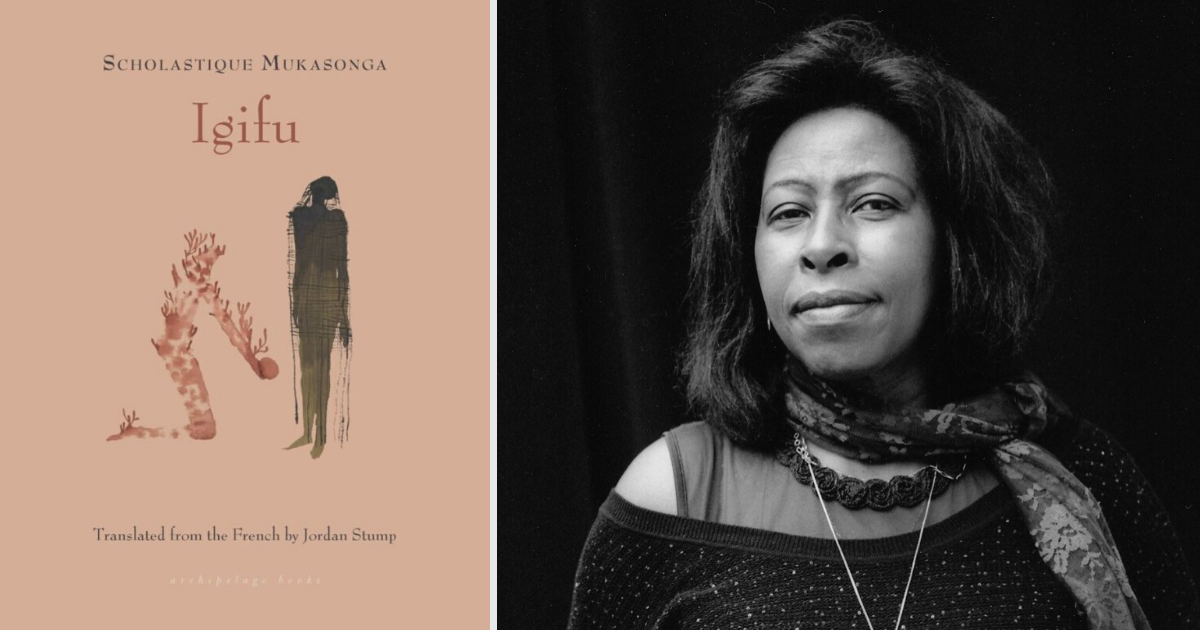

Rwandan author Scholastique Mukasonga’s Igifu was first published in French in 2010. Now, ten years later, this collection of autobiographical stories will be made available to English readers through the efforts of translator Jordan Stump. Below is a description of the book from its English publisher, Archipelago Books.

Scholastique Mukasonga’s autobiographical stories rend a glorious Rwanda from the obliterating force of recent history, conjuring the noble cows of her home or the dew-swollen grass they graze on. In the title story, five-year-old Colomba tells of a merciless overlord, hunger or igifu, gnawing away at her belly. She searches for sap at the bud of a flower, scraps of sweet potato at the foot of her parent’s bed, or a few grains of sorghum in the floor sweepings. Igifu becomes a dizzying hole in her stomach, a plunging abyss into which she falls. In a desperate act of preservation, Colomba’s mother gathers enough sorghum to whip up a nourishing porridge, bringing Colomba back to life. This elixir courses through each story, a balm to soothe the pains of those so ferociously fighting for survival.

In anticipation of the book’s release in September 2020, one of the stories in the collection, “Grief,” was published recently in The New Yorker. Read on for a preview of Mukasonga’s unique ability to “attend to how individuals’ attempts to negotiate unspeakable tragedy can lead to sad, odd, and even grimly funny situations.”

****************************

On TV, on the radio, they never called it genocide. As if that word were reserved. Too serious. Too serious for Africa. Yes, there were massacres, but there were always massacres in Africa. And these massacres were happening in a country that no one had ever heard of. A country that no one could find on a map. Tribal hatred, primitive, atavistic hatred: nothing to understand there. “Weird stuff goes on where you come from,” people would tell her.

She herself didn’t know the word, but in Kinyarwanda there was a very old term for what was happening in her homeland: gutsembatsemba, a verb, used when talking about parasites or mad dogs, things that had to be eradicated, and about Tutsis, also known as inyenzi—cockroaches—something else to be wiped out. She remembered the story her Hutu schoolmates at high school in Kigali had told her, laughing: “Someday a child will ask his mother, ‘Mama, who were those Tutsis I keep hearing about? What did they look like?,’ and the mother will answer, ‘They were nothing at all, my son. Those are just stories.’”

Nevertheless, she hadn’t lost hope. She wanted to know. Her father, her mother, her brothers, her sisters, her whole family back in Rwanda—some of them might still be alive. Maybe the slaughter had spared them for now? Maybe they’d managed to escape into exile, as she had? Her parents, on the hill, had no telephone, of course, but she called one of her brothers, who taught in Ruhengeri. The phone rang and rang. No one answered. She called her sister, who’d married a shopkeeper in Butare. A voice she’d never heard before told her, “There’s nobody here.” She called her brother in Canada. He was the eldest. If their parents were dead, then he’d be the head of the family. Perhaps he had news, perhaps he had advice, perhaps he could help her begin to face her terror. They spoke, and then they fell silent. What was there to say? From now on, they were alone.

From now on, she would be alone. She knew a few people from home, of course, friends she’d made at the university here, where she’d had to start her studies all over again, her African degrees being worthless in France. But that little part of her—the part that still tied her to those she’d left behind in Rwanda, despite the distance and the time gone by and the impossibility of rejoining them—formed a bond that grounded her identity and affirmed her will to go on. That bond would fade, and in the cold of her solitude its disappearance would leave her somehow amputated.

She felt very fragile. “I’m like an egg,” she often told herself. “One jolt and I’ll break.” She moved as sparingly as she could; she lived in slow motion. She walked as if she were seeking her way in the dark, as if at any moment she might bump into an obstacle and fall to the ground. Climbing a staircase took a tremendous effort: a great weight lay on her shoulders. She found herself counting the steps she still had to climb, clutching the bannister as if she were at the edge of an abyss, and when she reached her floor she was breathless and drained.

She tried to find an escape in mindless household tasks. Again and again, she maniacally straightened her studio apartment. Something was always where it shouldn’t be: books on the couch, shoes in the entryway, Rwandan nesting baskets untidily lined up on the shelf. She was sure she’d feel better if everything was finally where it belonged. But she was forever having to go back and start over again.

If only she had at least a photograph of her parents. She rifled through the suitcase that had come with her through all her travels. There were letters, there were notebooks filled with words, useless diplomas, even her Rwandan identity card, with the “Tutsi” stamp that she’d tried to scratch away. There was a handful of photographs of her with her girlfriends in Burundi (which they’d had taken at a photographer’s studio in the Asian district in Bujumbura, before they parted ways, so they wouldn’t forget), there were postcards from her brother in Canada, a few pages of a diary she’d quickly abandoned, but she never did find a photo of her parents.

For that, she rebuked herself bitterly. Why hadn’t she thought to ask them to have their picture taken and send her a copy? Was she a neglectful daughter? Had she forgotten them as the years went by? No, they were still there in her memory; she could call up their image anytime she liked. She sat down at her table, took her head in her hands, closed her eyes, focussed her mind, and pictured, one by one, all the faces that death might already have erased.

Then, toward the end of June, she got a letter. There was no mistaking where it had come from: the red-and-blue-bordered envelope, the exotic bird on the stamp, the clumsily written address. . . . She couldn’t bring herself to open it. She put it on her bookshelf, behind the Rwandan baskets. She pretended to forget it. There were so many more urgent and more important things to do: make dinner, iron a pair of jeans, organize her class notes. But the letter was still there, behind the baskets. Suddenly, she found herself tearing open the envelope. She pulled out a sheet of square-ruled paper, a page from a schoolchild’s notebook. She didn’t need to read the few sentences that served as an introduction to a long list of names: her father, her mother, her brothers, her sisters, her uncles, her aunts, her nephews, her nieces. . . . This was now the list of her dead, of everyone who had died far away from her, without her, and there was nothing she could do for them, not even die with them. She stared at the letter, unable to weep, and she began to think that it had been sent by the dead themselves. It was a message from the land of the dead. And this, she thought, would probably be their only grave, a column of names she didn’t even need to reread, because she knew them so well that they echoed in her head like cries of pain.

She kept the letter from her dead with her at all times. She never showed it to anyone. Whenever someone asked, “What happened to your family?,” she always answered, “They were killed, they’re all dead, every one.” When people asked how she’d heard, she told them, “I just know, that’s all. Don’t ask me anything more.” She often felt the need to touch that piece of paper. She gazed at the column of names without reading them, with no tears in her eyes, and the names filled her head with pleas that she didn’t know how to answer.

What she didn’t want to see: pictures on television, photographs in newspapers and magazines, corpses lying by roadsides, dismembered bodies, faces slashed by machetes. What she didn’t want to hear: any rumor that might summon up images of the frenzy of sex and blood that had crashed over the women, the girls, the children. . . . She wanted to protect her dead, to keep them untouched in her memory, their bodies whole and unsullied, like the saints she’d heard about at catechism, miraculously preserved from corruption.

Most of all, she didn’t want to sleep, because to fall asleep was to deliver herself to the killers. Every night they were there. They’d taken over her sleep; they were the masters of her dreams. They had no faces; they came toward her in a gray, blood-soaked throng. Or else they had just one face, an enormous face that laughed viciously as it pressed into hers, crushing her.

No, no going to sleep.

Of course, she should have wept. She owed the dead that. If she wept, she could be close to them. She imagined them waiting behind the veil of tears, nearby and unreachable. Maybe that was why she’d gone so far away, why she’d headed off into exile: so that there would be someone to weep for all those whose memory the killers had tried to erase, whose existence they’d tried to deny.

But she couldn’t weep.

…

Read a Story from the Forthcoming Translation of Scholastique Mukasonga’s Collection Igifu – Spliced Film News June 21, 2020 14:00

[…] Read more: brittlepaper.com […]