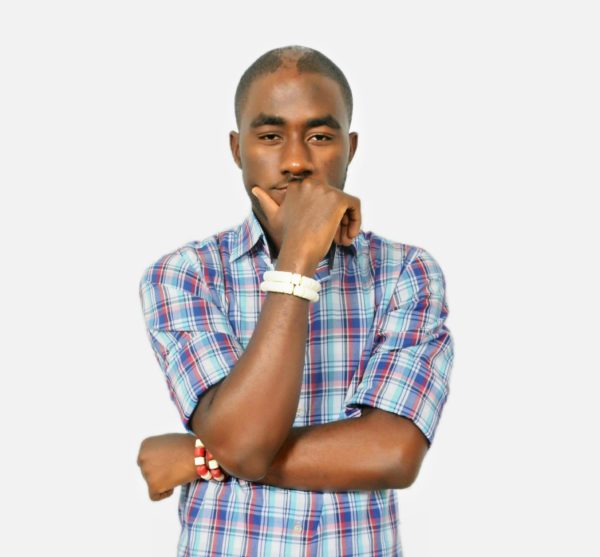

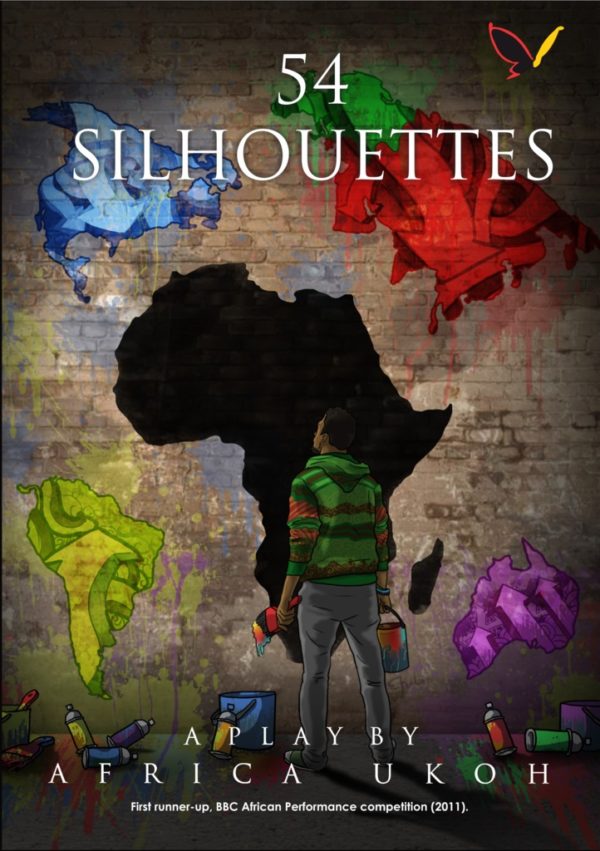

Africa Ukoh is a Nigerian playwright, screenwriter and actor. His play 54 Silhouettes was the winner of the Stratford East/30 Nigeria House Award and was also first runner up for the BBC African Performance Competition. It was produced as a radio play for BBC before its Jos stage premiere in 2013 and publication with Origami Books in 2018. Most recently, 54 Silhouettes has been performed in October 2018 as a one-man show by Charles Etubiebi in Lagos and at NEAP Fest in Brazil, and will be once again at the 2019 Lagos Theatre Festival on 12-14 April. In 2018, his play Token Dead White Guy was shortlisted for the BBC International Radio Playwriting Competition.

Ukoh co-wrote, with Abba Makama, the film Green White Green, which had its international premiere at the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival and is currently available on Netflix. He has written a number of other screenplays that raise questions about ethnicity, class, and society in contemporary Nigeria.

In 54 Silhouettes, an aspiring Nigerian actor, Victor Chimezie, has a big break when he gets a part in a Hollywood film set in Africa, but he quickly becomes troubled by how he is expected to portray a “generic” war-torn Africa by the bullying American producer Howard and his Nigerian agent Sonny. In Token Dead White Guy, Notu, a woman in the fictional African country of Molambia, tries her best to draw global media attention to a terrorist massacre of Molambians, while even her own compatriots are more interested in foreign football matches than human tragedy just down the road. Her answer is to seek out a “token dead white guy” to try to give the tragedy meaning in the world’s eyes. The film Green White Green follows a group of four teenagers who embark on a project to make a film about Nigeria and their search for an identity beyond the ethnic prejudices of their elders.

I sat down with him in July 2018 for a conversation about his recently published play 54 Silhouettes, which I reviewed for Daily Trust after its premiere in 2013, and its relationship to Token Dead White Guy and Green White Green. 54 Silhouettes can be found at bookshops in Abuja, Jos and Lagos, and Green White Green can be screened on Netflix.

Carmen McCain

It’s been five years since the Jos premiere of your play 54 Silhouettes in 2013, and you just published it with Origami Books. Could you tell me a little bit about what inspired the play?

Africa Ukoh

I got the idea way back in 2011, while watching an episode of Lost with my sister. There is this scene where they flash back to a Nigerian character’s past in what is supposed to be, I think, a Yoruba village, but the representation is all messed up. You have child soldiers. You have a mix of Yoruba and Igbo. It is just messy. I realized in that moment that I had a suppressed exhaustion with African stereotypes in media and I thought I could actually respond to this in a play. I had intended to enter for the BBC African Performance Competition, so when I saw that, I realized, oh, there is a story in here.

At first, I thought it would be about a novelist who hires a researcher, a Nigerian, and in the process of researching the book, the guy begins to see that this is going into this ugly stereotypical territory, but that just didn’t work. One day I was talking to my brother and something just clicked, “He’s an actor. He’s an actor, and he’s looking for a role.“ I literally just started writing it. The very first line of the play when I first wrote it was “So what’s it about?” It was almost as if I was talking to myself.

Carmen McCain

You said you wrote it with the BBC radio prize in mind, and it ended up being the first runner up. How did that process of writing and having it performed as a radio play affect how you revised and directed it as a stage play?

Africa Ukoh

Just hearing it performed, hearing professional actors—good actors—give life to the characters, the vocal texture, particularly the guys who played Sonny and Howard. Just hearing it come to life—it really makes certain things concrete for you—you get a better sense of rhythm and what worked and what didn’t work.

[In the stage play], I played Howard, my friend Charles Etubiebi played Kayode. So we both had the radio play to use as a vocal reference to turn to in terms of building character voices—with Howard you have to do an American accent and Irish accent, with Kayode you are doing a British accent and the generic African accent.

Carmen McCain

I’m glad you brought up the accents. If you look at the play, each person seems to be characterized by their accents, and then you also have these wonderful places where Victor and Sonny are so frustrated that they break into Igbo. Could you say a little bit about what you were doing with accent and language in the play?

Africa Ukoh

Because it was first a radio play, I was, with the accents, looking for a balance between auditory aesthetics and thematic commentary. One of the first things I considered while writing was, does it really matter if, in a Hollywood film, the specifics of whatever regional accent from the African continent isn’t gotten accurately? And for me the answer was yes, because from a professional point of view, you owe respect to your subject matter.

An accent identifies a person, it is one of our social markers. I hear your accent, you are a New Yorker, you’re from Ogun, not from Oshun, that’s an Ogbomosho accent. It’s an identity marker. It says something of the marks the world has left on us. So if you can’t give your subject matter that respect, what does it say about how you regard that subject matter? If you wipe away someone’s accent, you are taking away an aspect of that person. If everybody talks like “theees,” then you’re sort of saying, you’re just one big homogenous bunch and there is nothing different about you guys.

Carmen McCain

So, it’s kind of the vocal equivalent of having a generic African village somewhere…

Africa Ukoh

Exactly. Like I said, it comes down to how you regard your subject matter because you wouldn’t play a Russian with an Italian accent. You’d feel stupid doing that. You may play a Russian with a Russian accent badly, but you’d still attempt to do a Russian accent. That’s the very idea of the title, 54 Silhouettes, like the continent is seen as one big shadow. A shadow has no concreteness.

Carmen McCain

There has been a lot that has happened since 2011 in Nigeria. Now we have Boko Haram. Now there are child soldiers in Nigeria. This is something I struggle with, because there is the frustration with these continuous stereotypes about Africa in the West—war, disease, corruption, like what you see in Lost, some random Yoruba guys in some “tribal” conflict that never actually happened—but there is now a war happening. How do you navigate between the realness of what is happening and the frustration with the stereotypes?

Africa Ukoh

There’s a line where Victor, the main character, says: “There is a completeness to people—good, bad, ugly, beautiful, and so much more between. Completeness. And when you deny them that, you deny them existence. You kill them.”

For me, that has always been at the core of the story and why I wrote it. Humans, we tend to do this 180 type thing. Amber Rose went to Ghana. Rick Ross came to Lagos. Amber Rose went to the slave heritage site, Rick Ross shot a music video in a slum, and the reaction is always the same: “We have rich people too, we have wealth too.” I’ve never liked that kind of zero to 180 type reaction, to just respond to a problem with the direct opposite of the problem. Someone says X people are poor and you say, oh, no, we are also wealthy. But there are more layers to our identity than just the poor and the wealthy. I guess it’s because, as a storyteller, you’re always looking to express as wide a range as form can accommodate. Marginalized people tend to react to things that way. You are put down so much that you react by lifting yourself up, but then if you lose balance you take it to an extreme and then you lose the middle, which is where a lot of growth is, which is where your complexity as a person and as a people is.

That’s essentially what Victor is struggling with—that’s what he is trying to say– moving from one extreme to another is just the same problem turned inside out. But then there’s also the question of if his approach is in itself not also extremist.

Carmen McCain

Since you wrote this, there has also been a lot of change in Hollywood. There has been the whole #Oscarssowhite thing, there’s been the #MeToo movement. Did any of that play into the revision of 54 Silhouettes? How do you think Hollywood has changed. . . or has it?

Africa Ukoh

I’ve never looked at it from the perspective of how much Hollywood has changed. I’ve always looked at it from the perspective that Africans should take responsibility for the African message. So, in the second act of the play, you have two conversations. You have Victor and the film director Larry. Then you have Victor and Sonny. Victor and Larry are the African and Western perspectives in contention, while Victor and Sonny are the African and African perspectives in contention. Structurally, it deliberately ends on Victor and Sonny. That is to say, this is more of the climactic point. This is more of the focus. This is where we should put our attention.

We have to take responsibility for ourselves. Of course, with regard to global culture and human to human respect and, for me, artistic integrity, if you pick a subject matter, you owe it due respect. And the best respect is to aim for truth. If that truth needs to be ugly, cool, just aim for truth. So, to that degree, yes, we should hold Hollywood or whoever accountable. But, primarily, we have to take charge of our portrayal. We need to keep being more directly involved in how the world is trying to interact with us.

There are awesome voices exploring African issues and identity on the global stage. Wanuri Kahiu’s Rafiki, from Kenya. Akin Omotoso’s Vaya, from a couple years back. Rungano Nyoni’s I am Not a Witch, which I utterly adore. They recently did The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives at the Arcola Theatre in London. So we do have a lot more of our own voices in the global scene, and I think we just need to keep pushing for compelling treatment of ourselves in film and theatre.

Carmen McCain

Most of the plays I’ve seen performed in Nigeria tend to be historical, and your play is quite different, although you reference Soyinka quite nicely. How do you see yourself in this Nigerian theatre tradition? How do you draw inspiration from it, and how do you depart from it?

Africa Ukoh

I’m very interested in the urban Nigerian experience. There is this misconception of what culture is—that culture is this thing removed from our daily lives, culture is this thing that should be performed, culture is this thing that stands apart from our day to day living, which, of course, isn’t the case. In some ways we, wrongly, don’t recognize urban Nigerian living as part of Nigerian culture. Yes, we have been influenced by colonialism and Western media, but we’ve taken all these things, and we’ve adapted them to a way that suits our own Nigerian sensibilities. So that’s one thing I’m trying to express in some of my plays. Of course, I have stories that are more historical or period pieces in traditional settings, but it’s also important to capture the urban Nigerian experience in an exciting way.

Any art form that doesn’t speak to the present time will lose people of the present time. In trying to excite the urban Nigerian audience, particularly young audiences, about Nigerian theatre, you also have to explore things that resonate with them. Again, we come back to the idea of a spectrum, a range and complexity to any people’s identity and expressing that artistically.

Carmen McCain

You relate theatre to urban life that young people know really well in Green White Green, which you wrote with the director Abba Makama. Both 54 and Green White Green are about creativity and the process of making art, but Green White Green kind of brings it back home. How does Green White Green engage in this responsibility to represent people’s experiences in a round sort of way, not just the extremes?

Africa Ukoh

That was always at the heart of Green White Green. It was always these four friends, secondary school graduates, and they want to make this film, and later it became, okay, why do they want to make a film? They can’t articulate it well enough to themselves because of their ages, but what they are really trying to do is figure out what being a young Nigerian means.

All humans are creative by nature. Whatever we are going through we tend to look for an artistic expression of that. And that ties to the problem of the lack of Nigerian entertainment content that is created directly for teens and kids because in the absence of that, what do kids do?

Carmen McCain

That’s true, because most of Nollywood is not directed at young people. . .

Africa Ukoh

Right. And in the absence of that, what do kids do? They do two things. One, they create something for themselves. Two, they go somewhere else, which is essentially how we of the millennial generation grew up—we went somewhere else. It does account for some of the psycho-emotional distance people feel from their culture.

To a degree we were raised by television and there’s not much indigenous content in that format that excites the attention of a Nigerian kid. So, what do kids do? They create something for themselves, one. Or they go to someone else who is speaking to them, to that child-like mind. And even that something they create for themselves is influenced by that somewhere else they went to. They turn to The Avengers, to Disney, to Voltron. Which isn’t bad in itself. It’s very healthy, very necessary, for the mind to be exposed to different cultural expressions in media. But an indigenous culture needs to be in the mix with its own aesthetics and messages that speak to its young people, or else you lose them.

Carmen McCain

As you were talking just now, I thought about how in Green White Green you have the professor character, who’s kind of pompous. But he’s still this father figure for these three boys who are looking for feedback. And then I was also thinking back to 54 Silhouettes, how you insert Death and the King’s Horseman. It’s this older voice in there that becomes, in some ways, a bit of a guide. It’s interesting that in both of these works you have the interaction between the older respected elder and the younger upcoming artist who is trying to do something else.

Africa Ukoh

I would say that is something that pulled itself out subconsciously. It wasn’t by conscious design. But like you said, especially from your first review, I started looking deeper into it and realized, oh, yeah, there is something there. It’s something that’s very important to me because it’s something I believe is missing in the Nigerian society. Part of the creative industry troubles we are going through is because there is no structure for a generational transfer of power.

Carmen McCain

In many different ways, right, politically and so on?

Africa Ukoh

Exactly. It’s a huge chasm in our social set up. My mum’s a teacher, so I’ve always loved teaching and teaching is about generational transfer. So I’ve always looked for someone to follow up on, to be their student, someone to teach and pass what I know down to.

I very quickly noticed that not only was there no structure for transfer but there was no interest in it. We are suffering the consequences today. Like you said, political platforms, artistic platforms, you see the trend. No society or industry can progress without deliberate structures to continuously develop the next generation of whatever. We’re in this place where it’s like well, if I have to put aside my ethnic prejudice, my religious prejudice, my intellectual prejudice, my social prejudice, in order for there to be progress, well, I would rather not put my prejudice aside.

Carmen McCain

That’s really interesting, because that is what you see in Green White Green. And in some ways coming from 54, you have a kind of hemispheric prejudice. You have the Hollywood prejudice against Africa, and in Green White Green, you’re bringing it back to what you see in Nigeria.

Africa Ukoh

But then that’s the thing about prejudice. Prejudice is prejudice. We’re all just dealing with different variations of the same thing—prejudice. It’s just changing forms. Hate is hate. It’s a matter of what flavor you’re tasting.

Carmen McCain

Let’s jump to Token Dead White Guy for a minute. Basically, it’s about Western coverage of Africa, right?

Africa Ukoh

Well, it could be taken that way. For me, Token Dead White Guy is about the search for a sense of value in one’s individual and collective identity in a world shaped by public perception. So it’s not really about media coverage. There is that layer or sub-layer to it, but really it’s about the valuation of one’s identity. It’s also connected to what Ernest Becker, in his book The Denial of Death, calls “immortality projects,” where a person tries to do something big, something worthwhile, something deemed meaningful as his mark on earth. But the value is placed on the scale of the thing rather than the thing itself. And the question is, is that sensible? Is that healthy?

What interested me from the media angle is questions around the difference in how the various tragedies from different parts of the world are covered. I got the idea for Token Dead White Guy in 2015 after the attack in Baga when there were like 2,000 people killed and it was a typical news story, but then two days later you have Charlie Hebdo, two guys get killed, and it’s a global tragedy.

So the question I found myself asking, the question I still struggle with today, is—is the issue that the incidents aren’t covered at all, is it that they aren’t covered enough, or is it that they aren’t covered with the same reverence as when it involves a token dead white guy? And, again, we come back to the question of African responsibility for African issues. As well as other questions: How united is the global community, in truth? To what extent should we realistically hold CNN or Al-Jazeera responsible for not giving certain communities the coverage and reverence they would give to others?

Carmen McCain

What does that say about structures of power?

Africa Ukoh

Right. What does it say about structures of power? Because at the end of the day, by its nature, power will always attend to itself. It’s a question I struggle a lot with it.

Carmen McCain

In both of your plays you have people trying to catch the attention of the West in some way either by going to Hollywood and being very frustrated by these racist roles they’ve been given, or in Token Dead White Guy where there’s one token dead white guy so now there will be global attention brought to this tragedy. So there’s something about audiences and also about structures of power. Ultimately, why are they seeking that audience?

With the question of the film industry, in my review of 54, I said “Where is Nollywood in this? Where is the Nigerian film industry? Why is Victor Chimizie trying to catch the attention of Hollywood when there are actually all these great roles he could be playing?” But then I think of Green White Green. It’s available on Netflix and film festivals abroad, right? Was there any screening in Nigeria?

Africa Ukoh

At two festivals, both in Lagos, the Lights, Camera, Action Film Festival (LCA), and the African International Film Festival (AFRIFF). I think for Nigeria it is particularly important to remember that Nigerian global interactions extend beyond the West. You have the North, which is very much in interaction with the Arab world, with the Middle East. There are interesting relations between Eastern Nigeria and China. And Nigerians are found in many places across the world.

In both plays you definitely find that attempt to find Western/global attention, but you also find something else, that is the undertone of the failure of the Nigerian/African set-up to cater for itself. And what you have is different reactions to that failure. So in 54 you have the actor saying we have to be proactive about the problem of our responsibility but you have the agent saying, “Yo, this African image thing-a-ma-jiggy is not my problem.”

Carmen McCain

“I have a proverb for you, ‘Make money’” (Sonny from 54 Silhouettes).

Africa Ukoh

Exactly. And in Token, while Notu is trying to get the attention of the world, she’s also trying to get the attention of Molambia, of the country itself.

The common reactions I get with 54, people tend to focus on the Western part and miss the undertones of the African-African conflict and the absence of structure and the struggles that stem from that. It touches on the age-old issue of having to leave Nigeria to go get recognition elsewhere before you can get recognition here, which still brings us back to the absence of structure and the problem of prejudice. You know, if I can’t climb up the economic ladder, the social ladder, the vocational ladder because of prejudices built into the system here, well, I’ll go elsewhere, where at least a structure exists to temper whatever prejudices exist there—hopefully. Whether or not that actually works, well.

Carmen McCain

Just to end out. In Green White Green, there is this hopeful ending, you see all the prejudice of the elders, and these three characters are able to defy that. They also all end up at Nigerian universities, rather than going outside. Is that just a hopeful happy ending or is that the hope for where things will end out?

Africa Ukoh

Yes, the target was a warm and hopeful ending. The intention was to have a spectacle-filled ending. Fireworks. But the budget was like “yo, chill.” We always get varying tonal feedback to 54 anytime it’s staged. For some people it ends on a very charged note and for others it’s this grave ending. How people take the ending seems to be affected by who they connected with between Victor and Sonny.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions