa, says ‘rope reminds me of the liberation I find in BDSM. It reminds me that there is much freedom in being able to relinquish all control.’

It is both in being able to be in control and at the same time relinquishing control that these women can explore their ability to negotiate power. Although there are assumptions that the kink scene is about imposed pain and violence, the reality is force is not the rule in BDSM interactions. Instead, when it does occur, it is ‘an unwanted exception’.

Consent is defined as ‘informed agreement between persons to act in an activity which is mutually beneficial for everybody involved’. Whereas in heteronormative sexual interactions, consent is often riddled with grey areas, in kink, it is essential that these issues are

addressed head on. Because pleasure and pain are bound together, kinksters are generally meticulous in addressing the boundaries. Tshegofatso, a sex positive blogger, feels strongly about this. ‘Kink is all about consent. Within the kink world I have felt I have the power to consent more than I have in every other aspect,’ she says. For her consent is one of the most important and central parts of the kink experience. Tshegofatso considers sexual growth and knowledge fundamental parts of BDSM. She says she was lucky to be exposed to kinksters who conceptualised consent in a way that made her feel safe and able to explore her desires.

She explains: ‘When comparing that [engagement with consent] to non kinksters I have been able to find a lot more control and a lot more able to experiment with things that previously had been uncomfortable with as I know in the kink world I am constantly learning.’

When one considers that at the core of BDSM are the notions of consent, openness, transparency and trust, one can see why this realm would allow so many women to reclaim sexual desire and autonomy.

It is also evident why the practice is queer – it is too liberating, too grounded in choice and equality to form a part of patriarchally defined sex practices.

S E X U A L E X P L O R AT I O N : P I N P O I N T I N G

PLEASURE

One of the most confronting and liberating aspects of BDSM is the fact that typical gender roles and ideas of sexuality do not apply to BDSM. One of the women I interviewed – Thabile, a South African lesbian – stated, ‘Kink simply allows me to be without judgement.’ She emphasised that kink allows her to explore what feels good to her and take it as far as she wants to, and then allows her to stop if that’s what she wants to do too.

Thabile explains that for her kink ‘is a safe space of exploration and just being. A space where expectations are clear and worked towards, not just by yourself but with other people that care to learn you and work on keeping you safe.’ She explains that, ‘There are a lot of dynamics in life that one cannot control.’ For Thabile, ‘the stripping of control also means the limiting of how one expresses themselves; so my involvement in kink is me trying to learn about myself in an environment that enables authenticity and the ability to just be damn right honest.’

BDSM gives women tools and a framework for clearly defining and negotiating their needs and their limits.

For these queer women the space is one in which they can delve into what makes them feel good, what gets them off, what sexually excites them and what they consider to be safe sexual engagements within a healthy, cognitive and communicative framework.

CONCLUSION

In private conversations and in their public art and media initiatives African queer women’s explorations of BDSM are subverting dominant narratives about who owns pleasure, who can dictate what happens to another person’s body and what good sex looks like. Through acts of submission and domination they are reclaiming their bodily autonomy and their right to sex that is safe, empowered and pleasurable. Queer women are choosing what feels good and what is good. In a time and space where many women are not able to take sexual pleasure for granted, this is a rare privilege.

The private (and public) conversations about sex lead us to understand that different notions are central to the experience of pleasure, sexuality, sensuality and the erotic. As each of the women profiled above demonstrate, it is agency that makes sex so delicious. Queer women find a sensuous experience in kink – like when you are eating the exact meal that you want and sharing it with the dinner guests of your choosing.

Note: Thank you to the queer women who aided in the compilation of the ideas and quotes for this paper and those who gave their beautiful bodies for the images. You stay magic.

CITATION

21 A. Fulkerson, ‘Bound by consent: Concepts of consent within the leather and bondage, domination, sadomasochism (BDSM) communities’ (2010).

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions