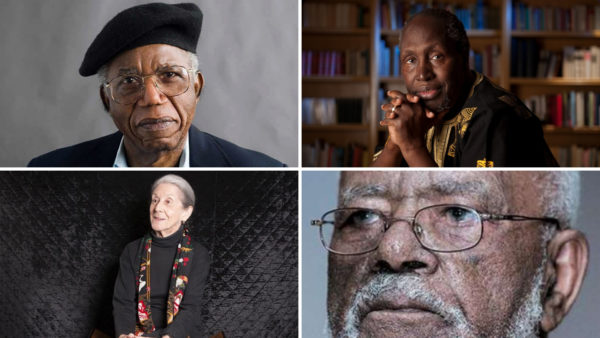

Once in a while, an essay comes along, stinging and unrelenting, that tears readers into camps of agreement and disagreement. Three days ago, UW-Madison professor Ainehi Edoro, founder of Brittle Paper, came up with such an essay. Published in Africa Is a Country, “Gods of Fiction: African Writers and the Fantasy of Power” uses Chinua Achebe’s positioning of the novelist as teacher to critique the assumptions and practices that defined the relationship between the African writer and the African reader in the first generation of modern African literature, and of the language used by the writer to create a hierarchy in that relationship.

“Gods of Fiction” goes further to point out how the use and normalisation of such language and unequal relationship have led to contemporary novels that make you “want to get out your check book and send a donation to a humanitarian organization,” turning “the act of reading into the study of social ills and moral virtue.”

“As students, African readers are placed in a developmental trajectory, always working their way up to becoming better people and better readers,” Ainehi writes. “The problem with this setup is that the novelist has no incentive to change his or her vision of the reader. A teacher is not a teacher without students, so if the African writer wants to stay in business, he or she has to keep readers in their status as students. Four decades after Achebe instituted his pedagogical regime of literature, Nadine Gordimer is still complaining that the African readership is at a ‘primer-book and comic-book level.’”

Expectedly, the essay has set off reactions on social media.

Here is a Twitter thread by Zimbabwean novelist Novuyo Rosa Tshuma, who uses her the reception of her novel House of Stone to address some of her concerns with the essay:

Interesting essay by @brittlepaper —too harsh on Achebe Generation!You can’t read that art wout appreciating the period they were writing in.Storytelling as art+education is an Afro-rural tradition,tied to local lang—my grandparents did it,& it does not take joy out of the story https://t.co/sxho5Uft0n

— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

2.Tbh the very notion of “African writing” is problematic esp as “Africa” is an idea—started at the 1884 Berlin Conf that “created” Africa—not yet rooted in socio-economic-political reality. ie there is no cohesive Africa right now,we are still very bound by North-South relations

— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

3. We can’t talk about tastemaking re art,wout appreciating global influence of our current Empire USA on taste.“African writing” is embroiled in tastemaking that comes from of Empire outward, & not starting inward,bc there is no cohesive “Africa” besides various competing ideas

— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

4.With a murky,still-unrealised “Africa”—who is one “talking to”?What society is one writing out of?Art is not abstract—comes out of real & specific locales. Germans writing in German know who they are writing to.Even in the USA,there’s nothing like uniform “American” literature!

— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

5. “African writing” is export literature—fulfilling very purpose Africa was created for 1884 Berlin https://t.co/5S5Uw2jGhy’s the one lit where international readers believe African writers are continuing colonial tradition of “explaining or entertaining them w Africa.”

— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

6. Rooting lit in localities 1st,& understanding links between them—say across nations in our vast continent—changes how we understand lit’s engagement w world. Eg Trump as President has seen rise in engagement w matters surrounding USA culture in USA lit.This makes sense?

— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

7. To understand misreadings that arise from “African writing”—#HouseofStone tackles big Zimbabwean https://t.co/Ho5grfsWX1’s a novel arising out of its specific locale,which is why it unwittingly speaks to urgent matters in Zim,& why Zimbabweans are interested in engaging w it.

— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

8. Readers from Nigeria & Kenya have also found connections—did not/could not have had them in mind,they are so vast & so that’s impossible.USA,European lit etc never thinks of us as readers—always this lit begins from its specific societies—but some of that lit touches us too!

— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

9. As an “African novel” #HouseofStone becomes a “big topic”

novel.Which is why I prefer it as a Zimbabwean novel—it matters for Zim as a space,I never have to question that,& while writing it made sense to me why I was writing this,it makes sense to Zimbos why it’s being written— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

10.Thinking of “Africa” while writing,I must now rack my brains—whose Africa,& whose concerns must I value? Once again,as an idea,this “Africa” asks the “African subject” to put aside their own societies to serve “higher purpose” of “Africa”—export lit in our neocolonial times

— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

11.Another thing we must appreciate is that Achebe Generation lit comes under attack today precisely bc we are in a continuation of imperialism w USA as Empire. The future Ngugi et al had ambitions for—did not come to pass. This is part of the present tensions re “African lit”

— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

Ainehi replies:

Afro-rural? Read The Ozidi Saga. Read Ifa Divination literature. Pre-novelistic African writing are actually way more fluid and experimental and not overtly didactic as the Achebean instructional regime of literature.

— BRITTLE PAPER (@brittlepaper) November 25, 2018

Understand that this was the ‘60s. African literature was all over the place. The “novelist as teacher” approach was Achebe and co’s attempt to consolidate African Lit as a genre, market, aesthetic practice and field of study.

— BRITTLE PAPER (@brittlepaper) November 25, 2018

Dami Lare, a reader, chips in:

Ozidi Saga? Ifa Divination poetry? Pre-novelistic African literatures are as overtly instructive, if not more. Any and all of the odus (ifa) you so mentioned are crafted around, as principle, the inherent impulse of the practitioners to teach.

— Dami Lare (@Oludamiii) November 25, 2018

Practitioners as ambassadors of a knowledge system that is. Achebe and his generation merely, to put it simply, worked a recognizable (political) framework for what has always been obtainable from/in African literature.

— Dami Lare (@Oludamiii) November 25, 2018

There were agreements with Tshuma’s reading:

I agree with you, too harsh indeed. The writer also discounts the fact that Achebe and Ngugi were ACTUALLY teachers, this reflects in how they write. Interesting read though

— Memezi Nyoni (@memezi) November 25, 2018

To then say “moralistic didactic bent of…has its roots more in Christianity than…” is suspect as it sidelines the pedagogic spirit framing African literary system–if by pre-Modern writing you mean literature. Ozidi as folklore epic suggests otherwise

— Dami Lare (@Oludamiii) November 25, 2018

Kenyan writer Mehul Gohil tries to limit the problems to realist literature, contending that speculative fiction exists beyond the major concerns:

I don’t think all fiction writers in Africa work in the landscape they created. Their landscape is not the only landscape nor is it the most beautiful and most diverse one. There are other landscape. Even outerspacesccapes that have nothing to do with nor need Ngugi or Gordimer.

— Mehul Gorilla (@mehulgorilla) November 25, 2018

Nigerian writer Molara Wood broadens the geographical scope of the conversation:

This thing about the implied reader is in nearly every great theoretical work by writers, from Kundera to Naipaul, Baldwin to Richard Wright, Rushdie to Arundhati Roy, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker. Did Graham Green see himself as the reader’s equal? Kingsley Amis? Virginia Woolf?

— Molara Wood (@molarawood) November 25, 2018

Nigerian writer Kola Tubosun finds a humourous angle to the conversation;

When a controversial essay by @brittlepaper gets pummeled online, on which platform do we go to discuss it?

— Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún (@kolatubosun) November 25, 2018

The conversation touches on that review of We need New Names that inevitably enters most conversations on the idea of “African Writing”:

Thanks.NoViolet Bulawayo’s We Need New Names=a gorgeous classic—Habila’s review that set off the storm is a reflection of the crisis & misreadings inherent in ‘African writing’. Mukoma wa Ngugi wrote an excellent essay distilling this controversy of ideas: https://t.co/wQOv8do5cC https://t.co/cZEYK6atMK

— Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (@NovuyoRTshuma) November 25, 2018

Over on Facebook:

Benson David, an editor of 20.35 Africa poetry anthology, writes:

Finally we can talk about this.

One of the very first rites of initiation into the study of literature at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, is getting ceremoniously introduced to Achebe’s flimsy and ultimately damaging dismissal of the mis-received idea, arts-for-arts-sake, as “deodorized bullshit,” that is, even before you have a chance to be properly introduced to the idea itself and what it really means, and that is, if you are lucky enough to be getting introduced to it by a person like Prof. Akwanya (who is treated as an intellectual outcast of sorts for trying to import western literary ideals into the den of African literature): every other person will most likely be toeing the line of Achebe–dismissing it, only this time more out of bigoted ignorance–or trying really hard to maintain a middle ground and be failing at it, because it is difficult in all honesty to find a middle ground in this case.

For four years, with like-mindedly troubled colleagues, I struggled rather rigorously with similar questions as Ainehi’s essay poses: between the novelist (or generally, the ‘artist’) as an instructor, historian, anthropologist, moral conscience etc, and the novel (or generally, the product of the ‘artist’) as an expression of culture, history and experience, where do you place the literary text itself as a work of art?

That is to say, if this is the artist, and this is what his product is, then where is the art?! If it is art, why is it not first and foremost defined by the principles of what it is named???? Why must art be art-for-education, art-for-instruction, art-for-the-preservation-of-history, art-for-enrichment-of-life, or art-for-anything-you-need-to-use-it-for before it can be valid as art? Why, for example, define art by its (I must say, coincidental) ability to preserve history, when we have historians and their history books? And if it is for moral instruction, then it can’t be art if it does not morally instruct?

You see, something does not add up. But your favorite African professors and postcolonial-type critics will never admit it. This was why, for four years, it was so easy for me to want to disagree with Achebe–the critic–while revering Achebe–the novelist. I think we are moving on from this though, howbeit slowly. For one thing, we have an essay like this one by Ainehi interrogating the assumptions that inform our passionate claim to a type of literature that is wholly African.

I am reminded now of a fight that happened about four or five years ago on this platform. It was amongst a relatively small circle from which came a set of people who I believe are taking (major) part in currently defining how we will think of African literature in the next fifty years, or less: on one side was the more traditional group who thought of the art of writing in strictly prescriptive, thematically restricted, “African” sense, and on the other side was the rather rebellious group screaming for art that is free of the burden of prescription. We are getting there.

See, if it is going to be called art, then it must first, foremost and uncompromisingly be defined by its ‘artness.’

(link to the essay in first comment)

This is a splendid essay. I love it’s composition. I just disagree with some of it’s views, that’s all.

The point of seeing arrogance in men who chose to truthfully portray their country the way it was (the way it still largely is), that is just unnecessary.

Yes, I understand the need for equality, beauty, sugarcoatings and everything else contentment and patriotism apparently entail. But in Achebe and Ngugi’s writings, we should not see proud ‘god aspirants’ because they loved hard enough to want to fix the broken. Africa was sick, our cultures were dying. And when we wrote we did not write ‘our own’.

Achebe saw the country for what it was. I am happy he made attempts to ‘fix’.

But, good essay still. Good essay.

READ: Gods of Fiction: African Writers and the Fantasy of Power

Tell us what you think.

Lynne December 16, 2018 16:08

Thanks a bunch for sharing this with all of us you really understand what you are talking approximately! Bookmarked. Kindly also talk over with my website =). We could have a hyperlink trade contract between us