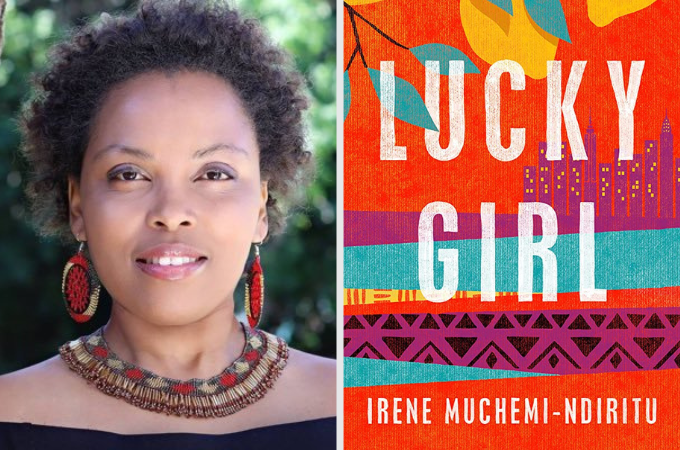

Two analogies became increasingly significant while I was reading the novel Lucky Girl by Kenyan writer Irene Muchemi-Ndiritu – a roller coaster and a knitted sweater. A rollercoaster because of the sense of expectation I felt in Chapter Nine when the author’s first-person narrator Soila leaves us suspended over a myriad of life’s possibilities. Soila says:

When the winter sun warmed my face I opened my eyes and it all came back. My bad fortune, my hell to pay for fornication – it was really true. It hadn’t been a dream. I was pregnant.

With this statement, writer Muchemi-Ndiritu tightens the chains of the narrative and leaves us perched at the top of a rollercoaster wondering how fast and how steep we will fall with this young woman who has kept us engaged with her life story.

In Chapter Nine, we’re already well-acquainted with Soila, the Kenyan narrator, who left Nairobi for New York to study at university. We’ve watched as she’s adjusted to life in the U.S. and tackled the challenges of studying abroad. We’ve observed as she’s entered into a healthy sexual relationship as a single woman, despite coming from a family with traditional views on marriage, and despite suffering the psychological consequences of sexual molestation by the family priest. And now she’s a pregnant college student.

More on the sweater analogy later.

In Lucky Girl, Soila relates her experiences growing up in a family structure and within a home, both of which are constructed like a cocoon of safety. Her overbearing, devoutly Catholic mom has created an almost impenetrable family shelter following the suicide of Soila’s dad. Residing in the home are Soila, an only child, her adult aunts, and Soila’s grandmother Kokoi. Soila’s mom rules over her homestead with almost tyrannical power and makes sure everyone follows her line of command.

Two things puncture the shelter of the cocoon – the first is Soila being sexually molested by Father Emmanuel, her mother’s priest. The second is a camera gifted to her at age 16 by her mother, which allows the narrator to visualize life beyond the confines her mother has built. Having harbored an interest in studying abroad, it is the sexual molestation by the family priest that forces the narrator to double down on her plan despite her mom’s naysaying. Ironically, Soila must get away from Father Emmanuel to experience her own resurrection. She asserts, “leaving my home felt like a rebirth.”

As she discovers a world beyond the limitations of her mom’s restrictions, the shadow of her aunt Tanei lingers in the background. Tanei is the most adventurous of the narrator’s aunts living in the mom’s abode. She is enrolled in nursing school in Nairobi, but she yearns to study fashion. When she tells her sister, the narrator’s mom, of her plans, her overbearing sister halts her in her aspirational tracks. Studying fashion isn’t going to happen under her roof. Hoping to forge her own life, Tanei moves out of her sister’s house and ends up living at the Y. She eventually becomes a mistress to a married man. And when there is a bombing at the US Embassy in Nairobi, Tanei is nearby and becomes a victim of the explosion.

A question hangs over the narrative. Could a similar unforeseen misfortune befall our narrator if she doesn’t follow the dictates of her mom?

Once Soila is accepted to study in the U.S., her life merges with that of 1990s New York City. She methodically contrasts the American city with Nairobi, Kenya as if the two locations are at war with each other in her consciousness. The New York experience dominates the novel, but Kenya remains a constant because the narrator goes home during school vacations, and her mom visits New York as well.

At the university in New York City, she befriends Leticia, an African American student of whom she states, “In a strange way, it felt like I had run into mother.” Leticia is a reflection of the positive and nurturing aspects of her mom. It is through her friendship with Leticia while being roommates for five years, both on campus and off, that Soila learns about race and power in the U.S. and gleans how to distinguish the subtleties of racism. Her upbringing in a privileged Nairobi family taught her about social class and how her Kikuyu ethnicity differed from that of other ethnic groups in Kenya. New York relays tragedies such as the Guinean/Liberian immigrant Amadou Diallo shot by New York police officers 19 times when he reached for his wallet. The city offers a close-up view of gentrification and how it affects racial minorities in the U.S. And as time progresses in the novel to the early 2000s, the tragedy of 9/11 looms large in the narrative as well.

Yet in typical American fashion, New York City also delivers on the positives. After the death of a close friend, Soila begins to question the worth of the business major she completed at her mother’s request – a field of study she felt didn’t prepare her to learn about the world around her. The city nurtures both her refound interest in photography and the love she feels for Akhenaten, an African American artist. It is her deep love for her boyfriend that makes the grind of New York City tolerable. Both Akhenaten and photography represent the circular moves writer Muchemi-Ndiritu makes in her narrative structure by returning her protagonist to interests she previously waylaid but then comes back to as a more mature person.

In addition to the contrasts between New York City and Nairobi, there is also the dichotomy between Grandmother Kokoi and Father Emmanuel. Soila describes her grandmother as her universe; whereas the abusive priest is someone she is constantly trying to avoid. She says in Chapter Fourteen that Kenyans have experienced “the colonization of property, body, and mind.” Perhaps no one symbolizes that colonization better than Father Emmanuel. Personally, as someone raised in the Catholic Church, I have come to view its history of colonial oppression and sexual transgression as appalling and dispiriting. So, when Grandmother Kokoi refers to Enkai, an androgynous God who lived in the mountains and was at one with animals and nature, my inclination is to follow the lead of the grandmother in regard to ethics.

And the sweater analogy?

Soila tells us towards the end of the novel, referring to her mom, “I looked at her like she was a sweater that had been knit inside out.” Indeed, the changes in the mom by the end of the novel are as disconcerting as clothing worn on the wrong side. Yet, as I reflected on the narrator’s sweater simile, I was made aware of how the author, Muchemi-Ndiritu, is a master of knitting together a narrative and then pulling away at the threads to unravel it. There is one point in the novel when the narrator states how she longs to be back home where culture, tradition, and religion matter, then she moves wholeheartedly in the opposite direction away from those goals.

Soila has to work hard to reach her goals and earn her luck in this novel. She has to reckon with life in societies labeled developed and developing, experience the colonial legacies of racism, question the value of education in late capitalism, and test the boundaries of romantic and familial love.

In her debut novel Lucky Girl, Irene Muchemi-Ndiritu shows us how her fictional character Soila risks it all in order to retain the good experiences while tugging away at the threads of the bad. Her ability to learn from life’s ordeals on two continents, shed encumbrances, and pack up the positives to carry with her into the future exemplifies the luck she finally forms on her own terms.

***

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions