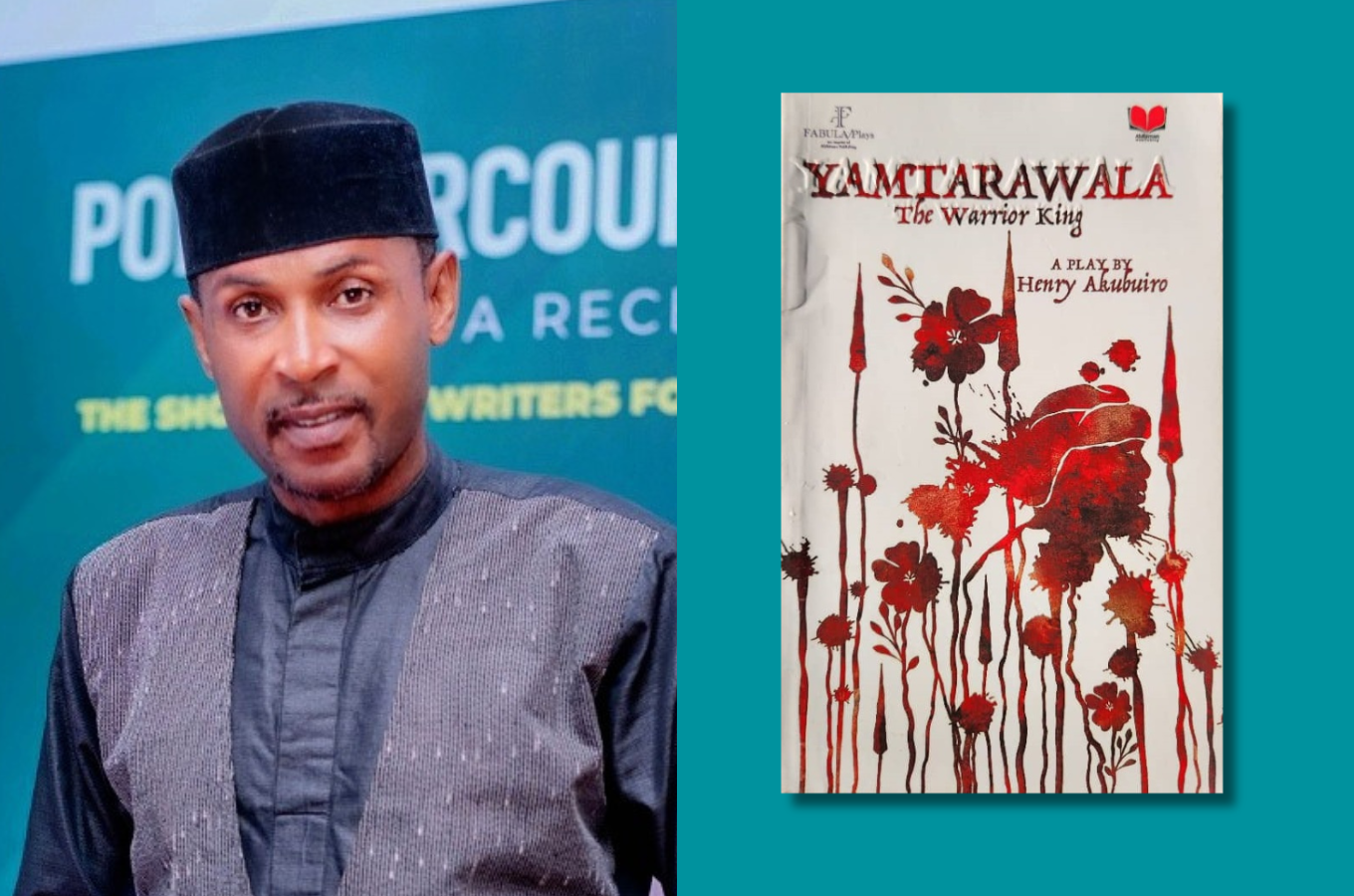

Yamtarawala, The Warrior King by Henry Akubuiro is shortlisted for the 2023 Nigeria Prize for Literature.

***

Yamtarawala, The Warrior King opens with a poignant flashback backpedalling 23 years before when we encounter Asga, the soon-to-be Queen of Ngazargamu, who has just lost her husband to Egyptian invaders. The story then pans to the present. The king of Ngazargamu is dead and the kingmakers decide to whom the kingship would fall on.

Abdullahi, the first son, is rumoured by the guards to be a bastard, and the second, Umar, is considered the rightful son of the dead former king. A marabout is summoned, and the two sons of the king are put to a test. The marabout decides that Umar be king. Umar is crowned immediately, and Abdullahi, disappointed and bitter, flees the kingdom with loyalists and stolen arms. Abdullahi vows to return as a “chief” and ruler to possibly avenge his loss.

Henry Akubuiro plays with drama that struggles with itself to be originally dramatic. It’s hard to place this book where it could perfectly fit. It defies labeling and straddles between fable and tragedy, but it doesn’t quite hit any mark in the end. Yamtarawala brings up the issue of sibling rivalry and the efforts of the protagonist, Abdullahi, later known as Yamtarawala, to become king of Ngazargamu. Yamtarawala details how a man, burdened with the wrongness of the verdict of the kingmakers, sets out to make things right and take back what belongs to him.

Set in the 16th century, the rest of the play details Abdullahi’s sojourn across kingdoms and chiefdoms as he tries to conquer lands and territories using his wit and masculine charms that come off as cheeky and condescending but effective in the end. The story takes a long dive here. Abdullahi whose name changes, abruptly, to Yamtarawala, and often to simply Yamta, goes into a conquering spree. At the end of his sojourn which spans many years, he settles in the kingdom of Biu, and establishes a new dynasty. He grows paranoid eventually, believing he would be betrayed by his children. He conspires and attempts to assassinate his son, Marivirahyel, whom he considers a threat. When he finds out the plan fails, he sinks into the ground and is later revealed dead.

Close to the end of his life, Abdullahi notes how his self-given “prophecy” had come to pass. He is now chief and ruler. And it’s easy to feel pity for Abdullahi if only there were strong reasons to feel compassion for him. The play takes away the empathy that could have served the protagonist well. There were only left missed opportunities to have made Abdullahi a perfect tragic hero, or a perfect main character in the least. In the end, there’s little to connect with in the story. There’s no reference back to Ngazargamu, nor of his brother Umar. Their stories end where they begin.

Akubuiro’s rendering of the play comes off as fabulistic but lacking the customary absurdity of fables. It also tries its best to sell itself as a work of tragedy but doesn’t promote its titular protagonist as a strong enough tragic hero. Yamtarawala could be a Jay Gatsby, King Lear, Macbeth, Michael Corleone, or an Oedipus, but he doesn’t fit into the archetype required to be one. The playwright paints him only under the light of a crazy, misguided opportunist who uses his wit and charm to entice powerful women.

The worst form of art is that which deconstructs itself. The foremost rule of comedy is to never explain your own jokes, to never make the audience look unintelligent. The best dramatists are those who gave the audience or readers interpretive free will. Perhaps, the main weakness of Yamtarawala is its decision to explain every detail, taking away from the readers their right to make out the story by themselves. The use of the narrator in the play created a large gulf that restricted me from unraveling the story myself. Like Abdullahi, the play pits itself against itself so much so that rather than come down, at the end, to a satisfactory denouement, the narrative arc encounters a cul de sac.

A number of fine points in the work can be alluded to fate. Akubuiro saunters around the idea of providence and uses it well. There are considerable details to unfurl in Abdullahi. For one, his motivations are clear, however misguided and selfish. Was Abdullahi meant to be king of Ngazargamu, or was he fated to lose the throne? Was his child fated to betray him and bring him to ruin? Was his tragic end predetermined? Akubuiro leaves so many questions open on the table. But many aren’t so rhetorical, and answers could have been provided. The most important question, perhaps, is the true parentage of Abdullahi. Was he truly a bastard son?

Yamtarawala isn’t a great play, but it is a good one with lots of promise if properly stage-directed. The characters weren’t strong enough to leap up from the book at me. They were merely characters who revolved around an arc that never quite reached a satisfactory end.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions