My 96 year old paternal great uncle, Nze Christopher Nnadum, in Ezeoke Nsu in Imo State, Nigeria, where I was born, was an English Literature teacher. Yet, he would rebuke anyone that spoke English around him, unapologetically. He had large bookshelves in his house and would let me stay there alone whenever he travelled. When I wrote my first published work of fiction, The Talkative Monkey and the Rabbit, which was typed with a typewriter in 2000, while I was sent to the seminary, he edited the whole thing and said: “This is written colloquially.” That was the first time I heard that word.

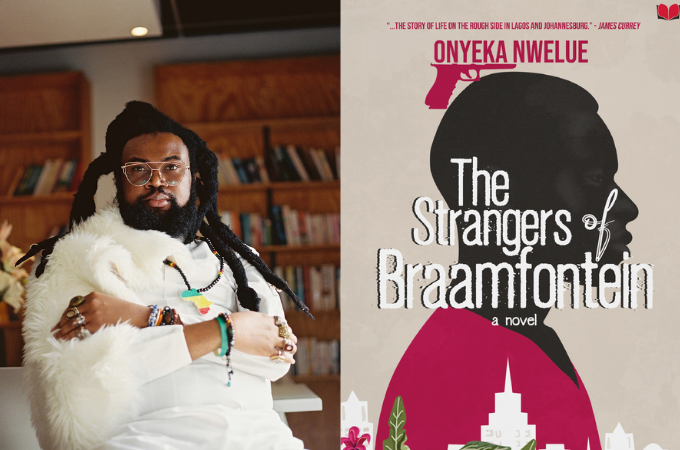

My novel The Strangers of Braamfontein is set in present day Braamfontein, a suburb of Johannesburg. As I have done with in my previous writing, the characters in the novel speak in colloquial dialects.

The book tells the story of Osas, a young and impressionable Nigerian painter, who escapes poverty and hardship in Benin City, and through the help of a travel agent, finds his way to Johannesburg. To survive, Osas must, out of necessity, live rough and spontaneously. In Braamfontein he encounters the Nigerian Janus-faced Chike, the Zimbabwean Machiavellian Chamai, the pawky Don Papi, the duplicitous Ruth, the savvy April and the fiendish Detectives Jiba and Booysen. Each encounter presents a never-ending string of adventures that lead him further into the dark and twisty underbelly of Johannesburg.

For me, writing stirs some sort of curiosity in language usage. Being a writer and an anthropologist, I spend time trying to understand people as it concerns their behaviour and the different ways in which they articulate language. When I was writing The Strangers of Braamfontein, I felt the need to recreate original characters and very unique people, so it was imperative that I used genuine dialects and voices to portray these characters and tell this story. If there was a certain way that Nigerians speak, I thought there was the need to portray that in its uniqueness; to sort of dump it in the book. This is about being conscious of cultural identifications, and paying attention to detail, and it was really important for me to do justice to that. As such, the dialect in the novel is written in a colloquial form known as Pidgin English.

I think that one major difficulty that comes with using a style that somehow deviates from mainstream writing is finding a publisher trusting enough of what you are doing. Publishing is a commercial enterprise, of course, and so there is so much to worry about where it concerns marketability. The editors and publishers in the UK and the US felt there were inconsistencies in The Strangers of Braamfontein, but what they didn’t understand was the need for me, the writer, to also apply perpetual storytelling. So I follow this character, and then I go back to his past. This could be a little bit confusing. It is like an action film or soap opera, where you go back and forth; or like playing jazz music, note by note, up and down.

Also, the difficulty of finding a publisher was not only because of the style of language. I think British publishers are quite used to the Patois in most novels from Caribbean writers published in the UK. They are not used to the voices from Africa. And I feel that only a patient person can be able to market The Strangers of Braamfontein to a British audience, even though I understand that the British literary scene is a little bit elitist, because they also want to learn new dialects, new languages, new cultures. This much could be seen from when colonialism started; the curious interest in other people, their ways of life and how far they have come in their civilization. So I am not exactly sure as to the reason, but I also think that it is its kind of narrative technique or the prose that hindered The Strangers of Braamfontein from getting published by traditional publishers in the UK; because they wouldn’t want to spend their money on what they cannot promote.

Certainly, there are different successful African and otherwise works that have been published in the vernacular in the US, the UK, and other overseas territories. There is the ground-breaking Beasts of No Nation by Uzodinma Iweala, and there is the remarkable Sozaboy by Ken Saro Wiwa, The Palmwine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola, Jagua Nana by Cyprian Ekwensi, Common Sense No Common by Chika Nwakanma, Armagedon by Jonas Dogara, Rat Palava by Sam Bright, Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien (who is not African, but he wrote slangs and people bought it into it), Valencia by Michelle Tea is also a good example.

Notwithstanding, there are also other voices like Alan Coren’s The Collected Bulletins of President Idi Amin, that are not cutting through the way that they should. But, it was published in London by Robson Books Limited.

It is in the light of this situation that Abibiman Publishing has come about. Abibiman Publishing intends to bring African literature that haven’t had any visibility in the West to Western audiences. I have just discussed with Femi Ademiluyi, author of The New Man published in 1994 and once used as recommended text for WAEC examination, and hopefully I will be able to publish it in the UK through Abibiman. We have also books by Igbo writers, like Professor Nwadike, translated into English, to be published in the UK. Abibiman hopes to bring masterpieces of African literature that have not been able to be published in the UK and the US to the forefront. That is what we are doing now; taking our destiny into our hands.

Abayomi Ayo-Kayode September 21, 2021 13:44

Dialects and colloquialism are not very remote from Literature, you hardly can read a work from the Victorian era, without coming across it, I imagine an introduction of it by an African writer, makes it a bit repulsive to a foreign publisher — like alien languages do – who is most likely to consider the pool into which the work goes.