This feature was published before the 2019 Booker Prize shortlist was announced on 3 September 2019. It was updated afterwards and then on 14 October after Bernardine Evaristo was announced joint-winner of the prize.

The Booker Prize for Fiction is awarded annually to the best original novel written in the English language and published in the United Kingdom. Formerly known as the Booker-McConnell Prize (1961-2001) and the Man Booker Prize (2002-2019), it is widely regarded as the pre-eminent book prize in the English-speaking world. From inception, it was open only to writers from the Commonwealth of Nations, Ireland, South Africa and later Zimbabwe. It was expanded, in a badly received move, to include any novel published in English. Writers and publishers of Booker Prize-winning, -shortlisted, or even -longlisted books are often assured of a spike in book sales.

At the time of writing, three Africans—Bernardine Evaristo, Chigozie Obioma, and Oyinkan Braithwaite—are currently longlisted for the 2019 Booker Prize. In its 51-year history, four Africans have clinched the award five times, out of 41 nominations. The South African (now Australian) J. M. Coetzee is the first to win the prize twice, in 1983 for The Life and Times of Michael K, and in 1999 for Disgrace. He has been nominated six times, the most for an African. He is followed by the South African Nadine Gordimer with three (one win, two longlistings), the Nigerian Ben Okri who won on his only nomination, and the British-Nigerian Bernardine Evaristo who won, jointly, on her only nomination so far, becoming the first Black woman to do so. Authors nominated more than once include the British-Zimbabwean Doris Lessing with three (all shortlistings), the South African Andre Brink with three (two shortlistings, one longlisting), the British-South African Deborah Levy with three (two shortlistings, one longlisting), the South African Damon Galgut with two (both shortlistings), the Canadian-Ghanaian Esi Edugyan with two (both shortlistings), and the Nigerian Chigozie Obioma who is the first African to be shortlisted for their first two novels. Of the 41 total nominations, these eight multi-nominated and winning authors share 25.

The most represented African country is South Africa, with three wins out of twenty-two nominations, followed by Nigeria, with two wins out of five nominations, and Zimbabwe, with four nominations, and Ghana, with three. Writers from Morocco, Tunisia, Tanzania, Egypt, and Libya have been nominated once each.

As we did last year with the Women’s Prize for Fiction, we have put together all the books by African authors ever nominated for the Booker Prize for Fiction. Book synopses are from Amazon or the books’ publishers.

READ: 15 Authors, 19 Novels: An African History of the Women’s Prize for Fiction

1971

SHORTLIST

DORIS LESSING (UK/ZIMBABWE), BRIEFING FOR A DESCENT INTO HELL

In this ambitious novel of madness and release, Doris Lessing imagines the fantastical “inner-space” life of an amnesiac. Charles Watkins, a Professor of Classics at Cambridge University, has suffered a breakdown, confined to a mental hospital as his friends and doctors attempt to bring him back to reality. But Watkins has embarked on a tremendous pyschological adventure that takes him from a spinning raft in the Atlantic to a ruined stone city on a tropical island to an outer-space journey through singing planets. As he travels in his mind through memory and the farther reaches of imagination, his doctors try to subdue him with ever more powerful drugs in a competition for his soul.

In this provocative novel, Lessing takes us on a harrowing voyage into the rarely glimpsed territory of the inner mind.

1974

WIN

NADINE GORDIMER (SOUTH AFRICA), THE CONSERVATIONIST

Mehring is rich.

He has all the privileges and possessions that South Africa has to offer, but his possessions refuse to remain objects.

His wife, son, and mistress leave him; his foreman and workers become increasingly indifferent to his stewardship; even the land rises up, as drought, then flood, destroy his farm.

1976

SHORTLIST

ANDRE BRINK (SOUTH AFRICA), AN INSTANT IN THE WIND

The year is 1749, when the Boers ruled South Africa. And so it has come to his Baas’s final command to his Hottentot slave Adam, to flog his mother, because she refuses to prune the master’s vineyard in order to attend her own beloved mother’s funeral. And when he refuses to do so, and his Baas smashes his face with a piece of wood, Adam turns on him, and beats him almost to death. Then he flees to South Africa’s veld. There he comes to the rescue of Elizabeth, a white woman, and the only person to survive her husband’s expedition in the vast South African interior. Alone and terrified, she pleads with the runaway slave to bring her back to the Cape and her home. Adam agrees because he believes by rescuing Elizabeth, he will be awarded his own freedom.

This, then, is the stunning story of their trek together, how they find in each other their mutual need and humanity, and finally how their days together turn into an unforgettable, tender love story.

1978

SHORTLIST

ANDRE BRINK (SOUTH AFRICA), RUMORS OF RAIN

Martin Mynhardt seems invincible. Violence surrounds him, yet he remains unscathed: a woman asks him the time, then leaps in front of a train; after a mine riot, he watches hoses sweep scattered body parts off the floor.

Just before the shocking violence that brings South African apartheid to an end, Martin decides to return to the family farm for a weekend. A highly successful businessman and Afrikaans Nationalist, he hopes to sell the property to the government in a deal both highly profitable and corrupt. The moment he steps onto the farm, his plans are derailed. The repercussions of a society’s endemic violence catch up to him, and shake the relationships that frame his life.

His closest friend, a brilliant, idealistic lawyer, is sentenced to prison for his anti-apartheid “terrorist” activities ― in part because Martin refused to help him. His son, recently returned from the Angolan war, is in silent revolt against the values of his father and his nation. His mistress, Bea, an intelligent, strong-willed woman who offers Martin the hope of redemption through her own capacity for empathy, is also caught up in the gathering political storm. This is Andre Brink’s story of a society on the edge of collapse, spurred to profound self realization.

1981

SHORTLIST

DORIS LESSING (UK/ZIMBABWE), THE SIRIAN EXPERIMENTS

The third volume of Lessing’s visionary series is the first-person account of Ambien II, a female ruler of the Sirian empire who slowly realizes how sophisticated the Canopus empire is and attempts to effect a similar society.

1983

WIN

J. M. COETZEE (SOUTH AFRICA/AUSTRALIA), LIFE AND TIMES OF MICHAEL K

In a South Africa turned by war, Michael K. sets out to take his ailing mother back to her rural home. On the way there she dies, leaving him alone in an anarchic world of brutal roving armies. Imprisoned, Michael is unable to bear confinement and escapes, determined to live with dignity.

This life-affirming novel goes to the center of human experience—the need for an interior, spiritual life; for some connections to the world in which we live; and for purity of vision.

1985

SHORTLIST

DORIS LESSING (UK/ZIMBABWE), THE GOOD TERRORIST

The Good Terrorist follows Alice Mellings, a woman who transforms her home into a headquarters for a group of radicals who plan to join the IRA. As Alice struggles to bridge her ideology and her bourgeois upbringing, her companions encounter unexpected challenges in their quest to incite social change against complacency and capitalism.

With a nuanced sense of the intersections between the personal and the political, Nobel laureate Doris Lessing creates in The Good Terrorist a compelling portrait of domesticity and rebellion.

1987

SHORTLIST

CHINUA ACHEBE (NIGERIA), ANTHILLS OF THE SAVANNAH

Chris, Ikem and Beatrice are like-minded friends working under the military regime of His Excellency, the Sandhurst-educated President of Kangan. In the pressurized atmosphere of oppression and intimidation they are simply trying to live and love—and remain friends. But in a world where each day brings a new betrayal, hope is hard to cling on to.

Anthills of the Savannah, Achebe’s candid vision of contemporary African politics, is a powerful fusion of angry voices. It continues the journey that Achebe began with his earlier novels, tracing the history of modern Africa through colonialism and beyond, and is a work ultimately filled with hope.

1991

WIN

BEN OKRI (NIGERIA), THE FAMISHED ROAD

In the decade since it won the Booker Prize, Ben Okri’s The Famished Road has become a classic. Like Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children or Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, it combines brilliant narrative technique with a fresh vision to create an essential work of world literature.

The narrator, Azaro, is an abiku, a spirit child, who in the Yoruba tradition of Nigeria exists between life and death. The life he foresees for himself and the tale he tells is full of sadness and tragedy, but inexplicably he is born with a smile on his face. Nearly called back to the land of the dead, he is resurrected. But in their efforts to save their child, Azaro’s loving parents are made destitute. The tension between the land of the living, with its violence and political struggles, and the temptations of the carefree kingdom of the spirits propels this latter-day Lazarus’s story.

1992

SHORTLIST

CHRISTOPHER HOPE (SOUTH AFRICA), SERENITY HOUSE

Old Max, the genial giant of Serenity House, north London’s “Premier Eventide refuge,” might have been left to die in peace. But his son-in-law Albert, an MP with a special interest in the War Crimes Bill, has other ideas.

1994

SHORTLIST

ABDULRAZAK GURNAH (TANZANIA), PARADISE

Paradise is at once the story of an African boy’s coming of age, a tragic love story, and a tale of the corruption of traditional African patterns by European colonialism. At twelve, Yusuf, the protagonist of this twentieth-century odyssey, is sold by his father in repayment of a debt. From the simple life of rural Africa, Yusuf is thrown into the complexities of pre-colonial urban East Africa—a fascinating world in which Muslim black Africans, Christian missionaries, and Indians from the subcontinent coexist in a fragile, subtle social hierarchy.

Through the eyes of Yusuf, Gurnah depicts communities at war, trading safaris gone awry, and the universal trials of adolescence. Then, just as Yusuf begins to comprehend the choices required of him, he and everyone around him must adjust to the new reality of European colonialism. The result is a page-turning saga that covers the same territory as the novels of Isak Dinesen and William Boyd, but does so from a perspective never before available on that seldom-chronicled part of the world.

1995

SHORTLIST

JUSTIN CARTWRIGHT (SOUTH AFRICA/UK), IN EVERY FACE I MEET

Set against the background of Nelson Mandela’s release, In Every Face I Meet is the story of Anthony Northleach, and one intense, comic and horrifying day in his life.

1999

SHORTLIST

AHDAF SOUEIF (EGYPT), THE MAP OF LOVE

With her first novel, In the Eye of the Sun, Ahdaf Soueif garnered comparisons to Tolstoy, Flaubert, and George Eliot. With The Map of Love, she combines the romantic skill of the nineteenth-century novelists with a very modern sense of culture and politics—both sexual and international.

At either end of the twentieth century, two women fall in love with men outside their familiar worlds. In 1901, Anna Winterbourne, recently widowed, leaves England for Egypt, an outpost of the Empire roiling with nationalist sentiment. Far from the comfort of the British colony, she finds herself enraptured by the real Egypt and in love with Sharif Pasha al-Baroudi. Nearly a hundred years later, Isabel Parkman, a divorced American journalist and descendant of Anna and Sharif, has fallen in love with Omar al-Ghamrawi, a gifted and difficult Egyptian-American conductor with his own passionate politics. In an attempt to understand her conflicting emotions and to discover the truth behind her heritage, Isabel, too, travels to Egypt, and enlists Omar’s sister’s help in unravelling the story of Anna and Sharif’s love.

1999

WIN

J.M. COETZEE (SOUTH AFRICA), DISGRACE

At fifty-two, Professor David Lurie is divorced, filled with desire, but lacking in passion. When an affair with a student leaves him jobless, shunned by friends, and ridiculed by his ex-wife, he retreats to his daughter Lucy’s smallholding.

David’s visit becomes an extended stay as he attempts to find meaning in his one remaining relationship. Instead, an incident of unimaginable terror and violence forces father and daughter to confront their strained relationship and the equally complicated racial complexities of the new South Africa.

2001

LONGLIST

NADINE GORDIMER (SOUTH AFRICA), THE PICKUP

When Julie Summers’s car breaks down on a sleazy street in a South African city, a young Arab mechanic named Abdu comes to her aid. Their attraction to one another is fueled by different motives. Julie is in rebellion against her wealthy background and her father; Abdu, an illegal immigrant, is desperate to avoid deportation to his impoverished country.

In the course of their relationship, there are unpredictable consequences, and overwhelming emotions will overturn each one’s notion of the other. Set in the new South Africa and in an Arab village in the desert.

2002

LONGLIST

WILLIAM BOYD (UK/GHANA), ANY HUMAN HEART

William Boyd’s masterful novel tells, in a series of intimate journals, the story of Logan Mountstuart—writer, lover, art dealer, spy—as he makes his often precarious way through the twentieth century.

2003

SHORTLIST

DAMON GALGUT (SOUTH AFRICA), THE GOOD DOCTOR

Taut, spare, and compellingly readable, The Good Doctor is a brilliant literary high-wire act short enough to be devoured in one or two sittings. When Laurence Waters arrives at the small rural hospital in a South African homeland where Frank works, Frank is immediately suspicious. Everything about Laurence grates on Frank, from his smoking in their shared room, to his unfamiliar optimism about what the doctors can truly accomplish among the local population—but Laurence seems oblivious, immediately and repeatedly declaring Frank his friend despite the other’s indifference.

Frank originally came to the hospital to get his bearings after his wife left him for his best friend—but denial of the higher-level post he was promised when he came, and the disillusionment of working at a completely ineffectual hospital (it’s always deserted, an entire wing closed off and gradually being looted of any reusable equipment lacks basic supplies), has hardened him into cynical apathy—which makes Laurence’s optimism all the more irritating.

Laurence starts planning a campaign to “bring the hospital to the people,” by running clinics in nearby villages. A group of soldiers have arrived in the village, reportedly looking for holes in the border where smuggling has become rampant. Then Laurence’s African-American girlfriend Zanele, who has adopted an African name and dress, and who shares his political idealism (but not much actual intimacy, it seems) comes to visit, and Laurence and Frank host a party. During the flush of drunkenness the tensions between the staff melt away (the Cuban couple estranged by Frank having had an affair with the woman; the strained power relations between Frank and the other doctors and Tehogo, the young black African man who works as the caretaker and unlicensed nurse). But in the aftermath of the party this quickly melts away—especially when Frank goes to return the cassettes Tehogo lent him for the party, and accidentally discovers a cache of looted metal fittings from the hospital in Tehogo’s room. Finally, Laurence talks Frank into spending an evening with Zanele while he is on duty—which ends in a bizarre encounter with an apartheid-era local despot and a furtive sexual union with Zanele. Frank is understandably relieved that a few days later an appointment to see his estranged wife to sign divorce papers allows him a chance to get away.

When Frank returns, Laurence meets him by telling him everything’s changed. Laurence has ignored Frank’s wish not to report Tehogo’s theft, and in so doing has revealed that Frank was the one who discovered it. The clinic has become a huge public relations coup, raising awareness and goodwill toward the hospital though its capacities are no better than before, and everyone but Frank seems swept up in its success. And a secret Frank has been keeping from Laurence since their first day of friendship—the married poor black woman Frank has been sleeping with off and on for years, sometimes for money—comes to light, in a way, when the woman comes to Laurence at the end of the clinic to tell him she needs an abortion, and that it must be done at her home. Enjoying Laurence’s discomfort with this moral dilemma, Frank does not help with the procedure, and when he guiltily goes to check on the patient the next night, she and the shack where she lived, where he would go to meet her, are gone. Meanwhile Tehogo has more or less completely stopped coming in to work. Convinced that his affair’s husband is somehow linked to the former despot and to a rash of recent robberies because of his white car, Frank tips the colonel leading the group of soldiers—a brutal Afrikaner under whom, as a conscript, Frank had been forced to help torture black informants before the end of apartheid—as to where he thinks the despot’s encampment is hiding. Soon after, a soldier turns up with Tehogo, vitally wounded from a gunshot. As Frank tends to the wound obsessively to assuage his guilt at possibly having exposed Tehogo to the colonel, Laurence for once is completely apathetic—whether disgusted at Tehogo for being a thief and complicating his image of human perfectibility, or too distracted by the apparently more noble work of tomorrow’s second village health clinic, which seems more than ever to Frank like lip service. Frank volunteers to move Tehogo to the bigger hospital where his life can assuredly be saved, but when he wakes in the morning, Tehogo, the soldier guarding him, the bed to which he was handcuffed, and Laurence, who was on night duty, are all gone.

Soon the soldiers leave town too, and as the stultifying silence of the pre-Laurence days returns, Frank is left to make some sense of the strange almost-year of the young doctor’s presence.

LONGLIST

BARBARA TRAPIDO (UK/ SOUTH AFRICA), FRANKIE & STANKIE

Dinah and her sister Lisa are growing up in 1950s South Africa, where racial laws are tightening. They are two little girls from a dissenting liberal family. Big sister Lisa is strong and sensible, while Dinah is weedy and arty. At school, the sadistic Mrs Vaughan-Jones is providing instruction in mental arithmetic and racial prejudice. And then there’s the puzzle of lunch break. ‘Would you rather have a native girl or a koelie to make your sandwiches?’ a first-year classmate asks. But Dinah doesn’t know the answer, because it’s her dad who makes her sandwiches.

As the apparatus of repression rolls on, Dinah finds her own way. As we follow her journey through childhood and adolescence, we enter into one of the darker passages of twentieth-century history.

J. M. COETZEE (SOUTH AFRICA/AUSTRALIA), ELIZABETH COSTELLO

In Elizabeth Costello, J.M. Coetzee had once again crafted an unusual and deeply affecting tale.

Told through an ingenious series of formal addresses, Elizabeth Costello is, on the surface, the story of a woman’s life as a mother, sister, lover, and writer. Yet it is also a profound and haunting meditation on the nature of storytelling.

2004

SHORTLIST

ACHMAT DANGOR (SOUTH AFRICA), BITTER FRUIT

With the publication of Kafka’s Curse, Achmat Dangor established himself as an utterly singular voice in South African fiction. His new novel, a finalist for the Man Booker Prize and the IMPAC-Dublin Literary Award, is a clear-eyed, witty, yet deeply serious look at South Africa’s political history and its damaging legacy in the lives of those who live there.

The last time Silas Ali encountered Lieutenant Du Boise, Silas was locked in the back of a police van and the lieutenant was conducting a vicious assault on Silas’s wife, Lydia, in revenge for her husband’s participation in Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress. When Silas sees Du Boise by chance twenty years later, as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is about to deliver its report, crimes from the past erupt into the present, splintering the Alis’ fragile peace. Meanwhile, Silas and Lydia’s son, Mikey, a thoroughly contemporary young hip-hop lothario, contends in unforeseen ways with his parents’ pasts.

A harrowing story of a brittle family on the crossroads of history and a fearless skewering of the pieties of revolutionary movements, Bitter Fruit is a cautionary tale of how we do, or do not, address the past’s deepest wounds.

LONGLIST

CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE (NIGERIA), PURPLE HIBISCUS

Fifteen-year-old Kambili and her older brother Jaja lead a privileged life in Enugu, Nigeria. They live in a beautiful house, with a caring family, and attend an exclusive missionary school. They’re completely shielded from the troubles of the world. Yet, as Kambili reveals in her tender-voiced account, things are less perfect than they appear. Although her Papa is generous and well respected, he is fanatically religious and tyrannical at home—a home that is silent and suffocating.

As the country begins to fall apart under a military coup, Kambili and Jaja are sent to their aunt, a university professor outside the city, where they discover a life beyond the confines of their father’s authority. Books cram the shelves, curry and nutmeg permeate the air, and their cousins’ laughter rings throughout the house. When they return home, tensions within the family escalate, and Kambili must find the strength to keep her loved ones together.

Purple Hibiscus is an exquisite novel about the emotional turmoil of adolescence, the powerful bonds of family, and the bright promise of freedom.

2005

LONGLIST

DAN JACOBSON (SOUTH AFRICA), ALL FOR LOVE

She was a princess, the daughter of King Leopold II of the Belgians, the wife of a prince, and a familiar figure in the court of the aged Emperor, Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary.

Her lover was second lieutenant Géza Mattachich. Ten years younger than the princess, a dashing figure in his fitted tunic and shiny boots, he was an unknown, undistinguished, unmoneyed subaltern: a man of dubious origin and extravagant ambition.

Ahead of them both lay assignations, adultery, flight, the squandering of a fortune (not his; not hers either, as things worked out), a duel, imprisonment, bankruptcy, morphine, madness (or alleged madness). And, as well, a real-life heroine—in the form of canteen-worker Maria Stöger—who was no less ready than the princess and her soldier to risk all for love.

Beautifully handled, romantic, sumptuous, full of wit and a real treat to read, the action of Dan Jacobson’s All For Love moves from one end to the other of pre-First World War Europe. Constantly fusing historical fact with fiction, it elevates three extraordinary characters from the footnotes of history and puts them, along with their few friends and many enemies, at the centre of a drama that is both comic and painful, and as astonishing as it is convincing.

J. M. COETZEE (SOUTH AFRICA/AUSTRALIA), SLOW MAN

A deeply moving tale of love and mortality.

When photographer Paul Rayment loses his leg in a bicycle accident, he is forced to reexamine how he has lived his life. Through Paul’s story, Coetzee addresses questions that define us all: What does it mean to do good? What in our lives is ultimately meaningful? How do we define the place we call “home”?

In his clear and uncompromising voice, Coetzee struggles with these issues and offers a story that will dazzle the reader on every page.

2006

SHORTLIST

HISHAM MATAR (US/LIBYA), IN THE COUNTRY OF MEN

Libya, 1979. Nine-year-old Suleiman’s days are circumscribed by the narrow rituals of childhood: outings to the ruins surrounding Tripoli, games with friends played under the burning sun, exotic gifts from his father’s constant business trips abroad. But his nights have come to revolve around his mother’s increasingly disturbing bedside stories full of old family bitterness. And then one day Suleiman sees his father across the square of a busy marketplace, his face wrapped in a pair of dark sunglasses. Wasn’t he supposed to be away on business yet again? Why is he going into that strange building with the green shutters? Why did he lie?

Suleiman is soon caught up in a world he cannot hope to understand—where the sound of the telephone ringing becomes a portent of grave danger; where his mother frantically burns his father’s cherished books; where a stranger full of sinister questions sits outside in a parked car all day; where his best friend’s father can disappear overnight, next to be seen publicly interrogated on state television.

In the Country of Men is a stunning depiction of a child confronted with the private fallout of a public nightmare. But above all, it is a debut of rare insight and literary grace.

LONGLIST

NADINE GORDIMER (SOUTH AFRICA), GET A LIFE

Paul Bannerman, an ecologist in South Africa, believes he understands the trajectory of his life, with the usual markers of vocation and marriage. But when he’s diagnosed with thyroid cancer and, after surgery, prescribed treatment that will leave him radioactive, for a period a danger to others, he begins to question, as Auden wrote, “what Authority gives / existence its surprise.”

In the garden of his childhood home, where his businessman father, Adrian, and prominent civil rights lawyer mother, Lyndsay, take him in to protect his wife and child from radiation, he enters an unthinkable existence and another kind of illumination: the contradiction between the values of his work and those of his wife, Benni, an ad agency executive. His mother is transformed by the strange state of her son’s existence to face her own past. Meanwhile, projects to build a nuclear reactor and drain vital wetlands preoccupy Paul as if he were at work. By the time he is cured, both families have been changed. On his return to his home and career, his parents go to Mexico to fulfill the archaeological vocation Adrian sacrificed to support his family. The consequence of this trip is the final surprise in this extraordinary exploration of passionate individual existences.

2009

SHORTLIST

J. M. COETZEE (SOUTH AFRICA/AUSTRALIA), SUMMERTIME

Nobel Prize-winning author J. M. Coetzee’s new book follows a young biographer as he works on a book about the late writer John Coetzee. The biographer embarks on a series of interviews with people who were important to Coetzee during the period when he was “finding his feet as a writer”—in his thirties and sharing a run-down cottage in the suburbs of Cape Town with his widowed father. Their testimonies create an image of an awkward, reserved, and bookish young man who finds it difficult to connect with the people around him.

An innovative and inspired work of fiction—incisive, elegant, and often surprisingly funny—Summertime allows one of the most revered writers of our time to imagine his own life with a critical and unsparing eye.

2010

SHORTLIST

DAMON GALGUT (SOUTH AFRICA), IN A STRANGE ROOM

In this newest novel from South African writer Damon Galgut, a young loner travels across eastern Africa, Europe, and India. Unsure what he’s after, and reluctant to return home, he follows the paths of travelers he meets along the way. Treated as a lover, a follower, a guardian, each new encounter—with an enigmatic stranger, a group of careless backpackers, a woman on the verge—leads him closer to confronting his own identity. Traversing the quiet of wilderness and the frenzy of border crossings, every new direction is tinged with surmounting mourning, as he is propelled toward a tragic conclusion.

In a Strange Room is a brilliant, stylish novel of anger and compassion, longing and thwarted desire, and a hauntingly beautiful evocation of life on the road. First published in The Paris Review in three parts, one of which was selected for a National Magazine Award and another for the O. Henry Prize, In a Strange Room was shortlisted for the 2010 Man Booker Prize.

2011

SHORTLIST

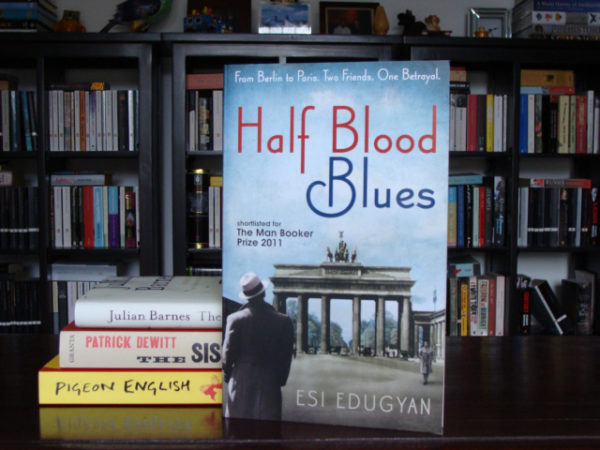

ESI EDUGYAN (CANADA/GHANA), HALF BLOOD BLUES

Berlin, 1939. The Hot Time Swingers, a popular jazz band, has been forbidden to play by the Nazis. Their young trumpet-player Hieronymus Falk, declared a musical genius by none other than Louis Armstrong, is arrested in a Paris café. He is never heard from again. He was twenty years old, a German citizen. And he was black.

Berlin, 1952. Falk is a jazz legend. Hot Time Swingers band members Sid Griffiths and Chip Jones, both African Americans from Baltimore, have appeared in a documentary about Falk. When they are invited to attend the film’s premier, Sid’s role in Falk’s fate will be questioned and the two old musicians set off on a surprising and strange journey.

From the smoky bars of pre-war Berlin to the salons of Paris, Sid leads the reader through a fascinating, little-known world as he describes the friendships, love affairs and treacheries that led to Falk’s incarceration in Sachsenhausen. Esi Edugyan’s Half-Blood Blues is a story about music and race, love and loyalty, and the sacrifices we ask of ourselves, and demand of others, in the name of art.

LONGLIST

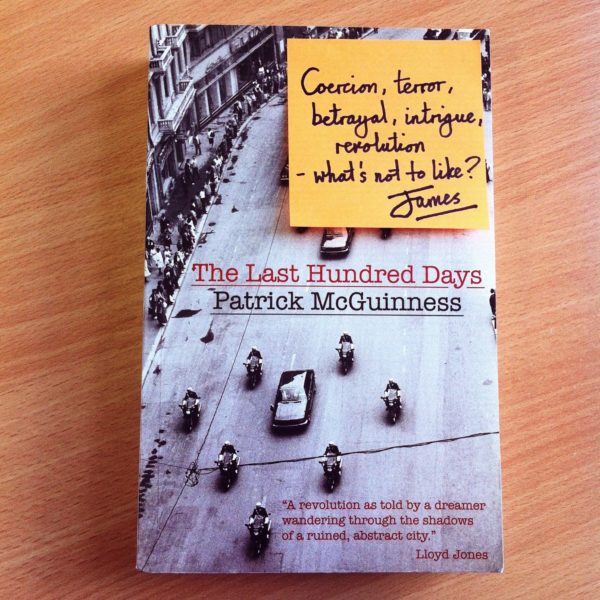

PATRICK MCGUINNESS (TUNISIA), THE LAST HUNDRED DAYS

Once the gleaming “Paris of the East,” Bucharest in 1989 is a world of corruption and paranoia, in thrall to the repressive regime of Nicolae Ceausescu. Old landmarks are falling to demolition crews, grocery shelves are empty, and informants are everywhere. Into this state of crisis, a young British man arrives to take a university post he never interviewed for. He is taken under the wing of Leo O’Heix, a colleague and master of the black market, and falls for the sleek Celia, daughter of a party apparatchik. Yet he soon learns that in this society, friendships are compromised, and loyalty is never absolute. And as the regime’s authority falters, he finds himself uncomfortably, then dangerously, close to the eye of the storm.

By turns thrilling and satirical, studded with poetry and understated revelation, The Last Hundred Days captures the commonplace terror of Cold War Eastern Europe. Patrick McGuinness’s first novel is unforgettable.

2012

SHORTLIST

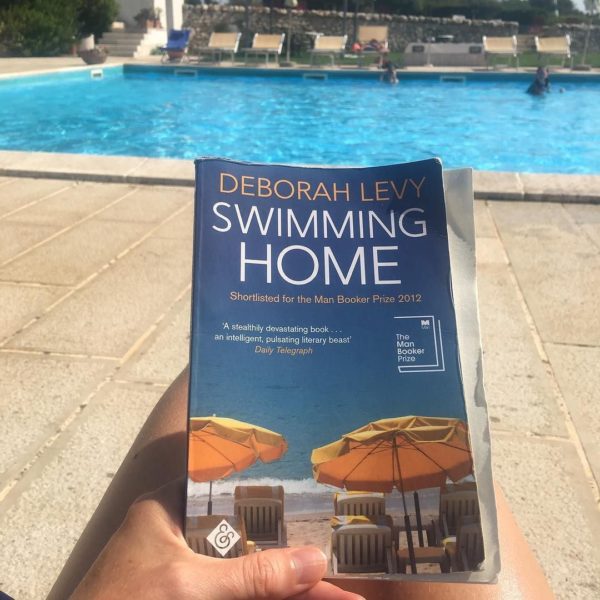

DEBORAH LEVY (UK/SOUTH AFRICA), SWIMMING HOME

As he arrives with his family at the villa in the hills above Nice, Joe sees a body in the swimming pool. But the girl is very much alive. She is Kitty Finch: a self-proclaimed botanist with green-painted fingernails, walking naked out of the water and into the heart of their holiday. Why is she there? What does she want from them all? And why does Joe’s enigmatic wife allow her to remain?

A subversively brilliant study of love, Swimming Home reveals how the most devastating secrets are the ones we keep from ourselves.

LONGLIST

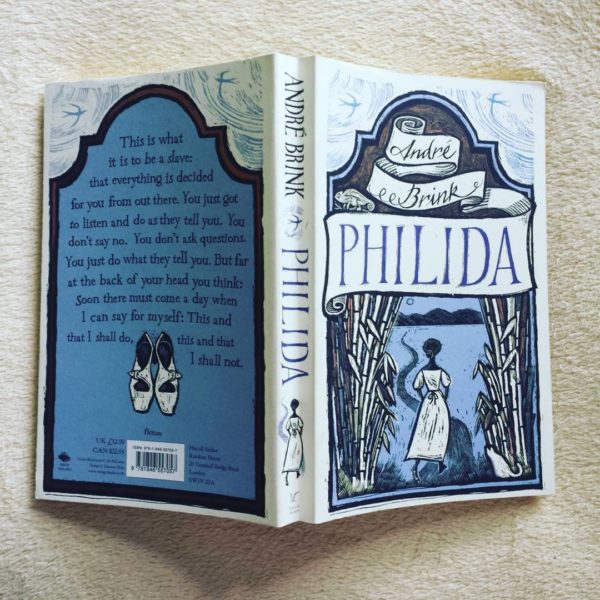

ANDRE BRINK (SOUTH AFRICA), PHILIDIA

It is 1832 in South Africa, the year before slavery is abolished and the slaves are emancipated. Philida is the mother of four children by Francois Brink, the son of her master. When Francois’s father orders him to marry a woman from a prominent Cape Town family, Francois reneges on his promise to give Philida her freedom, threatening instead to sell her to new owners in the harsh country up north.

Here is the remarkable story—based on individuals connected to the author’s family—of a fiercely independent woman who will settle for nothing and for no one. Unwilling to accept the future that lies ahead of her, Philida continues to test the limits and lodges a complaint against the Brink family. Then she sets off on a journey—from the southernmost reaches of the Cape, across a great wilderness, to the far north of the country—in order to reclaim her soul.

2013

SHORTLIST

NOVIOLET BULAWAYO (ZIMBABWE), WE NEED NEW NAMES

A remarkable literary debut; the unflinching and powerful story of a young girl’s journey out of Zimbabwe and to America.

Darling is only ten years old, and yet she must navigate a fragile and violent world. In Zimbabwe, Darling and her friends steal guavas, try to get the baby out of young Chipo’s belly, and grasp at memories of Before. Before their homes were destroyed by paramilitary policemen, before the school closed, before the fathers left for dangerous jobs abroad.

But Darling has a chance to escape: she has an aunt in America. She travels to this new land in search of America’s famous abundance only to find that her options as an immigrant are perilously few.

NoViolet Bulawayo’s debut calls to mind the great storytellers of displacement and arrival who have come before her—from Junot Diaz to Zadie Smith to J.M. Coetzee—while she tells a vivid, raw story all her own.

2015

SHORTLIST

CHIGOZIE OBIOMA (NIGERIA), THE FISHERMEN

A striking debut novel about an unforgettable childhood, by a Nigerian writer The New York Times crowned “the heir to Chinua Achebe.”

Told by nine-year-old Benjamin, the youngest of four brothers, The Fishermen is the Cain and Abel-esque story of a childhood in Nigeria, in the small town of Akure. When their father has to travel to a distant city for work, the brothers take advantage of his absence to skip school and go fishing. At the forbidden nearby river, they meet a madman who persuades the oldest of the boys that he is destined to be killed by one of his siblings. What happens next is an almost mythic event whose impact—both tragic and redemptive—will transcend the lives and imaginations of the book’s characters and readers.

Dazzling and viscerally powerful, The Fishermen is an essential novel about Nigeria, seen through the prism of one family’s destiny.

LONGLIST

LAILA LALAMI (MOROCCO/US), THE MOOR’S ACCOUNT

In these pages, Laila Lalami brings us the imagined memoirs of the first black explorer of America: Mustafa al-Zamori, called Estebanico. The slave of a Spanish conquistador, Estebanico sails for the Americas with his master, Dorantes, as part of a danger-laden expedition to Florida. Within a year, Estebanico is one of only four crew members to survive.

As he journeys across America with his Spanish companions, the Old World roles of slave and master fall away, and Estebanico remakes himself as an equal, a healer, and a remarkable storyteller. His tale illuminates the ways in which our narratives can transmigrate into history—and how storytelling can offer a chance at redemption and survival.

2016

SHORTLIST

DEBORAH LEVY (UK/SOUTH AFRICA), HOT MILK

Sofia, a young anthropologist, has spent much of her life trying to solve the mystery of her mother’s unexplainable illness. She’s frustrated with Rose and her constant complaints but utterly relieved to be called to abandon her own disappointing fledgling adult life. She and Rose travel to the searing, arid coast of southern Spain to see a famous consultant, Dr. Gomez—their very last chance—in the hope that he might cure Rose’s unpredictable limb paralysis, but Dr. Gomez has strange methods that seem to have little to do with physical medicine, and as the treatment progresses, Rose’s illness becomes increasingly baffling.

Sofia’s role as detective—tracking Rose’s symptoms in an attempt to find the secret motivation for her pain—deepens as she discovers her own desires in this transient desert community.

LONGLIST

J. M. COETZEE (SOUTH AFRICA/AUSTRALIA), THE SCHOOL DAYS OF JESUS

David is the small boy who is always asking questions. Simón and Inés take care of him in their new town Estrella. He is learning the language; he has begun to make friends. He has the big dog Bolívar to watch over him. But he’ll be seven soon and he should be at school. And so, Davíd is enrolled in the Academy of Dance. It’s here, in his new golden dancing slippers, that he learns how to call down the numbers from the sky. But it’s here too that he will make troubling discoveries about what grown-ups are capable of.

In this mesmerising allegorical tale, Coetzee deftly grapples with the big questions of growing up, of what it means to be a parent, the constant battle between intellect and emotion, and how we choose to live our lives.

2018

SHORTLIST

ESI EDUGYAN (CANADA/GHANA), WASHINGTON BLACK

George Washington Black, or “Wash,” an eleven-year-old field slave on a Barbados sugar plantation, is terrified to be chosen by his master’s brother as his manservant. To his surprise, the eccentric Christopher Wilde turns out to be a naturalist, explorer, inventor, and abolitionist. Soon Wash is initiated into a world where a flying machine can carry a man across the sky, where even a boy born in chains may embrace a life of dignity and meaning—and where two people, separated by an impossible divide, can begin to see each other as human. But when a man is killed and a bounty is placed on Wash’s head, Christopher and Wash must abandon everything.

What follows is their flight along the eastern coast of America, and, finally, to a remote outpost in the Arctic. What brings Christopher and Wash together will tear them apart, propelling Wash even further across the globe in search of his true self.

From the blistering cane fields of the Caribbean to the frozen Far North, from the earliest aquariums of London to the eerie deserts of Morocco, Washington Black tells a story of self-invention and betrayal, of love and redemption, of a world destroyed and made whole again, and asks the question, What is true freedom?

2019

JOINT WIN

BERNADINE EVARISTO (UK/NIGERIA), GIRL, WOMAN, OTHER

Girl, Woman, Other follows the lives and struggles of twelve very different characters. Mostly women, black and British, they tell the stories of their families, friends and lovers, across the country and through the years.

Joyfully polyphonic and vibrantly contemporary, this is a gloriously new kind of history, a novel of our times: celebratory, ever-dynamic and utterly irresistible.

SHORTLIST

CHIGOZIE OBIOMA (NIGERIA), AN ORCHESTRA OF MINORITIES

A contemporary twist on the Odyssey, An Orchestra of Minorities is narrated by the chi, or spirit of a young poultry farmer named Chinonso. His life is set off course when he sees a woman who is about to jump off a bridge. Horrified by her recklessness, he hurls two of his prized chickens off the bridge. The woman, Ndali, is stopped in her tracks.

Chinonso and Ndali fall in love but she is from an educated and wealthy family. When her family objects to the union on the grounds that he is not her social equal, he sells most of his possessions to attend college in Cyprus. But when he arrives in Cyprus, he discovers that he has been utterly duped by the young Nigerian who has made the arrangements for him. Penniless, homeless, we watch as he gets further and further away from his dream and from home. An Orchestra of Minorities is a heart-wrenching epic about destiny and determination.

LONGLIST

OYINKAN BRAITHWAITE (UK/NIGERIA), MY SISTER THE SERIAL KILLER

A short, darkly funny, hand grenade of a novel about a Nigerian woman whose younger sister has a very inconvenient habit of killing her boyfriends: “Femi makes three, you know. Three and they label you a serial killer.”

Korede is bitter. How could she not be? Her sister, Ayoola, is many things: the favorite child, the beautiful one, possibly sociopathic. And now Ayoola’s third boyfriend in a row is dead.

Korede’s practicality is the sisters’ saving grace. She knows the best solutions for cleaning blood, the trunk of her car is big enough for a body, and she keeps Ayoola from posting pictures of her dinner to Instagram when she should be mourning her “missing” boyfriend. Not that she gets any credit.

Korede has long been in love with a kind, handsome doctor at the hospital where she works. She dreams of the day when he will realize that she’s exactly what he needs. But when he asks Korede for Ayoola’s phone number, she must reckon with what her sister has become and how far she’s willing to go to protect her.

Sharp as nails and full of deadpan wit, Oyinkan Braithwaite’s deliciously deadly debut is as fun as it is frightening.

DEBORAH LEVY (UK/SOUTH AFRICA), THE MAN WHO SAW EVERYTHING

In 1988 Saul Adler (a narcissistic, young historian) is hit by a car on the Abbey Road. He is apparently fine; he gets up and goes to see his art student girlfriend, Jennifer Moreau. They have sex then break up, but not before she has photographed Saul crossing the same Abbey Road.

Saul leaves to study in communist East Berlin, two months before the Wall comes down. There he will encounter – significantly – both his assigned translator and his translator’s sister, who swears she has seen a jaguar prowling the city. He will fall in love and brood upon his difficult, authoritarian father. And he will befriend a hippy, Rainer, who may or may not be a Stasi agent, but will certainly return to haunt him in middle age.

Slipping slyly between time zones and leaving a spiralling trail, Deborah Levy’s electrifying The Man Who Saw Everything examines what we see and what we fail to see, the grave crime of carelessness, the weight of history and our ruinous attempts to shrug it off.

READ: 15 Authors, 19 Novels: An African History of the Women’s Prize for Fiction

For responses, please email: brittle [email protected].

CORRECTIONS: An earlier version of this feature omitted Laila Lalami’s The Moor’s Account, which was longlisted for the prize in 2015, and Deborah Levy’s The Man Who Saw Everything, longlisted in 2019.

The numbers in the title of the feature will change to accommodate new corrections.

The first introduction wrongly (predictively!) stated that Chigozie Obioma was shortlisted twice. It has now been re-corrected following his second shortlisting on 3 September.

Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Books of Not – Life through the eyes of Tambudzai - Harare.Today January 20, 2023 07:17

[…] (A history of African writers and the Booker is here). […]