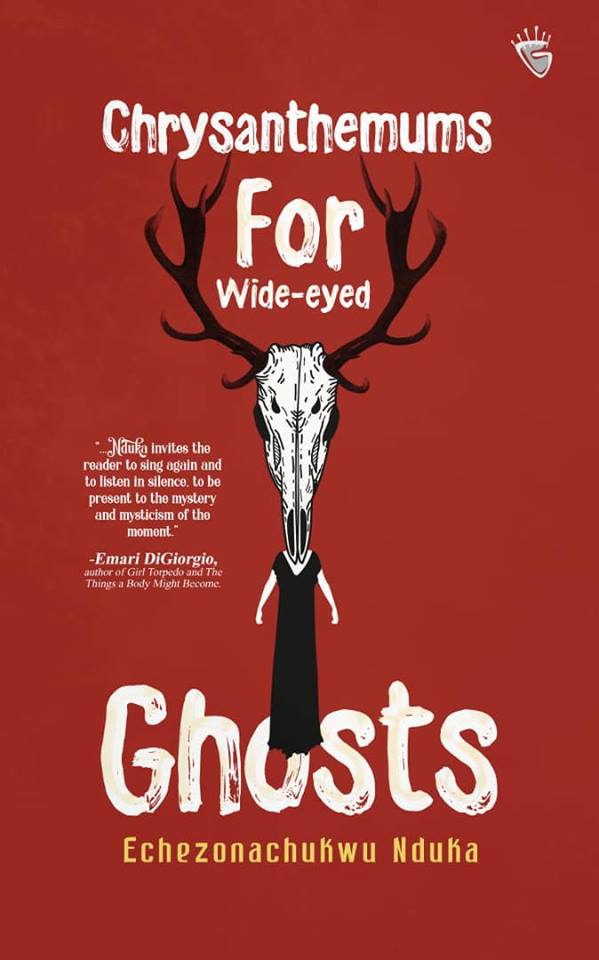

Echezonachukwu Nduka is a Nigerian poet, classical pianist, and musicologist. His poems have appeared in several publications including Saraba, Jalada Africa, Bakwa, River River, Bombay Review, Brittle Paper, Sentinel Literary Quarterly, African Writer, Sentinel Nigeria, A Thousand Voices Rising: An Anthology of Contemporary African Poetry, among others. In 2016, he was awarded the Korea-Nigeria Poetry Feast Prize on World Poetry Day. Echezonachukwu Nduka holds degrees in Music from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and Kingston University London, UK. Chrysanthemums for Wide-eyed Ghosts is his debut collection of poems.

Umezurike

Chrysanthemums for Wide-eyed Ghosts is your debut collection, with over 70 poems. How long did it take you to put it together? What limitations did you face? What did you learn in the process?

Nduka

My first draft was ready in 2013, so I would say the process took about five years. The first thing I learnt was patience. As a young poet, and as a prospective first time author, there was that urge to hit the press so as to join the league of published poets. I sent out poems to literary journals and got my fair share of rejections. But of course, the few publications I got spurred me. When I received the first editorial feedback on my first draft, it was so brutal and honest that I nearly questioned my artistry. I was limited in style, structure, and scope. I needed to read more than I wrote. I had to rewrite some poems and jettison those I thought were beyond redemption. In addition, I learnt that every poem needs time to breathe and become. By the time I sent out my final draft in the second quarter of 2018, it had become an entirely different work from my first draft. The title had changed twice as a result of several revisions. It is possible for poets to outgrow their early poems. I like to think that every poet has that poem they never want to be associated with. And that, I would argue, marks the metamorphosis of the young poet.

Umezurike

I like the title, fantastic, especially the imagery of “wide-eyed ghosts.” Chrysanthemums symbolize a lot of things in different cultures – joy, longevity, even death, so could you tell us why this imagery captivated you? What inspired the title?

Nduka

Thank you, Uche. It was inspired by the flower’s multiplicity of meanings. I am fascinated by the intersections of love and death, the paradoxical mix of sorrow and joy that we often experience as humans. There are no absolutes, if you think of it. I took the title from one of the poems in the collection. You would find that in the poem itself, chrysanthemums are being shared as an act of joy and love right in the midst of mournfulness. Haven’t we seen, in some cultures, where the bereaved and guests dance to lively music in a funeral? There are justifications for that, which include honouring the dead, but that does not take away its paradox. Imagine that some people meet the love of their lives in situations so dark, romance should be the last thing on anybody’s mind. Yet, it happens. On the other hand, that plurality lends itself to the ontology of poetry which rejects singularity of interpretation. The imagery of “wide-eyed ghosts” is my imagination of a possible reaction by the dead to the activities of the living. Sometimes, I find myself wondering how the ghost of an acquaintance would respond to certain events.

Umezurike

Funereal images such as death, ghosts, and bones overlay “Living near St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery.” How do you go about creating a poem? What’s the process like for you? The erotic and the elegiac, the joyful and the sombre, saturate your collection – was this a conscious decision to organize it in this way?

Nduka

Yes, it was quite deliberate. I felt the need to have such thematic diversity in an order that affirms the various layers of humanity, while also engaging the otherworldly. Death is part of living, and the dead have their goings-on acknowledged in numerous cultures and religions. But again, I think my fascination with the dead, ghosts, and such images might have something to do with my childhood. As a cadet in the Boys’ Brigade, it was our routine at the time to play at funerals, and that included going to the morgue, and also seeing the bodies while we played at viewing sessions. In that particular poem, as I have mentioned earlier, I was playing with the idea of ghosts interacting with themselves and also reacting to the world of humans. That poem took quite a while because I felt the need to let it flow on its own terms. I do not have a definite process of writing. I think it all depends on the poem. While some poems require an aching urgency, others ask you to take your time on reflections before the actual writing.

Umezurike

In “where music lives,” the poet urges us to take a walk on the street where “Music wields a painter’s brush; spilling colours on verses/and pages.” I’m struck by the poem’s kinetic rhythm. Do you write a poem according to a definite prosodic form? What decides the rhythm for a poem? Can you describe your own experience of writing towards certain particular forms? For instance, a poem such as “Flames”?

We stood on the flames to peep into heaven, to ask a blue-

eyed angel at the gates of light if angels sing RnB or rap, if

Jesus owned a baroque trumpet or classical guitar,

if egg-stew is served on arrival.

Nduka

I have since realized that each time I insisted on a particular form, the poem sometimes sound forced. And this is what every true poet should guard against. The poet’s first duty is to listen. Poems require our attention in the writing process so that we don’t get in their way. Some poems take over from the poet midway, and ultimately decide their form and direction. This is true for me. Poetry is sonic, and rhythms become clearer when we read out loud. So, I read my poems to myself and pay attention to cadences and enjambment as much as I can. Before I wrote “Where Music Lives,” I already had the idea fully formed, because I was actually responding to a debate on the ontology of music. But when I started writing, I found out that the idea would be best formed in couplets. The poem flowed and I ended up with twenty couplets. Rhythmic structures are crucial to a poem’s musicality. And since the poem’s primary theme was music, I thought it was appropriate to work out a definite rhythmic structure in couplets. However, for a poem such as “Flames” which is free-verse, I tend to take liberty with regard to rhythm. On the whole, I like to think that my poems often decide their forms. My job is to pay attention and write as I conceive them.

Umezurike

While reading the segment “Bambari,” I recall the inter-community violence in a small town in the Central African Republic. Is there a story behind the Bambari poems, given the references to pleasures and “sweet frictions”?

Nduka

The Bambari poems were partly inspired by some acquaintances I had as an undergraduate. A room named Bambari was famous in certain circles for its occupant’s unending loud reggae music, romantic escapades, cigars, and booze. That said, there’s no particular story behind the poems. I chose to write and place them in that order so as to form a narrative. I simply asked myself, “If you were asked to read a short story and thereafter write eight poems retelling the same story, what would you write?” I thought about it for a while and responded with the poems which now make up that segment.

Umezurike

Ikeogu Oke said that, “Poetry, in perfect motion, becomes indistinguishable from music.” And your poetry references a lot of classical and pop music. What does music mean to your writing? How has your training as a pianist shaped your poetry? Would you have appreciated poetry differently if you didn’t have such a training?

Nduka

I hold the view that music and poetry are like two sides of a coin. If poetry is a living thing, then music and language are its oxygen. They both share similarities in sound, rhythm, form, and so on. Music is an integral part of my writing. For instance, the entire collection is in seven movements, each with a distinct theme connecting to the next. That is a basic feature in sonatas, concertos, symphonies and even pop albums, as it were. While most sonatas, symphonies and concertos in the classical era were composed in three movements (fast, slow, fast), I like to think of my collection as a symphony in seven movements. Has my training as a classical pianist shaped my poetry? That is not certain. However, I do know that there are parallels between playing the piano and writing poetry. Classical pianists are essentially trained to pay attention to techniques, styles, interpretations, forms, performance practices, and these are not divorced from the art of poetry. As a pianist, I know that certain pieces are only ready for public performance at their own time, no matter how long you practice them. And this is also true for some poems which evolve at their own pace until they are fully formed. If I didn’t train as a pianist, I probably would have still appreciated poetry the same way. You would agree with me that not all poets whose works reference classical music to a great degree are trained as pianists.

Umezurike

What inspired “grief in Two Movements”? Can you recollect what you were thinking of when you wrote this particular poem? Why are places significant for you – New Jersey? Newark?

Nduka

The first movement was inspired by a journey I made from New York to Newark. And the second, by a boy I saw near a church on the streets of Philadelphia. In both movements, I reflected on the axiom that there are people who genuinely wonder what others are going through, while comparing their lives and experiences. I think it is a common phenomenon. Sometimes you get on a train or a flight and you can’t help but notice a passenger whose countenance or disposition makes you wonder what’s going on in their lives. Such poems come from a place of observation, empathy, introspection, and finding layered meanings in the quotidian. To your question on the significance of places, they form an intrinsic part of our consciousness, memories, and imagination. Places contribute to the sum of our personality and existence. In fact, certain places tend to go with us even when we emigrate. I find myself writing about places not necessarily for the sake of identity, but because they have also become part of my creative process.

Umezurike

Reading “Inside the Old Room” was a sobering experience for me. It deals with memory, trauma, and death. Can you say just a few words about the stanza below?

There is no one left to say the angelus, none to measure

the size of silences, of loss resonating in midnight moans,

sighs, and hisses. That tiny bell atop the fridge rang at the

hours

of prayer…

Inside the old room, departures are doors opening to new

dreams.

Nduka

Death, loss, absences, and some transitional phases are existential realities we deal with from time to time. We accept the things we cannot change, and only relive them in memories and mementoes. What do we do with spaces left behind by our loved ones? When someone says something like: “Oh, I miss my mother. If she were alive today, she would have done so and so.” We come again to the realization that we are susceptible to the sting of absences. But on the other hand, some absences also lead to an entirely new phase of life which we come to cherish in the long run.

Umezurike

You cite Audre Lorde, Pablo Neruda, even Asa. Have they been an influence? Can you remember others who have influenced you as a poet?

Nduka

Yes, they have. In addition, there’s Derek Walcott, Gabriel Okara, Leopold Sedar Senghor, Chimalum Nwankwo, Ben Okri, Afam Akeh, Chris Abani, Ladan Osman, among others.

Umezurike

Finally, what is poetry to you? What do you think of your generation of Nigerian poets? And are you working on another collection at present?

Nduka

There seems to be a subtle alteration in my view of poetry each time I discover new works or re-discover old ones. To me, it is an art of sublimity that employs the finest of language in the interrogation of imagination and emotions. Poetry sees the unseen, re-sees the seen, and asks questions that we ignore, or wouldn’t dare to ask. And whatever responses we might have to some of these questions are never final. That said, I am of the opinion that my generation of Nigerian poets are brilliant, inspiring, and experimental. Amongst many, Umar Abubakar Sidi comes to mind for his avant-garde style and voice. I think a lot of poets now take time to improve on their craft and publish more in both local and international journals. To your last question, I am. But I must admit that it is a rather slow process for me because now as a classical pianist, I have to divide my time between music and writing.

***************

About the Interviewer:

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD student at the department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. His research interests include postcolonial literatures, print culture, gender and sexuality studies. An Alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), his work has appeared in several print anthologies such as On Broken Wings, Dream Chasers, Migrations, African Roar 2011, Daughters of Eve and Other Stories, Work in Progress & Other Stories, A Generation Defining Itself (Vol. 8),Weaverbird Collection, New Nigerian Writing, Water Testament, Calvacade, Author Africa, and Camouflage, etc.

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD student at the department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. His research interests include postcolonial literatures, print culture, gender and sexuality studies. An Alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), his work has appeared in several print anthologies such as On Broken Wings, Dream Chasers, Migrations, African Roar 2011, Daughters of Eve and Other Stories, Work in Progress & Other Stories, A Generation Defining Itself (Vol. 8),Weaverbird Collection, New Nigerian Writing, Water Testament, Calvacade, Author Africa, and Camouflage, etc.

Echezonachukwu Nduka: The Poet that wrote for Ghosts – The Question Marker July 15, 2019 12:29

[…] also seeing the bodies while we played at viewing sessions,” he told Uche Peter Umezurike in an interview. And it was his familiarity with corpses that helped him sustain composure as he played the […]