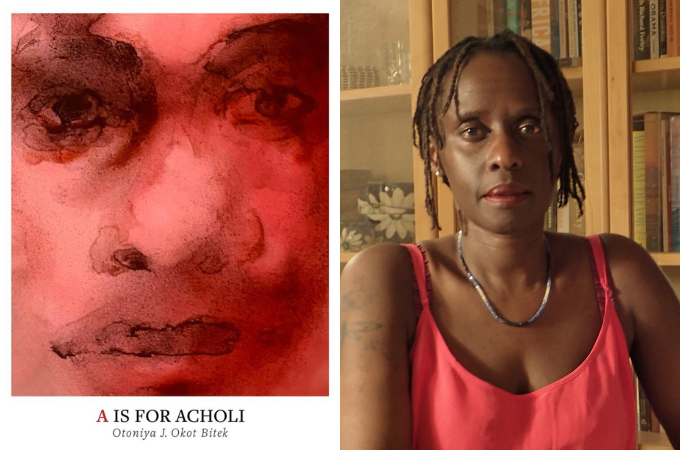

Reading A is for Acholi is an exercise in interaction. The highly experimental collection pushes the reader to reach for the depth of each poem, rather than have a cursory look at the text. In a way, reading the book reminded me of the communal and participatory way of life in many African societies— farm work, raising children, and even eating. Otoniya J. Okot Bitek achieves this by breaking and remaking language but also pushing the limits of poetic forms.

In the first section, “An Alphabet for the unsettled” which has the sub-section “An Acholi alphabet,” Bitek flips the standard way in which we use footnotes. The footnoted text is not a by-the-way piece of additional information, but part of the poem. It gives the poem emphasis and stretches its meaning. For instance, in a poem about identity, Bitek footnotes just one word—nonsense—to reject the definition of citizenship, nationality, or tribe. With one word, Bitek lays claim on all three identities:

N is for not Acholi14 enough

N is for not British enough

N is for not Canadian enough

14 Nonsense

Bitek, an Acholi from northern Uganda, writes about home, race, and racism, as well as belonging and identity. She articulates some of these subjects in the lyrical introductory note [excerpt]:

I’ve been thinking diaspora is & is not

the us of home & how & where we’re enough &

how this nation demands &

that nation extracts &

that other nation seeks but does not want us.

to say hello ki leb Acholi

one might ask quite literally i tye

are you there

do you exist

are you

in response we might say a tye

a tye ma ber

I’m here I exist I’m good I’m fine I exist well

There’s a longing for what was left and lost in her home country and a constant struggle to feel part of her other home, Canada:

S is for Acholi19

S is for the gates of unfreedoms

S is for gestures limited to the moneyed

19Suspect

Whenever we heard sirens during the graveyard shift my co-worker would say

Duck Julie

They are coming for you

The second section, “A dictionary for un/settling” introduces shape/form poems, rictameters and images. This section draws the involvement of the reader’s sense of sight as they navigate the poems. The poem “Ah, well” for instance is a series of punctuation signs—commas, quotation marks, and full stops for half of the page before it ends with “Ah, well,/it’s all over now.” The poem reads like an exhale, a typical sigh of relief. A similar format is applied to the poem “How she talked.” In between the punctuation marks, sits the line “she talked like a fury”—a line potent and heavy with meaning but it also builds on the collection’s many tones—fury being one of them.

Bitek also appears keenly interested in language and uses it to claim her Acholi identity (the poetic introduction is written in a mix of Acholi and English). The unconventional use of the English language (e.g., the use of erasures), underscores the restlessness of the persona occasioned by the different issues they confront—disconnection, racism, loss, and longing. The effect of this is a chant-y and musical feel to the poems, a tribute to Bitek’s Acholi culture of orature. In the poem “Ash,” Bitek uses the white space to create a jolty feeling but she also leans into the poem’s theme of slavery and being cut off from her home of birth:

having been locked to land & free to home we discover ways to salt from ash

also salt licks also salt panning what did we need the sea for

never bound by the ocean until the slavers came down the Nile & marked us

us terrorized us enraged us subdued faces drawn yet still here still here still

i can draw you a map.

The sub-section “The Lock poems,” which, while formatted in a more regular fashion, use repetitions that make them feel like chants. Punctuations are not very important here, which creates a sense of urgency as seen in the poem, “Lock 7” (excerpt below):

after battle after battle after battle they return to the same spot same question

what is beauty

women with ravaged bodies yes blackened

unsmiling & gaunt beyond slender

this is what women look like after war

In A is for Acholi, Otoniya J. Okot Bitek is out to exert pressure on language and form, the same pressure(s) she inflicts on the issues she tackles in the book. She wants to set the terms and to truly belong in whichever corner of the world she places her feet. The reader? They are an active part of a deeply meditative journey with this collection.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions