SIBONGILE FISHER WAS hanging out with friends, eating burgers at Snack Boss, a restaurant in Tembisa, a township in the East Rand in Johannesburg, when she saw the link on Facebook: a post congratulating her. It was November of 2016 and she had won the Short Story Day Africa Prize. She had been absent from social media, Short Story Day Africa had been trying to reach her via email, and then she got a phone call: Rachel Zadok telling her she’d won. “I was in total disbelief for a good couple of days,” she wrote in an email to Brittle Paper. “I didn’t understand why? Why was I the winner?” But Fisher’s questioning of the recognition her work had received had nothing to do with the quality of her winning short story, “A Door Ajar,” a riotous imagination of a matriarchal community bound by as much love as violence. It had to do with her initial hesitation to enter for the prize. She had planned to only apply and be accepted for Short Story Day Africa’s Flow Workshop, but the organisation’s rule was that their workshop participants had to enter for their prize. And so, on the afternoon of the June day in whose evening she was to attend a concert by the American rapper J Cole, Fisher had gone to the Goethe Institut in Johannesburg, where the writer and editor Tiah Beautement was facilitating one of the Workshop sessions. And now that she saw the link, it felt like a dream.

Two years later, last week, in an office in Nigeria, Emmanuel Tochukwu Okafor was trembling. He had seen it on Twitter, his name, his face, and afterwards would check his email to see SSDA’s official message. He tried to steady himself, his phone had fallen to the ground, he heard himself, “Oh my God, oh my God,” gasping for breath, as his colleagues gathered, puzzled. It was his third time entering for the prize, and “All Our Lives,” the story that had now won it, had been written at a difficult moment in his life—kicked out of his house, living with his sister, with no job—and had taken form only over correspondences with his friend Karen Jennings. He was awash with grateful shock.

IT BEGAN AS a labour of love. In 2011, South African writer Rachel Zadok received a message from Daneet Steffens, then editor of Mslexia Magazine in the UK. Steffens “contacted me to ask if I would create a National Short Story Day in South Africa,” Zadok wrote to us via email. “She was launching one in the UK and wanted to see if she could get other writers to create something similar in their own cities around the world. The idea was to celebrate the short story on the shortest day of the year.” Although Zadok liked the idea, she found that the shortest day in the northern hemisphere is the longest in the southern hemisphere. She decided to launch a different organisation instead, registered as a non-profit in the Republic of South Africa, and called it Short Story Day South. Short Story Day South would celebrate the short story, and hopefully, in the advent of resources, organize a prize and anthologies.

Zadok began trying to get as many writer events happening across South Africa as she could: Cape Town, Johannesburg, Pretoria. But she also wanted to reach the small, secluded towns. In Mossel Bay, one of such secluded areas, she had a family friend who was willing to set up a local event if Zadok could find a writer to do a reading. Zadok reached out to the publisher Colleen Higgs, who suggested she ask Tiah Beautement. “Colleen Higgs says you are in Mossel Bay,” she wrote to Beautement. But given the distance, Beautement found her offer odd. “We are a good four to five hours drive from Cape Town, nearly a twelve hour drive from Johannesburg,” Beautement explained to us via email. “They have plenty of talent in their cities without needing me.” Still, Beautement said yes.

After her public reading for the project, Beautement involved the local library and one of the government schools, and a series of events were held in both venues. “The children and I discussed storytelling, their various forms, and we wrote chain stories,” she said. “The adult writers in the cities were writing long chain stories: one writer writes for X amount of time, then the story is passed on to the next writer. That was too much for the children. Instead, we did it line by line. I, or a teacher, would do a line, then a child would suggest the next one, and on we went, until we had a piece of flash fiction.” In support, Zadok posted the writings of the young writers on the organisation’s old Website, alongside the chain stories by professional writers. The following year, 2012, Zadok officially asked Beautement to join the organisation.

At first Beautement said she couldn’t. Her role was to be the Kids Coordinator: oversee a children’s contest, and, eventually, put together anthologies of their work. “I was honoured, but declined. I was at the initial stages of being diagnosed with fibromyalgia and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome,” Beautement explained to us. Fibromyalgia and Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome are illnesses that create great pain and exhaustion. Because it had taken Beautement long to get the proper diagnosis, and given a lack of proper treatment, her condition was deteriorating. “I was dropping things, couldn’t hold a normal size coffee mug, couldn’t cut up food, and worst of all I was losing the ability to type. There were times I couldn’t work at all.” To manage this, she was taking a lot of breaks, throughout the day. So she suggested that Zadok find someone else. But Zadok encouraged her to accept the role, suggesting ways to work around her health problems. “I was going to be working from my own home. If I needed to take a day off, fine. I just needed to get the job done.” The success Beautement recorded with her new routine had a transformative effect on her own self-confidence: she could still have a work life while living with the new physical challenges.

While the new organisation ran for two years, covering Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Botswana, they began receiving messages from writers across the continent, asking if they too could participate in the project. “Within those two years I realised that what we needed as writers in Africa was something very different to writers in the U.K.,” Zadok said. “We need somewhere to showcase our work, get our voices out without the intervention of the West’s idea of Africa, and basically write and publish what we want to write.” This realization led to changes in the project. It was renamed Short Story Day Africa, with South dropped to reflect the continental nature it was assuming. But even the new name quickly became something of a misnomer. This was no longer merely a project celebrating the short story on the shortest day of the year: it had become an institution dedicated to developing writers and editors, to showcasing their work, had become about reclaiming the idea of what it meant to be an African writer, about subverting preconceived notions of African Stories.

BY 2013, SSDA’s efforts had drawn more attention and among its admirers was Elizabeth Wood of Worldreader, who offered the project $2,000 in exchange for stories. It was with this money that Short Story Day Africa announced a themed competition from which the best entries would be collected in an anthology. Then Nick Mulgrew became involved. It was this expanded dynamic between Zadok, with her recognition of what the project’s writers needed including the workshops and editing mentorships, and Beautement, with her ability to be practical and implement ideas, and Mulgrew, with his book-making and branding skills and fearlessness in marketing, that elevated the project into what it eventually became, what only a potent mix of balanced reasoning and crazy optimism could have made it.

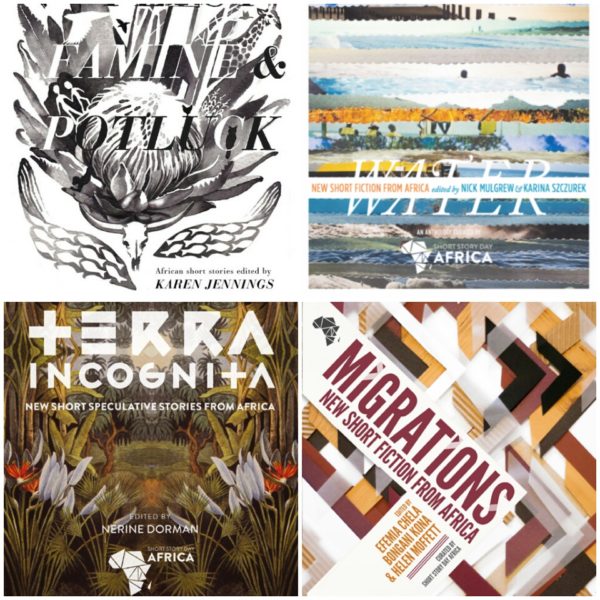

Short Story Day Africa’s inaugural competition theme, “Feast, Famine & Potluck,” centered around food: the abundance of it, the lack of it, the communities created through and for it. The team of readers included Zadok, Beautement, Caine Prize 2007 winner Henrietta Rose-Innes, Diane Awerbuck, Karina Magdalena Szczurek-Brink, Alé Steyn, Na’eemah Masoet, Sheryl Kavin, Lindsay van Rensburg, and Casey B Dolan. Petina Gappah, Isabella Morris, Consuelo Roland, and Novuyo Rosa-Tshuma were the judges. Kenyan Okwiri Oduor’s “My Father’s Head” was revealed as the winner and recipient of $1,000, while South African Jayne Bauling’s “Choke” and Ghanaian-Zambian Efemia Chela’s “Chicken” were adjudged first and second runners-up respectively. All three appeared in the print anthology Feast, Famine & Potluck: African Short Stories, edited by Karen Jennings and Zadok and published in 2014. Feast, Famine & Potluck received more attention when Oduor’s “My Father’s Head” and Chela’s “Chicken” were shortlisted for the 2014 Caine Prize, with Oduor going on to win.

For 2014, Short Story Day Africa changed the competition theme to “Terra Incognita.” Samuel Kolawole, Jared Shurin, and Richard de Nooy were invited to be judges. South African Diane Awerbuck’s “Leatherman” was named winner, Namibian Sylvia Schlettwein’s “Ape Shit” and South African Kerstin Hall’s “In the Water” were first and second runners-up respectively. The prize anthology, Terra Incognita: New Short Speculative Stories from Africa, edited by Nerine Dorman and Zadok and published in 2015, collected only speculative fiction. With the SSDA Prize on her resume, Awerbuck, whose novel Gardening at Night won the 2004 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book (Africa and the Caribbean) and was shortlisted for the International Dublin IMPAC Award, explained that she now gets “invited to events that I probably wouldn’t otherwise—and I got to be part of the awesome continental ess/eff community.”

That year, following challenges trying to move it beyond Beautement’s Mossel Bay, SSDA scraped the Kids Project. It had produced two anthologies: Rapunzel Is Dead (2013) and Follow the Road (2014).

SHORT STORY DAY Africa’s anthologies follow roughly the same manner of compilation. The Board decides on a theme, then an announcement is made. Writers each enter a story between 3000-5000 words. The team selects volunteers who blind-read the submissions to come up with a longlist of 21—initially 19—stories, which are sent to the anthology’s editor. At the moment, SSDA uses an editing team comprising an Editing Mentor, currently Helen Moffett, and two Editing Fellows. After the stories are edited and look their best, the judges are invited to vote on the shortlist and the winner. The anthology is then published the following year. “Stories that do not follow the submission guidelines are automatically disqualified,” wrote Efemia Chela, who has since been SSDA’s social media manager and now helps in reading their slush pile, via email. “The stories are judged on innovation and uniqueness, relevance to the theme and creative use of language and plot.” In the three months after the longlist has been announced, the stories are developed with the writers through insistent tos and fros. “We really ask writers to push their work beyond their boundaries,” Zadok said. Awerbuck describes this rigour as “unique,” and thinks that “it’s hugely important that this aspect of SSDA continues.” Entry for the Prize used to be free, but it now requires $3. The fee covers part of the cost of the submissions platform they use, Submittable, as the organisation has little funding.

But does the themed nature of the prize not limit its reach? “You have to look at the project as a holistic structure,” Zadok explained. SSDA’s format as a development tool for writers warrants it: the Prize is the last but peak part of a whole which starts with the workshops, then the editing mentorship, then the development edits. It is important that the workshops and its participants across the continent use the same material so as to be on the same wavelength, and so a theme emerges as a tool for cohesiveness, allowing the workshops to both develop writers and to create awareness for the project. “You have to remember, other prizes look to already published stories where the work of selection and development has already been done. We don’t. We have to look at stories that are sometimes very raw, writers who have a spark but no craft experience, and we want those writers to be willing to look at the theme and expand their imaginations around and beyond it.” So far, the themes have centered on food, land, water, migrations, identity; for the 2018 prize, it is “Hotel Africa,” a call for “innovative short fiction set in the rooms, the passages, the bars and the lobbies of hotels across the continent, as well as metafiction exploring Africa as a hotel herself. If these walls could talk, what story would they tell?”

The 2015 Short Story Day Africa Prize, themed “Water,” received 450 entries, and was judged by 2006 Caine Prize winner Mary Watson, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, and Kwani? editor Billy Kahora. South African Cat Hellisen’s “The Worme Bridge” was announced as the winner of the R10,000. Alex Latimer’s “A Fierce Symmetry” and Mark Winkler’s “Ink” came in second and third places, and received R2,000 and R1,000, respectively. Edited by Nick Mulgrew and Karina Szczurek, Water: New Short Fiction from Africa, published in 2016, also featured fiction that explored murder, magic, family, and war.

“When I got the phone call that the winners had been announced I must admit I thought it was a bit odd that Tiah Beautement would be phoning to tell me that,” Cat Hellisen told Brittle Paper. She had never thought of entering for short story competitions given that her work is “very much genre.” But when SSDA announced the “Terra Incognita” theme in 2014, she entered, and found her work on the longlist and in the anthology, and decided to enter for the “Water” theme. So when Beautement phoned to tell her that she won, the first award of her career, it took her some minutes of confusion to understand that that was what Beautement was saying. “I was incredibly happy. As the stories were anonymously judged, it was even better knowing the story won on its own merit.” “The Worme Bridge” has now been translated and used in librarian conferences. “That would not have happened if I had not won, and it was a morale booster when I desperately needed one. And as a venue that is open to and welcoming of speculative fiction, that is very important to me and the other writers of African birth and heritage who often don’t have a local venue willing to accept speculative and genre fiction as valid and important within the literary conversation that Africa and the African disapora are having.”

THE YEAR 2015 was significant for Short Story Day Africa. It saw the continentalisation of the project, the initial lack of which caused criticism that Zadok thinks is “a fair one.” Short Story Day Africa had grown organically on social media and blogs, and crucially, through word of mouth. Having started in Cape Town, most of the inaugural participants lived in the city. With each year, more participants from other parts of South Africa joined, but the demographic was roughly the same—South African. For their 2015 Prize, a huge amount of work was needed to mitigate against its continuance: SSDA’s approach to publicity was restrategised; more people were reached; more writers from more countries were responsive. The 2015 Prize anthology, Water: New Short Fiction from Africa, saw the project “take off beyond the borders of South Africa.” The progress of 2015 set the tone, chronologically and otherwise, for 2016: the year in which the Short Story Day Africa Prize, by virtue of its stories, became the best-regarded short fiction prize on the continent.

But before this happened, something else did: Tiah Beautement, so central to the organisation’s becoming, left in August of 2016. The need to focus on her own writing came calling, as did her health. (She has since joined The Single Story Foundation journal, where she is Managing Editor). However, her leaving came at a time when the project had grown to include a bigger team of enthusiastic writers and editors: Nick Mulgrew, Karina Szczurek, Helen Moffett, Rahla Xenoplous, Jason Mykl Snyman, Efemia Chela, Mary Watson, Isla Haddow-Flood, and Cathy Shepherd.

“MIGRATIONS,” the theme of their 2016 prize and anthology, required “a crop of short fiction that will bring a fresh, urgent perspective to one of our most profound phenomena, and the basis of all our greatest stories”—movement, “settling, unsettling, fleeing, seeking, resting, nesting and sharing stories, experiences and myths.” The theme received 450 entries, from 29 countries, including, for the first time, from North Africa. Sindiwe Magona, Hawa Jande Golakai, and Tendai Huchu were invited to judge the entries. South African Sibongile Fisher’s “A Door Ajar” was the winner, with Nigerian TJ Benson’s “Tea” and South African Megan Ross’ “Farang” named first and second runners-up respectively.

The anthology Migrations: New Short Fiction from Africa, co-edited by Efemia Chela and Bongani Kona under Helen Moffett’s mentorship, featured stories that range from the quirky to the assured, from the standard to the stylistic, a good number of them in lush prose. Fisher’s winner “A Door Ajar” centers on a family, and community, of females for whom life is a tough mix of violence, love, betrayal, tradition, and an insatiable thirst for home. Through sentence after sentence of resonating portrayal, its matriarchal culture is fleshed out, in both its violent normality and its beautiful placement of femaleness. TJ Benson’s “Tea” is a tale of apprentice porn actors—a Tiv female and a German male—who murder their employers in Italy and, with only a rudimentary understanding of English, must find a way to communicate in order to avoid arrest. It is told with cinematic range, in plainer prose that does not hide its movie influences, and, in its multicultural shot of human-trafficking, becomes a critique of the human need for, and adaptation to, communication. Megan Ross’ “Farang,” set in Thailand and South Africa, peaks in style and texture. Here is an aching romance, through intimacy and companionship and pregnancy, a reflection on love and language, foreknowledge and inevitability, in prose so lyrical and controlled it moves like a spring. Kenyan Christine Odeph’s “My Sister’s Husband,” republished on Brittle Paper as “Our Husband Grief,” is an immersion in a breaking family’s tragedy, with a narrator who is already dead.

If 2014’s Feast, Famine & Potluck suggested Short Story Day Africa as a space with the potential to influence short fiction from the continent, and 2015’s Terra Incognita helped in mainstreaming speculative fiction, and 2016’s Water reified SSDA’s relevance on the scene, it was 2017’s Migrations that etched SSDA short stories in the popular literary imagination on the scene, so that their announcements are considered as notable as any other African prize’s. And due to recognition from other literary spaces, Migrations is enjoying extended visibility. In August 2017, its top three short stories were shortlisted for the inaugural Brittle Paper Award for Fiction, alongside seven other works, including those by Binyavanga Wainaina, Petina Gappah, and Ngugi wa Thiong’o. In October, Ross’ “Farang” received the Award. This year, in May, another short story from Migrations, Stacy Hardy’s “Involution,” which had been on SSDA’s own shortlist, was shortlisted for the Caine Prize—the outstanding finalist in what, from the reactions on social media, is the much maligned prize’s astoundingly weakest shortlist yet.

DESPITE ITS GAINS and potential for more, Short Story Day Africa, like all major literary spaces, has faced criticism. It has been pointed out that the organisation is run by White South Africans, criticism that might have gained grounds as SSDA is based in a country whose literary culture is often accused of insularity, but one that is unfair when the circumstances are held up for scrutiny. SSDA began as, and remains, a volunteer organisation, and it was merely coincidence that most of the people who have answered their calls and are doing the administrative work for no pay are White and South African. But even in the early years of the Prize, the talk went beyond the organisation and into the race of their winners. “I was super-conscious the year I won of being White with a capital W,” says Awerbuck, whose win was met with a pushback from a high-end, White UK reviewer for whom, she told us, her story “Leatherman,” with its main character’s fear of the tokoloshe, seemed stolen from another culture. “There’s always the sense that someone of colour is a more necessary win—both for the resources in terms of prizes and opportunities to network, travel and be part of a public platform. But also because we all have a responsibility to make the right history here.” And consciously, the organisation is making up for these by inviting judges and slush pile readers from other African countries, and by handpicking local facilitators in countries where they have organized workshops.

How has the support from the literary community being? Nick Mulgrew (now founder of poetry publishing company uHlanga Press, which has published Koleka Putuma’s Collective Amnesia and Megan Ross’ Milk Fever) pointed out: “The staff at New Internationalist, our UK co-publisher, and certain writers and funders who put what little money they have toward supporting us. The support from these people has been wonderful.” But there are still issues, Mulgrew added: “Large funders are few and far between, as well as capricious. And then when you do manage to get a great book out, there’s sometimes strange criticism—not about the stories, which is always fair—but about how you got that great book out.” And he seems surprised at how far they have come: “Few people realize that SSDA started as a relative flight of fancy that suddenly realized it was capable of publishing stories worthy of winning the Caine Prize, and eventually holding writing and editing workshops not just in South Africa, but all over the continent.”

But this is an organisation so dedicated that it engages self-criticism seriously: the group itself identified problems with its blind-reading process. A helpful idea in principle, it did not, however, allow for the fairest playing field. “When you have published writers who have the privilege of working in a long-established publishing environment like South Africa or Nigeria, entering a story alongside a new writer from a country with no publishing industry, the published writers almost always get noticed,” Zadok explained. “Add that those stories are read blind by people all over the continent used to reading published work, great writing is going to be missed.” While blind-reading is still employed for their slush piles, editors and creative writing teachers—professionals used to reading raw, unedited work—are further invited to help out: a laborious process, as there are fewer volunteers, but one which, coupled with the judgement of the stories only when they are publication-ready, allows them to identify “so many wonderful gems.”

EVERY YEAR, a call is made for applications to SSDA’s Flow Workshops, twelve participants are selected, and then the workshops, facilitated by a local resource person, are held in Goethe-Institut centres around the continent, or in alternate venues in cities where there aren’t Goethe-Institut centres. In 2017, there were eight such programmes: the Nigeria workshop was facilitated by Saraba co-founder Dami Ajayi in Lagos; the Cameroon workshop, by Bakwa editor Dzekashu MacViban in Yaoundé; the Namibia workshop, by Sharon Kasanda in Windhoek; the Kenya workshop, by Anne Moraa in Nairobi; the Ethiopia workshop, by Agazit Abate and Zadok in Addis Ababa; the Rwanda workshop, by Huza Press founder Louise Umutoni and Zadok in Kigali; and the South Africa workshops, by Efemia Chela in Johannesburg and by Zadok in Cape Town.

And there is a huge demand for their workshops. In 2016, they held an open workshop at the Be re e ne re Literary Arts Festival in Lesotho, and expected twenty attendants, but over forty people turned up. SSDA designs the workshop material, the same structure and free writing exercises for all participants irrespective of location, in a way that allows participants to work on their Prize entries in line with the theme. The 2018 workshops will be held at the end of July, in Zambia, Malawi, and Zimbabwe, with funding from Beit Trust. Meanwhile, team member Jason Mykl Snyman is presently developing a new project called Inkubator, an online workshop for writers, which will replace SSDA’s initial online workshop, #WriterPrompt, and serve as a forum for writers to get feedback and help on their SSDA entries.

THE 2017 SHORT Story Day Africa Prize, themed “ID,” referring to both identity and the psychoanalytic concept of the Id, made Emmanuel Tochukwu Okafor the first male and the first Nigerian to win. His “All Our Lives,” a multiple-identity story examining the lives of disaffected men who drift into Nigerian cities in pursuit of a “better life,” was described by the judges as “wry, cleared-eyed, humorous and compassionate.” Two stories came in joint second place: Ethiopian Agazit Abate’s “The Piano Player,” “a brilliant inversion of the ‘African abroad’ narrative as it presents snapshots of life in Addis Abada through the eyes and ears of a pianist in a luxury hotel bar,” and South African Michael Yee’s “God Skin,” which weaves “together alienation, forbidden love and intimate violence against a subtle backdrop of the scars of Liberia’s civil war.” Okafor will receive $800 and Abate and Yee, $150 each. This was Okafor’s third try; his second try, his story “Leaving” had appeared in Migrations; his first try, he’d responded to SSDA’s 200-word #WritingPrompt and, overwhelmed by feedback that made it feel “like a physical creative writing workshop,” entered and wasn’t longlisted. “The editing experience was painful, soul-destroying,” he said of the last two years, “yet my biggest reward from entering the prize.”

The top three stories for the 2017 Prize will appear in The Johannesburg Review of Books. The mother anthology, ID: New Short Fiction from Africa, edited by Helen Moffett, Nebila Abdulmelik, and Otieno Owino, and supported by the Miles Morland Foundation, Goethe-Institut, and Worldreader, is co-published with New Internationalist in the U.K. and will be available both in print and as an e-book. But “distribution of African books to Africa is such a tricky business,” Zadok said. “What we really need is co-publishers on the continent willing to publish. And for someone to sort out distribution.”

The SSDA Board Members—at the moment, they are Rachel Zadok, Helen Moffett, Jason Mykl Snyman, Karina Szczurek, Isla Haddow-Flood, Rahla Xenopolus, and Mary Watson—mostly work for no pay. When there is funding, it is dispersed on a project-by-project basis, and Board Members who work on those projects are remunerated for their specific work, as are those to whom SSDA outsources project elements. But the team is optimistic—about challenging notions of and building African writers, about presenting African storytelling, expanding its range of possibilities—the team is defiantly optimistic. Zadok’s mantra is the line from Field of Dreams, the 1989 Kevin Costner baseball film: If you build it, they will come. And early this year, the organisation welcomed a new Board Member in a development that stunned observers: Lizzy Attree, Director of the Caine Prize since 2011. With its pedigree significantly burnished, Short Story Day Africa has emerged, even without major resources with which it could have branded itself, as the most important institution for African short fiction.

Literary prizes judge and elevate writing, but how do you judge literary prizes? By gauging their power, their media coverage and network? Their acclaim, how much remarkable writing they have launched? Their transformative impact, how they shape or even dictate literary cultures or genres? Their marketability, how much writing they sell? Their influence, how many careers they have launched? Or their prize money, how much dollars and pounds go to their winners? How about their investment, in an industry that on the continent can factually be described as developing, in nurturing both writers and editors? How about their initiatives being held in the continent, in eight of its countries simultaneously? How about their finding ways to tackle the problem of storytelling clout, how much of it the people for whom the prize is meant actually have, how many of their stories they get to tell and in what ways—engaging the future with solutions? Which of these count the most, and to what extent, in granting that most distinguishing of adjectives, “leading,” to a literary prize?

“It’s early days yet as the prize is just going into its fifth year,” Hellisen told us, a response to a different question that might as well have been for this one. “But I hope to see SSDA rivaling things like the Caine Prize in terms of importance and prize money.” As right as Hellisen is with the factors she mentions—history, publicity, money—over the past two years, the SSDA has had no rivals where it matters the most: quality, nurturing.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this profile stated that Tiah Beautement left Short Story Day Africa in 2015. It was in August, 2016 that she did so.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions