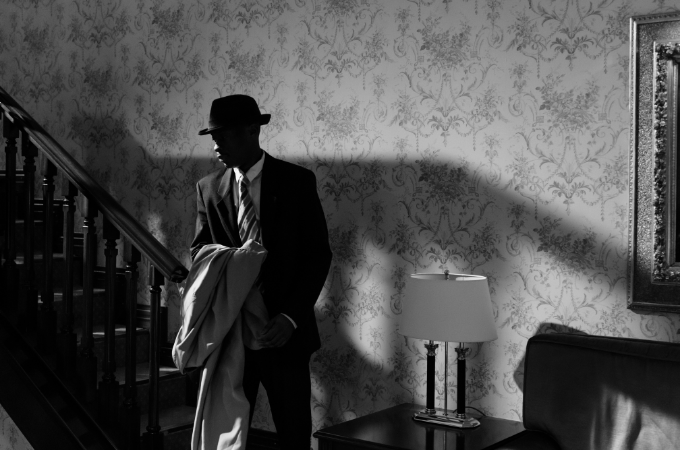

In the early morning of November 4th 1993, my father had his life taken inside our home. Not by the seven men all dressed in Silver Suits, not the ones who came before them speaking fast and all carrying briefcases, not even the watery one with the gun and the bright letter in his hand. It was all red and had no more than 10 words written on it, but I couldn’t read it and yet, I could see that somehow, my father had got himself in some real fucking trouble. What kind? Then, I didn’t know. This one spell I saw him standing there, outside by the garage, surrounded, before I could say anything, one of the men interrupted.

“This case, Thabo, this bloody case!” the man kept repeating, looking up and down our house like he’d been taught to.

It wasn’t the first time I’d heard my parents talking about it, this case. Mostly arguments raised by my ever caring and complaining mother, agonized by the large amount of time father spent on it, his vision of how it would go, its ending, the support, at least once he skewed it out of secrecy.

“Thabo! Thabo, this case will get you killed, please sthandwa sam, please, look at what it’s doing to you!”

“My love, what is right is right,” he’d casually say.

‘Suka maan!” was her mild response.

They’d go on and on but, eventually, they’d find common ground. It never came easy and, for the most part it depended on one of them deciding to let it go. In the end, her words came to be true because the case really did lead to the loss of his life. It really did lead to her having to raise me without him. The anger his absence formed is hard to explain. On certain nights, I’d just hear my mother crying out loud with her door locked. Then in the morning, it would be like nothing ever happened

My father died a rare and respected lawyer, for a wide range of reasons I see necessary to mention. Upstanding, never mincing his words, he said he knew the law like he knew himself. His problems started when I was 13, in ‘89 when he was banned from taking on cases outside the Eastern Cape. Why? The news and the government held this unusual narrative. They were singing the name song: Thabo Tsugile is a Terrorist! A real problem to the future of this country. Bullshit like that.

In my eyes, it truly all began when he started representing workers in the mining industry, eGoli. The miners, Thixo! They play a significant role in this story. During that violent time, trade unions for workers were allowed and, the boss was no longer the only one doing all the talking. Most of the miners were my father’s friends, real close. Given the demand for diggers during that period, many left the Eastern Cape, believing eGoli would look a lot like the end of the rainbow. Far from it, many were dying, and the rest were grumpy about the working conditions. They’d cry that the shafts were shaky, suicidal, and there was no guarantee you’d come up if you went down. For what? Just to keep a pulse, father would say.

No benefits, no insurance, if you died today you’d be replaced tomorrow. The wheel was kept spinning by desperation. What else really could make a man work down there? Literally, pulling out millions and millions from the earth, and not having anything to show for it. I mean day in and day out. Until one day, 8 miners on duty were buried and killed underground, the story made the whole country wake up to what was really happening, no less the wives and kids left behind. Although the news slanted the sum of those men’s sacrifices, my father didn’t need to hear any more to leave us and take off to save the day.

Soon after meeting with the families, not even a day later, the radio started reporting about a lawyer named Thabo Tsugile who’d be taking on this big mining conglomerate called Ivory Steel. Essentially, this was a lawsuit against one of the largest companies in Africa, who for the most part was known to have bad deeds and still get off scot-free. To their own detriment, they also took my father’s lack of experience at the time to be some sort of weakness, out of his depth, and they couldn’t see it. Not the hunger, not the fire inside him, and of course, the point he wanted to see proven.

The company denied any acts of misconduct, no wrongdoing, blaming the 8 deaths squarely on the deceased. Negligence, they said, otherwise why aren’t others dying? That was their argument. A lousy one when you consider that a majority of their remaining workers were willing to testify against this. Before the trial, many were even willing to lose their jobs, their pride at home, in exchange for any justice that could be reclaimed. In exchange for any peace that could be attained, if not for them, then at least for those broken families.

The trial lasted two heated full weeks before a settlement was reached. The company agreed in benefit of not only the families but, for the workers who’d be carrying on risking their lives in those mines. They declared to introduce new cautionary methods in protection of their workers, they agreed to an overdue wage increase, and more importantly, the widows received money, the most given in a company case. So naturally, more and more people wanted to know about Thabo Tsugile. Where is he from? Where did he study? What are his political links? Is he siding with the socialists?

The regime was paranoid, it was agitated, I mean dead curious, mostly because they thought they knew all the problems in the country worth knowing. It goes without saying that their first guess was that he was in the ANC. Surely, there must be bonds, he went to Fort Hare. Well, there wasn’t. Apart from meetings he’d attended here in PE – Mandela, Tambo – they didn’t know my father from a bar of soap. Only the government strongly believed they did, and this only increased the attention on his life more than he must’ve wanted. I can only guess.

What time then told is a traumatic story, not just for me but for my mother as well. The period I’m referring to is when my father started getting the idea of taking the government to court. It tainted his each and every word, the stamp in all the letters he was sending. Whenever I read them today, I halfway feel the emotion behind what he was trying to portray. As a child the picture was vague, and all I saw was just absence. Running away from responsibility, the typical narrative of abandonment, they say it can last a lifetime if you can sound your inaction, composure, for filling that void or, in trying to fine-tune the detachment.

In ’85, the National Party put out a statement on ‘wanting’ Mandela’s release, the returning of exiles, prosperity, peace, and all that lovely stuff. A complete turnaround from their initial standing of no negotiating with terrorists. No reaching out for settlements, nothing that gives out weakness as evidence. Anyway, the resistance by then had already grown legs; it was running, in and outside the country. The urgency? Freedom is coming, one way or another.

“Them just handing this country over? A dream sthandwa sam, please, vuka – wake up.” He’d usually say this to get mama worked up, and then carry on digging through those large books like he would find gold in there. Calls kept coming in from the miners in eGoli. Concerned that Thabo had conceded to this ban, they’d repeatedly ask why he’s not fighting this legally like he usually does.

“Thabo, ungalinge uthi us’ncamile kwel’cala mntakwethu – don’t say you’ve given up on us this side,” I heard a friend of his say on the phone.

Based on the ANC’s allure, much was desired by the masses in respect to a future that they represented, even more because of their honeyed talks on nationalising the country’s mines. Most didn’t have a clue how much was being made down there, what people did know though, was that they were making a lot. The miners had a good idea about things, firstly for those living in strained conditions, bucket systems, facing indirect afflictions. Then secondly, for the unborn who wouldn’t need to grow within the ebb & flow of Capitalistic traditions.

“Soze Tshangisa, I wish I could tell you more Mfowethu but all I can say is this: it will be for the benefit of our brothers and sisters.”

The miners once said they had more faith in him than they did in themselves. For my mother, as much she loved him, it was a different story. She always hoped it could be someone else that they called on for help. A large part of her was hoping he’d just focus on acquiring us some wealth. The bag. Sounds selfish, until you know, or better yet understand where the woman was coming from. Literally, from the beginning of her upbringing up to birthing me, life was mired in struggle. Covered in hurdles and decorated by sacrifice. Her family survived solely on selling wood, and she had 6 of her 12 siblings sleeping in the same room. So naturally, her main intention was moulding a life that’s better than the one she grew up in. Never mind her own strict father who’d beat them if ever a friend came by while they were chopping.

“Benditheni nge chomi hee?! – what did I say about friends huh?” This question, she says, always preceded the belt. Apart from him, she constantly maintained her focus on school, keeping decent grades, and now and then daydreaming of being a teacher. Acting out the future with her bag, her chalk, and her siblings as her pupils. Her passion, her calling, she felt would be jeopardized by political affiliations like her brothers, especially in a place as turbulent as Cradock during Apartheid. Matthew Goniwe and the youth there could see nothing else. Besides, for the men, sitting in a classroom really sounded fruitless when reality was providing different tests in the form of bullets and teargas. Regardless, after passing Matric she enrolled at Fort Hare to do her B. Ed. This is where she met my father, that’s where they fell in love.

In the beginning, coming from different backgrounds, they were some kind of north and south, inside and out, with polar postures, but essentially both wanted to play their part. They held the same stance. Both wanted to bring back what had definitely been lost. Love. My father on the other hand doing law carried the charisma and the compassion toward his cause in a way that gripped onto mother’s heart without him really trying. As he’d say, “ndandi ndim phana, ndamgqiba nje ngalonto – I was myself there, and that’s what got her,” and then they’d both laugh.

Given the dominance of whites in the law industry, which they wrote, some blacks studying in that field held a pretentious persona meant to emulate all that they’d seen, attire and all. “But hayi yhuuu not uThabo!” she always said. “I could see that eyyy this one, he’s trouble! But he’s real maan.” At Fort Hare my father involved himself in many student affairs, political agendas, he came close to being expelled twice, and his name started to become known for the wrong reasons. Infamy, you know, the rebel’s price.

At the crossroads of wanting to mould young minds for the better and him, pursuing law to have his hand in politics, both realized that one has something the other doesn’t. A void that them being together could fill. And for a while, it did. They got married, moved to then Port Elizabeth, and then had me. I wish I could end it there. Happily ever after. No. The whole inspiration behind getting his degree was to take on every single injustice, and this country was filled with them. At the time that he decided he wanted his firm, there weren’t too many others doing this. “Can you believe it, my love? Heee, it was easier for me to get that degree than it was for those dogs to allow me my own practice. “

Charging far less than what white firms were, as well as operating in the township of New Brighton, the cases now quickly started coming in. Most of them labour disputes such as the large one in Uitenhage in ‘88 involving Boxwagon and its workers. A typical story based on exploitation, simple explanations given by bosses to labour when it came to confrontation and then, capitalizing on their desperations.

Then one day, a call comes in from Tshangisa, the one person who knew how to bring the fire out of my father. They went to high school together. He’s also the one that convinced him to go to Johannesburg, to let go of all the work he was doing in the Eastern Cape. For what? “Umgwebo – the judgement. That’s what they called their struggle there, and more importantly, they knew it was something that they could change.

The idea for this case came to him while he was there. “What if the people take the entire government to court, not just individuals? For all its murdering unpunished, the massacres, June 16’s, for the illegal detainment of millions, for the unjust laws that were passed without native content since 1916, to the gross exploitation of the country’s resources?” His own conscience told him immediately that the thought was irrational, impossible, and way far out of his depths. “Come on, can the people possibly win against the state? Of course, they can. All we need is proof, solid, proof.” This is all he needed to convince himself.

Evidence, truth, yeah, in court that can go beyond reasonable doubt. Even so, the state had immense power to buy out, take out, and make up anything or anyone in order to make sure that things went as planned. Like most of the miners he’d represented, my father acted to be in support of the negotiations, CODESA, meanwhile gathering material from kinfolks whose loved ones were taken by the police to never return, collecting figures on how much was being made on mineral exports, and some crucial confessions from former white policemen who said they’d be willing to testify to some of this, incredibly.

In no way could my father do this alone, I mean not even in his grandest, outlandish, courtside dreams. He knew he’d need help, and this would be the contrast to his mystery, drafting a team of 37 black lawyers that were willing to go to trial with him against the state. News like that found its way to authority dead fast. Plus, he wouldn’t be paying them, yet still convincing them to go pro bono for a situation that could probably finish their careers. That’s if they lost. This was the odds. Sure, so obviously, no levelheaded attorney jumped at his plea. The number eventually led to a team of 23, rather than the beautiful number he had visualized up in his sleep.

Make no mistake; the ones who did agree were very eager, smart, the likes of Sizwe Fenyana, who worked on the conviction of 11 farmers in the Free State, who’d also decided to open his own firm in Johannesburg. The trailblazing Moses ‘Lucky’ Dube, who took on SABC and won two years earlier for defamation, and the overspoken Peter Mgabile, who graduated law at Fort Hare. My father believing that he could keep Peter quiet was maybe his biggest mistake. The government was watching him closely for years, he just didn’t know. Peter openly denounced negotiations, he was a branded communist, and so, trouble was wherever he was.

They agreed to meet every night at an abandoned, broken-down mining hostel near Thuthuka, a place nobody would know, not even their families. This is how it would go, during the day they’d carry on living their normal lives, causing no suspicion, and by all means, staying out of the news. All they’d do is land themselves in jail if they didn’t. The plan was simple: each lawyer had his own sector of the scheme to cover. Impressively, for two months they were able to discreetly pull these meetings off, compiling cases that magnified an absence of justice, contacting witnesses in the homelands by the thousands, collecting documents that reflect the government’s corrupt relationship with corporations, their role in the evading of taxes, official statements, the works.

Now going into the third month, the police suspected some suspicious activity with Advocate Mgabile, the other lawyers were less known so they managed to evade attention. Peter on the other hand was found to be looking into the matter of a black reporter from Cape Town who worked for the Langa Times. Allegedly he killed himself on the brink of a large, nasty discovery implicating Basic Bank for directly sponsoring the government with funds to buy arms, which would no doubt kill its own people. Eight years later, someone is sniffing around about it, and of all people, it’s a lawyer on their list.

“My god, what does this bloody kaffir want?” I imagine them asking themselves

at the special unit. “Vat die nonsense en trek hom hierso – fetch him and bring him here.” The police knew where Peter lived, they knew that his wife went to church every Saturday, so, finding him wouldn’t be that difficult. And indeed, they did in broad daylight walking out of a superstore near his home. They took him in for questioning, did a thorough interrogation with their torture techniques, and vividly expressed to him that he’d never ever see his son again. No guessing on whether they got him to talk. Some say he sang on that very same day, and others say he was kept in a dark room for two days. The sort of darkness that can make insanity start shouting your name. Less popular gossip in our town says that he was working with them all along. Not true. Peter never wanted to go crazy, or even lose his son, at least not for something that he didn’t see as his.

He gave up every single attorney involved, the length and depth of their operation, and when they were planning to go public. But having heard of Peter’s capture, most of them knew they’d surely been compromised. They fled to places like Lusaka, Tanganyika, and Harare. But whereas my father came home, sadly the talented Mr Dube didn’t. News came of a twisted and bizarre car accident which apparently, immediately, took his life only a week after Peter’s confession.

Back home in the Eastern Cape, banned, depressed, and feeling a large lack of purpose, Tshangisa’s call stirred that fire in him once again, bringing back the desire to carry on even though he knew that this time it would have to be on his own. With a new approach, a new tandem, his plan would be to focus on one individual rather than the entire government. Other than that, he never shared anything more about this new case. Not with me, not even his wife. This was the biggest reason why she kept begging him to let it go, also why they couldn’t stop fighting. “Sthandwa sam, uyayqonda ingxaki os’faka kuyo ngalento? – My love, do you understand the danger you’re putting us under by continuing this case?”

“Sthandwa, what must happen is going to happen.”

In the month of October, his last month alive, we had more visits than a prison. I realize now that he was actually under house arrest. And among those who came before his death were members of the government’s special unit, sent strictly to intimidate and extract information. Some of them businessmen offering my father lofty positions once the ban was lifted, others we had no idea who they were. But, in true Art of War combat style, veiled rivalry, the person that would kill my father would of course be the last one we expected.

To the point that as soon as we saw him come in, death immediately left our minds. We waved away any warning signs. We basically left my father alone with his killer, and then, like any other day, we went back to sleep. The calm in my mother’s face told me not to worry, even though I knew that 5 am is a disturbing time to visit. Before my eyes closed, I could hear them laughing, reminiscing, the sound of a non-pretentious, factual bond coming from a distance in the living room. When we woke up, the front door was open and my father was gone, a nightmarish memory to remember through any lens. It was easy to see that he was poisoned. I doubt I’ll ever forget how long my mother tried to wake him up. Screaming for relief, still believing that maybe he’s in some deep sleep. Then word came, to let us know that the miner was compensated to make my father unavailable. There was no place for him in the New South Africa.

A few days later, the police called to tell us that they had nothing on the miner to actually pin him for the murder, they had no choice but to let him go. My father’s case never made it to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, as widely held as he was. All that was given was inclusion in that list of celebratory funerals, expensive memorials, paid for murals, grants from foundations, plural. A small exchange honestly, to pay for that case which never made it to court against the State. All his papers were seized, the leads, confessions, this new subject he said he’d be focusing on. The only thing the investigators never took is the note that was left in my drawer.

Noba wena awuyazi, mna ndyayazi ba uzode uyazi, zuqhubeke.

Even if you don’t know, I know, that eventually you’ll also know, so, carry on.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions