You are asked to remove your shoes at the entrance. You thought it was insulting you were not given a heads-up beforehand. It was even more insulting that a ten-year-old boy barricaded the door before you walked in and said “Everyone, take your fucking shoes off.” What ten-year-old says “fucking”? His index finger quavered and hit your nipple as he mildly placed your name tag above your breast. You did not wear a bra. Your nipples peeked through your scrubs.

You did not wear socks either. You’re not sure what odour your feet are giving off. You’ve worn these crocs without socks from your first day as an intern. The ten-year-old boy looks at your toes when you pull your right foot out of your croc. His virtuous eyes then do a quick take up and down your body.

“Just sit wherever you see a free seat,” he says as he moves to the side and points inside the room. You hand him the brochure. His eyes meet yours for the first time. He kisses through his teeth as he skims the block letters and images that have been slapped on the rumpled brochure. “If you want to hand these out here just stand beside me. You can give these out as everyone gets in” he instructs.

“How about everyone else inside already?” I ask. “Can I distribute these inside as well?”

“That’s up to you. People will be busy watching the performance though,” he says without looking at you. “Just wear your sandal shit and stand by me.”

You had a lot of questions. You had not planned on being here. You had not planned on being objectified by a ten-year-old either. You should try your best today. You would smile. Laugh when needed. Speak when needed. You wondered whether you should call. Just to see how things were. It would show that you still cared. You could ask whether you can come in today. They would say no. You would ask if they needed an extra hand. They were short-staffed. They would say no. They would thank you for today and then ask whether you wanted to be assigned to another station tomorrow. You would say yes.

You slide your feet back into your crocs and move to the side. Your right hand firmly grips the brochures. The palm of your left hand gently massages your stomach. The line behind you was longer than you had expected. There are only men in the line. They have already taken off their sneakers. Each pair has been strategically placed on the floor to the left side of the line. They rest in a curious horizontal line. Some of the men make quick eye contact. Others scan their surroundings, and their eyes intentionally avoid meeting yours. The ones that stare adhere to the male rule of law and examine your body. Some of their eyes stop at your breasts where your nipples greet them.

You remember the morning of your first day.

“How does it feel to finally wear something that makes you look unfuckable?” Flo had asked. You remember laughing as your feet rested on the round rattan coffee table.

“Oh, I’m fuckable even in pink scrubs. I’ve heard some nuns get it in sometimes. That outfit’s much worse.” You drew a cross against your chest. That was a fun morning for you both. She made you sweet potatoes for breakfast, massaged your feet, made you coffee with only milk in it and you both danced to Freshly Ground’s “Doo Be Doo” before you frantically left the house for the clinic. You don’t remember the last time a morning felt that good. You’ve lost count of the days smiling felt effortless.

You force a smile as the men stroll past you and enter the room. Your left-hand tremors as it hangs in the air. You hold the brochure up so that the reading is clear. You watch as they all hastily analyze the brochure you have politely thrown in their face. You want to feel insulted when none of the men takes the brochure from your hand. You want to say something. Sell the brochure. Market the cause and urge them to be active members of society. You want to explain why you’re here. Convince them why they should care. You want to speak more; you want to feel again.

“You think I should go inside?” you ask the child. It’s just the two of you left standing outside.

“I mean if no one’s taken them from out here I don’t know how lucky you will be up in there.”

“There is a lot more people in there. I can talk to them before it starts,” you insist.

“It’s mad packed. Why are you giving these out here anyway and today of all days?” he asks.

“I’m going in.” You take off your crocs and stand in front of him.

He pulls up his pant legs then motions you into the room with his index finger. He’s arrogant. In that casual way that most men are. But he’s ten or nine or eight or eleven. He’s young. Too young to have let you know with his body that you might be assertive, but he still has a dick.

Inside, there is duct tape all over the windows. What you thought was sunlight shining through the windows are bald bulbs hanging from the ceiling. You count. There are about eight light bulbs. This much light is not good for anyone. You shift your eyes to the people in the room. There are only about fifteen of them. Ten were the men in the line. Only five men were inside the room before you arrived. They only occupy the chairs in the first two rows. The boy’s a liar, you think. Or he can say “fuck” but he cannot count.

You remember the faces of the anxious mothers on your first day as an intern. You remember being surprised that this many women could be in labor on the same day. You remember the pep talk from the head nurse. “Do whatever you can to keep them calm. Until that baby arrives it’s important that they know they are in safe hands. That’s your job.” You recall transcribing her instructions into your notebook. You recall your first delivery that day. The sheer joy you felt. It wasn’t about the over-exhausted mother who you forced to hold a slimy baby that she couldn’t yet decide whether she loved or hated. Or the family who threw their arms in the air, cried, and talked to the baby as if it knew who they were. It was not their day or the babies. It was yours. You were there. You helped take a human out of a uterus.

You told Flo after six months on the job that you would like to be a mother. She said babies poop in your womb. You were both lying on the floor of your living room that night chewing paper, rolling them into balls and throwing them up to the ceiling. They leached onto the coved ceiling. Flo said, who knew saliva was basically glue? That was a fun night for you both.

“Imagine taking a shit but it’s your shit and the baby’s shit. You’re basically shitting a multiplicity of shits. Anyway, I think we will be terrible mothers,” she had said.

“It will be attached to my placenta so I’ll carry that guilt. You have the luxury of deciding what kind of mother you will be. I don’t know if I have much of a choice if I am carrying it plus you did dream that you ate your baby once,” I said. We both laughed. “You’d be a terrible mother,” I said.

It had occurred to you a year ago that for you to exist, Flo had to be breathing. You knew that was unnecessary pressure to put on an individual. That loving someone that intensely was dangerous. Maybe even psychopathic. But no one ever teaches you how to love. No one ever teaches you how to be anything. You’re just told that there is a right way and a wrong way of being. Of loving. Of being a mother. Of being a good nurse. Of performing femininity. Of performing. That’s it. You think it’s just all a performance. But this. Flo. Loving Flo. That you learned on your own.

You walk towards the men. Your palms are sweaty. You have been standing for too long. It was advised that you stay off your feet as much as you can. You’re starting to feel thumping in your lower abdomen. It doesn’t feel like someone is stabbing you in the abdomen just yet, but you know that if you don’t leave here soon the murderer in your uterus will begin his assassination.

As you approach the chairs, your eyes read the words on a shirt of a man seated at the end of the second row. One of his locs covers the first letter of the word. It reads “rganizer.” You stand beside him and tap his shoulder.

“I’m trying to give these to everyone in here. Did you organize this? Can you help me give these out?” you ask.

Your hand massages your lower abdomen.

“How about a how are you first?” he says.

“Can you help me?” you ask.

Your hand massages your lower abdomen.

He pulls out his palm, and you place the brochures in his right hand. You notice the scars. You do not know whether they are scars or fresh bruises.

There was a time when you would have been concerned. You would not have hesitated to ask him what happened. You would have concerned yourself with his feelings. Listened to him rumble about how he bruised himself on a stove. Or he might have told you he intentionally harmed himself. You would have carried his pain. You would have told him to seek help or be more careful around the stove. You have told him about Flo. About her practice. About how she is the only practising therapist in town. About how she is all about healing. You would have given him her card. You would tell him Flo is a great person to talk to. You would tell him that she practices holistic healing. You would even offer to drive him over to Flo.

As a child, you were told that if you. A girl. Showed compassion to strangers. It was a sign. That you were inherently a good mother.

You continued to rub your hand over your lower abdomen as he read through the brochures. His index figure meekly browsed through each of the sentences. He nodded his head with approval. He was a lot more patient than the others.

Your slow rubs on your belly reminded you of Flo’s foot rubs. Your thoughts take you all the way back to the night of. When you complained about back pain. About the sharp pain in your abdomen. You thought it was kidney stones. You felt nauseous. Nina Simone’s “My Baby Just Cares for Me” playing at a low volume through the speakers as Flo smeared ointment on your back. The pain slowly subsided and you remember falling asleep, dreaming that you were sitting on a cloud drinking thick blood from a wine glass. You remember waking up abruptly like someone had deliberately pushed you out of your dream, you remember being drenched in sweat and Flo frantically turning on the lights. You remember leaping out of bed to use the bathroom and then seeing blood diffused across the beige coloured sheets. You remember that night at the clinic. You remember saying. “That could not have been a baby. There was so much blood. That could not have been my baby.” You asked Flo to pack up and leave your apartment a week after. You could not decide which loss was worse. Losing her or the baby. You read somewhere that you might be in a manic state after suffering a miscarriage. But no one ever teaches you how to grieve.

He interrupts your thoughts. “Is this not the place where women go to get abortions?” he asks pointing at the title which reads “Heart Matters needs your donation.”

“What?” you ask. This time you scan his face. He’s gap-toothed and when he smiles you notice the bull ring piercing nudged between his gums.

“I mean it’s a woman’s clinic, right?” he says. “I’ve heard it is famous for abortions and shit.”

“We are a women’s clinic. We specialize in women’s reproductive health. I work for the maternity ward. Can you help me give these out?” you say.

Your hand massages your lower abdomen.

“I don’t mean to offend. It’s just there’s a bunch of dudes in here and I might have to explain to them what this is all about. You know,” he says and flicks one of the brochures.

“We are asking people to volunteer. It is a blood donation fundraiser. Hospitals all over the country are doing this. There are people fighting for their lives who need your help. We are a women’s clinic” [You run through the script] “that focuses on reproductive health. The first and only one in the town. But we have a first aid section too that is open to everyone. You can come and stitch up,” you point at the bruise on his arm that is yellowish in color.

“Oh,” he looks at the bruise and laughs, “I’m a performance artist. I use my body to create my art so that means I may hurt myself sometimes. I’m Jimmy,” he pulls his hand towards yours motioning to shake his hand. You decline. “I think you know this is a gig for artists. Right?” he asks.

“We are spreading the word wherever we can,” you say. Your hand massages your abdomen.

“Look” he points to the front. Standing in front of the on-lookers in the front row is another man. “That’s my boy Nameless. He’s a performance artist too. Like me. He’s about to do his thing,” he says “I’ll give these out, but you just stay and watch. It won’t be long.”

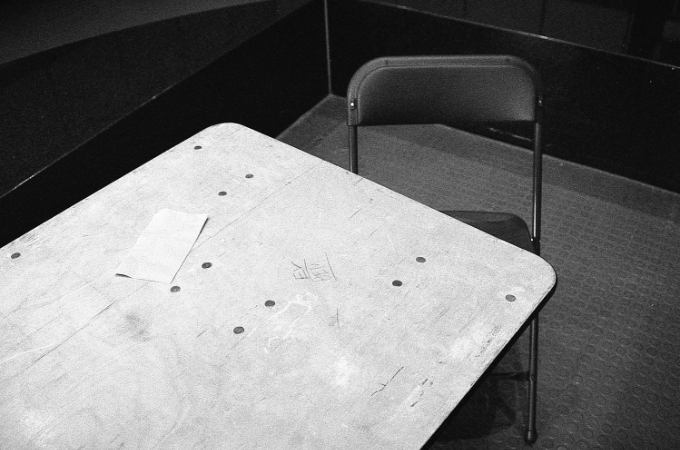

He jumps up and walks to the back of the room. The lights begin to go off one by one until there is only one bulb left, at the front. It lights the centre where Nameless sits on a chair. The rest of the room is so dark that you don’t know whether you’re still rubbing your lower abdomen or your thigh. You could not leave even if you wanted to.

“Lady and gentlemen,” Jimmy announces. Nameless still sits by himself in the front so you assume Jimmy is speaking from the back of the room. “We present Nameless!”

The chair he sits on is white and so is the table he rests his hands on. He doesn’t lift his head to look at the on-lookers. You watch as he pulls a knife from the left side of his blue denim jacket. He spreads his left hand on the table. Without giving the on-lookers a cue or an introduction to his performance, he begins to run the knife slowly in between his fingers. He starts slow, he is gentle. You watch the knife closely, still rubbing your lower abdomen.

Pa. Pa Pa Pa Pa Pa. Pa. Pa. Pa Pa. Pa. Pa.

He starts to increase the pace. He lifts his head and seems to be looking at the crowd as his right-hand weaves a knife between his fingers. You start at a sharp pain in your abdomen. You should leave. But you cannot see anything apart from Nameless. You have been forced to watch this. You could shut your eyes. You do not. You keep watching. You watch when the first contact happens. Blood splurges out. You cannot make out which finger it is. From the looks of it, all his fingers are bleeding because his movement has increased in intensity.

Pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa

You do not know when it happened but now, you’re squeezing your lower abdomen your nails are digging into your scrubs with pressing intensity that if you had claws for fingers, you would have dug into your stomach. You cannot decide which is worse, the throbbing in your lower stomach that feels like someone is deliberately squeezing your uterus or watching a man or yet a boy attempt to decapitate his own fingers. It starts to feel like whenever his knife and skin come into contact the worse your pain gets. You want to yell “STOP!” but you keep watching. You watch as the floor begins to swallow his blood until eventually, he slows down, the lights come on, and the on-lookers clap.

Pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa

“Yo,” someone taps your shoulder. It’s Jimmy. “You’re fucking bleeding,” he says.

Photo by Matthew Moloney on Unsplash

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions