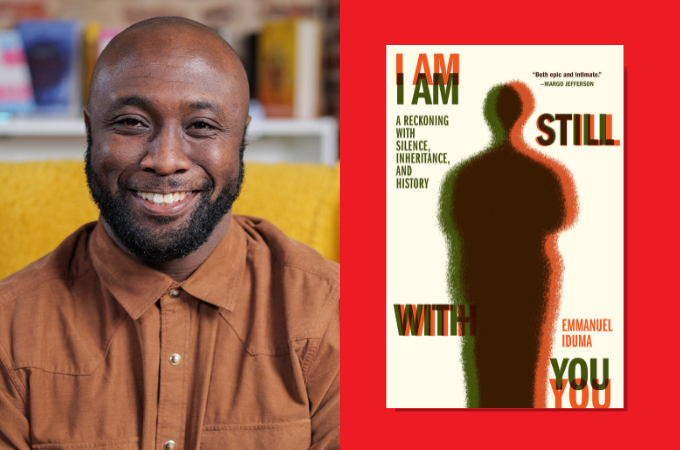

At the outset of his memoir, I Am Still With You writer Emmanuel Iduma reminds us that Olaudah Equiano is perhaps the best-known precolonial Igbo man. A formerly enslaved person from the Kingdom of Benin (now southern Nigeria), Equiano was shipped to the Caribbean, gained his freedom, became an abolitionist, and wrote an autobiography in Britain that was published in 1789. With that historical reminder of writing talent, political engagement, and forced transatlantic migration, we begin a whirlwind of travels in contemporary Nigeria by plane, okada (motorcycle), van, bus, keke (tricycle), and Uber. Iduma sets off in search of his paternal uncle who fought in the Biafran War of 1968-70 and never returned home.

Although born in the Igbo region of Nigeria, the writer begins his travels from New York – the city where he completed graduate work in art criticism and writing. His sense of self-doubt and unease upon arriving to Nigeria in 2019 after many years in the U.S. connected me to his journey. Similar to him, I felt like a tourist in Nigeria – a sentiment he continued to have until he encountered the familiar – his then fiancé, writer Ayobami Adebayo.

Confounding the search for traces of his uncle is the absence of government and historical records on events surrounding the Biafran War (also known as the Nigerian Civil War) and those who suffered casualties. Despite it causing 100,000 military casualties and killing up to two million people from starvation, the war was not taught in primary or secondary Nigerian schools during the author’s youth. The three oldest brothers of the author’s father fought in the war, but it is only the author’s namesake who never returned home.

As the writer Emmanuel journeys in pursuit of clues about his disappeared paternal uncle Emmanuel, his investigation becomes a search for the elders of his family. The writer’s mother died when he was four and his father, a Presbyterian pastor who also studied in the U.S., died 10 months prior to Iduma going back to Nigeria permanently. With his own father deceased, the writer must rely on the accounts of other elders in his family to learn details about his missing uncle.

An Igbo tradition of taking the first name of the father as a surname makes it difficult to trace families. This lack of specifics regarding family history is something I found interesting from my perspective as an African American because we are quite aware of how our family trees reach a dead end when we try to trace them beyond American shores, but it is eye-opening to see a continental African facing obstacles ascertaining familial details about grandparents and great-grandparents. Of course, it is not just Igbo tradition that makes it difficult to discover family lineage but the larger context of social upheaval – in Iduma’s case, civil war, and in my case, the Middle Passage and enslavement.

Emmanuel Iduma describes himself as a Nigerian and an Igbo. Yet he confesses to feeling estranged initially from the town of his family and its ethnicity. Because his father was a pastor who moved around Nigeria often, the writer wasn’t very familiar with Afikpo, the town in Igboland where his family is from. The author also confesses to not being able to complete a sentence in Igbo without using an English phrase. His linguistic limitations prove a barrier when he questions people about the hidden history of the war. They aren’t quick to trust him.

The Igbo are one of the three largest ethnic groups in Nigeria along with the Hausas and the Yorubas. In addition to these three large ethnic groups, Nigeria is comprised of more than 300 additional ethnicities speaking about 250 languages. What are some differences between the largest ethnic groups? The writer tells us that”“(unlike) the Yorubas…whose precolonial communities were monarchal…the Igbos have no king — …they were a collective of various autonomous communities.” The ruling class of the Hausa, on the other hand, allied themselves with the British colonizers, and the civil war was believed to have been fought between the Hausas and the Igbos.

A shocking one-third of Biafran families are believed to have lost a family member who never returned home following the war. Iduma reminds us that Biafran independence groups still exist in Igboland today and that the Nigerian Government has declared the Indigenous People of Biafra a terrorist group. He believes that the agitation for Biafra will continue as long as the war is not acknowledged and atoned for. Yet the writer is no ethnic separatist. As he emphasized, he is Nigerian and Igbo. And both he and his brother went against the tradition of marrying within their own ethnic group by marrying into Yoruba culture.

Given the dead end that Iduma reaches in trying to ask his family about the disappearance of his uncle, he is forced to rely on scant historical accounts. He researches books on the Nigerian Civil War which was declared by the government of Nigeria following Biafra’s declaration of independence. He also visits historical sites, such as bunkers and now-overgrown air strips, that were pivotal during the war. He receives referrals to elderly persons, and in those situations where he is able to establish trust, he questions them about the war with the hope that he can discover clues regarding his uncle.

As Dr. Chike, an acquaintance of Iduma in Lagos stated, people are the carriers of history when history is erased. Yet interviews present a challenge because family accounts of the war are repressed. Also, because Biafran independence is still seen as a threat to the Nigerian Government, people aren’t keen to speak on a topic that could put them in political danger. On one occasion, when Iduma is in Ahiara, the epicenter of the war, he is told he needs journalist documents to ask questions and get answers from the people he is conversing with.

It is in Ahiara that a public intellectual reveals to Iduma the shocking statistic that 70 percent of the guns in West Africa are in Nigeria. Another interesting war fact that was revealed surrounds August Martin – an African-American, Tuskegee Airman who was the pilot on a plane that crashed as it attempted to transport supplies from Equatorial Guinea to Biafra; the entire crew died, including Martin’s wife.

Regarding craft, in those instances where Iduma reaches investigative roadblocks regarding his uncle’s disappearance, his family history, and the Biafran War, he turns to speculation – a tool of fiction and nonfiction writers alike. He underscores his technique when he states, “It is of no use speculating what lives are possible for the dead…Yet it is similarly unnecessary to keep the living from their consolation, the living, who must keep speculating.”

In regards to structure, don’t expect a simplistic narrative arc. There is a linear narrative, but some events surrounding family, history, and politics weave in and out of the linear progression; they occur, disappear, and then resurface. Just like the Emmanuel personas in the memoir. The author admits, “What happens in my mind as I relate to my deceased uncle or mother or father is a feeling of being out of step with linear time, in which memories of the past have no sequence.”

I don’t believe that Emmanuel Iduma set out to be poetic in this book; his writing style is almost journalistic. But the body of his narrative captures the poetry of living and dying. Its language, with its ability to transport me through time and across space, beckoned me to travel.

My one regret is my sense of having lost new friends when Otibaba, the motorcycle guide in Ahiara, and Gift, the driver in Uli, were no longer in the narrative. Their knowledge of the landscape, along with that of many, many others, helped lay the foundation on which Iduma wove the essential threads connecting his stories.

***

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions