The second she learned that Mr Okafor’s mother had just arrived Kaduna from the village, Georgiana rushed down to the fruit market beside Station Roundabout to get her a large ball of watermelon, some oranges, cucumbers and apples. The following morning, she skipped class in order to accompany Mr. Okafor as he drove his aged mother to the ear specialist in the heart of town. At some point while they waited for their turn and the mother complained of the Kaduna cold freezing her neck and feet, Georgiana dashed off to the flea market in the other part of town to get her a polo neck and a pair of thick stockings.

Okafor didn’t bother to explain to his mother that Georgiana was just a friend and that their relationship was non-sexual. He knew that his mother would immediately dislike Georgiana if she knew that until a few months ago, the twenty-four-year-old used to be a sex worker in the brothel outside of town. He knew that his mother wouldn’t understand Georgiana’s past. He was sure that like many other people, his mother graded sin in some order of magnitude, and that prostitution weighed heavier than lying or stealing and only lighter than murder.

Days later, Georgiana would also join Mr Okafor to see his mother off at the motor park. After she handed the old woman a shopping bag containing large tins of powdered milk and chocolate drink, the latter would hug her and call her “my daughter,” and beg her to take good care of Mr. Okafor.

“It’s like he only eats noodles or bread,” the mother would complain. “He should be eating proper food more often.”

“I’ll make sure he eats better,” Georgiana would smile, “I promise.”

One game Georgiana liked to play was to imagine old age coming upon her so rapidly while she was still in her mid-20s. She would imagine turning wrinkle-skinned, poor-sighted, grey-haired, stooping, toothless and frail. But whenever she came to the point of picturing herself lying on her dying bed, she would quickly snap out from that stream of negative thought, because she had been told that thoughts had a way of manifesting. But without any doubt, she had been stretching herself to breaking point lately. When she was not attending to clients at her beauty shop, she was studying her online course materials. And now she had added to her load of tasks coming over to Okafor’s every weekend to make him a pot of stew and a pot of rice.

This Saturday, after Georgiana had finished cooking Okafor a pot of soup which should last him till the next weekend, curiosity drove her to push open his bedroom door and to peep in. Because the burgundy curtain on the window was too thick to let in light, she had to grope the wall beside the door until she found the switch and flooded the room in a dull orange light. She shuffled across the room to the bedside table and found a photo album in the lower drawer which was unlocked. Sitting on the edge of the bed, she flipped through the pictures until she came to a row of related shots, of Okafor and a certain girl.

In one of the photos, the two stood side by side with their arms around each other’s shoulders. In another one, the girl was buried in his embrace so that only a side of her face showed. The third one had Okafor smiling sheepishly while the girl held his left earlobe in between her teeth. They looked happy and so much in love with each other. As Georgiana kept flipping through the pictures of Okafor and the pretty girl, she felt a surge of jealousy rise from her lower abdomen up to her throat. That moment, it struck her that she had never been in a serious relationship; all her past encounters during her days of sex work had been transactional; she had never been loved by any man with such intensity as she could see in Okafor’s eyes. How lucky this girl in the pictures must be, to be loved by such a good fellow as Okafor. How protected she must feel to be so wrapped in such strong, muscular arms.

The silly idea came in whispers so delightful she couldn’t rebuke it. She began to wonder what Okafor smelt like. Although they had stood close to each other on several occasions and had even shook hands, she had never tried to catch a whiff of his scent. Disapprovingly, and yet helplessly, she left the bed and marched to the slightly opened wardrobe and scanned the shirts on the hangers until she picked out one that she was sure he had not washed after wearing. She rolled it into a ball and pressed it hard on her nose and filled her lungs with that smell of musk mixed with body lotion and perfume. She took off her blouse and put on the shirt just to feel him around her body. When she had buttoned it up to the neck, she returned to the bed and lay on her back and closed her eyes. And first, she wrapped both arms around herself imagining they were Okafor’s arms, and then she released her left hand and let it wander down.

When she was done cooking, she served herself in a hollow ceramic bowl and shuffled to the sitting room where she slumped onto the three-sitter couch to watch Moana. Even though Georgiana had seen this cartoon more than five times before now, her interest in it never waned. It was not the soundtracks that interested her that much. It wasn’t even the captivating storyline. Rather, it was the personality of Moana: her resoluteness; her focus and her rebelliousness. It was from watching Moana that Georgiana learned to mumble to herself: “I am Georgiana of the human race. I will pilot my destiny according to my will. I will complete my course and finish strong.”

At the point where Moana despaired and threw the gemstone into the ocean, Georgiana’s vision began to blur. She suspected that smoke from cooking had entered her eyes. She rushed to the toilet and washed her eyes with clean water and then leaned close to the mirror above the sink to study her eyes. Keeping her head still, she gazed from the extreme left to the extreme right, from the ceiling to the floor, and then she rolled her eyeballs in their sockets until she thought she heard them gurgle. A few minutes after she returned to the TV, a dull hum began to drone inside her ears followed shortly by a mild ache which slowly spread all over her forehead and then down to her eyes. When she realised that the pain intensified when she looked at bright objects, she turned off the TV. She couldn’t even fall asleep. It was as if the headache had disabled her sleep-inducing mechanism. It was as if she was not permitted any reprieve in this agony. However, she didn’t stop mumbling prayers, asking God to forgive her for her past and most recent sins. Most of all, she prayed that she didn’t die from this pain. Nothing frightened Georgiana more than the thought of having to die when she had not even lived life; when she had not gotten to visit home again from which she ran away five years ago; when she had not rounded off her university programme; when she had not gotten to marry and have a child; when she had not gotten to set up an advocacy body that should help rehabilitate teenage sex workers.

She couldn’t say for how long she remained somewhere a little above sleep until Okafor returned. “Terrible headache,” Georgiana sobbed as Okafor sat beside her and laid the back of his left hand on her forehead. Although it was not as hot as he had expected it, the veins that crossed the hairline and disappeared somewhere around her brows bulged and pulsated. From the way she described what she felt, Okafor guessed it had to be migraine. He hurried out to the pharmacy down the street. An hour after she took the tablets, she felt better. Still, her head remained saturated with pain the way a shoreline remained turgid with water even after the waves had receded. When she opened her eyes and peeped at the TV and saw that Okafor was watching Notting Hill, she sat up, knowing that the movie would be interesting because she had seen this same actor, Hugh Grant, in Four Weddings and a Funeral.

The more she felt relieved, the more she felt embarrassed over the way she had melted in a sob when Okafor came back and sat beside her. Still, she wished he had bent over and kissed her teary cheeks. Or something like that. Also, she wished she could tell what to make of the tender way he had placed his hand on her forehead and the soft tone with which he had spoken to her. Was that how he would have treated any other person? Or could it be that he also felt something for her the same way she felt for him? Could it be that he liked her, or even loved her, but was being careful? Did she have to encourage him? Georgiana was confused.

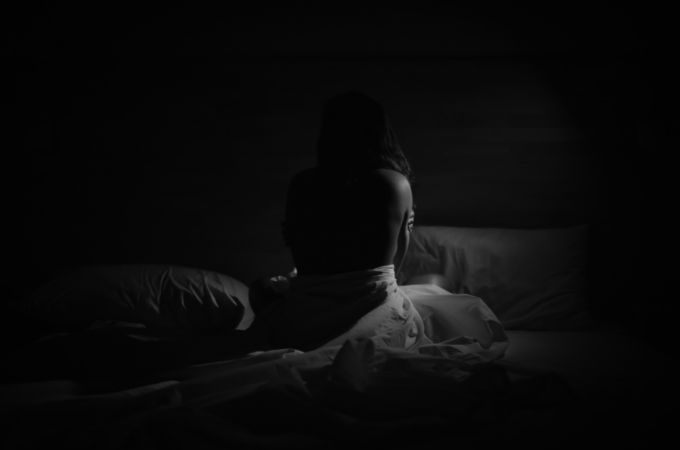

The movie ended at about past ten. Okafor told her she could stay over if it was okay with her. “It’s okay,” she said, thrilled by the thought of having to spend the night in his place for the first time. When he asked her to go to the bedroom, she lied that she was feeling too dizzy to even stand on her feet. He lifted her in his arms and marched to the bedroom but, to her disappointment, he lowered her onto the bed and walked away to sleep on the couch in the sitting room.

Their fusion didn’t occur with lightning rapidity. Rather, it played out like a pot of water set on a low-burning stove. At first, Okafor ensured that he was properly dressed whenever Georgiana was around. But with time, it began to feel normal to come out to the sitting room in singlets and shorts to watch TV with her. And then, it became normal to sneak out of the bathroom to the kitchen for some hot water with a towel around his waist. And when that day finally came, it didn’t play out as she was used to seeing in movies. There was no background music and the two of them didn’t stare into each other’s eyes for minutes before locking lips. He had just stepped out of the bathroom after a warm bath, grumbling about an itch at the middle of his back where his hand couldn’t get to. He had rushed into the kitchen where she was busy slicing a bowl of tomatoes. She had rinsed her hands at the sink and had taken a look at the middle of his yellow back where pink dots had formed a small ring.

“Ringworm,” she had mumbled.

“Ringworm!” he growled, “of all skin diseases. I hate ringworm.”

She had chuckled and had assured him that it wasn’t that bad, since there was just one of it on the whole of his back. She had scratched the embossed spots with the tip of her nail and stroked it with the tip of her index finger, imagining it to be braille. Even with her eyes closed, the tip of her finger was still able to make out something that felt like an O, a Q or a G. And because he had kept standing there after she had told him what it was, her hand had wandered from the ringworm to other parts of his broad back. And then, as if her feet suddenly lost their firmness, her head had fallen on his back and her arms had flung around him to stroke his hairy chest down to his navel.

She had sobbed throughout the time they remained bound in arms, in lips and in hips. It hadn’t been because the exercise was rough or painful. Far from it. Rather, she had sobbed because it had been the tenderest sex she had had. She had sobbed because she finally understood why it was referred to as ‘love-making’. She had felt truly loved for the first time in her life. She had sensed love and care in his eyes, in his touch, in his kisses, in his thrusts.

Photo by Ahmed Ashhaadh on Unsplash

Zino Asalor November 05, 2022 14:47

Enjoyed this. Good writing