At first, I want to fight the feeling, but then it becomes oddly comforting. It’s new to me, everything is new to me after the funeral, and so is my disgust when I see him for the first time in months that morning in June.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen him like this. He is frowning but his eyes are watery. One leg is stretched out into the aisle between the tables, as if he’s preparing himself to bolt at the first opportunity. I can tell he doesn’t know how to respond to my indifference. I can tell this experience is completely new to him, not getting his way.

The longer it lasts, the more I relish it. There’s something satisfying about watching his face, normally so self-assured, twisted into something so pained. He looks like he hasn’t slept in days and hasn’t been eating well. The fine lines that are rarely visible on his skin are highlighted on his forehead, like someone’s fingernails have left their mark. He looks like I feel, except for the feeling of dark gratification swimming happily in my stomach.

“What’s going on with you, Garth? You’re not returning my calls,” he says, his voice rising with a ping. After so much time away from home, I love the way that sound falls on my ear.

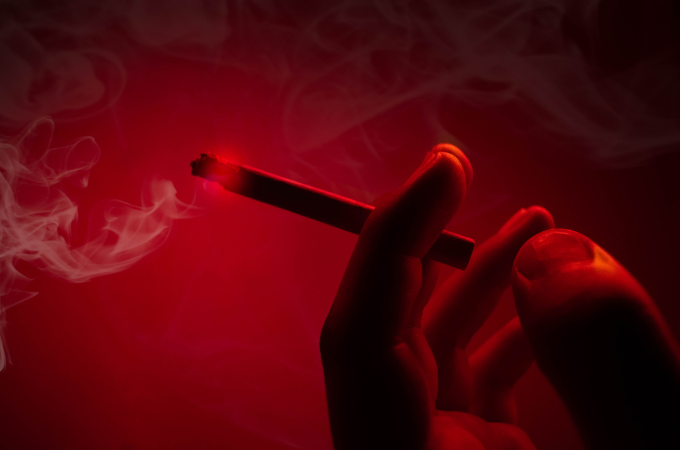

We’ve been sitting in this cubicle for close to fifteen minutes without saying a word. The first thing I did after sitting down was light a cigarette. After three puffs, I placed it in the ashtray and now it’s sending an acrid curl of smoke into the air between us. It’s 10am on a Monday morning, so the restaurant is practically empty. We’re the only people in the smoking section, except for a waitress who keeps barging in to check on us.

It’s our first time meeting here. He prefers places like Pigalle. The Spur at my local mall is far beneath him. This meeting must have been very important for him to drive all the way from town to Kuils River, dressed in his standard dark suit and tie. I picked the location because for once I have the upper hand.

“You know why I’ve been quiet, Marcus,” I said and smiled inwardly at the cool monotone of my voice.

“I understand that he was your uncle, but it’s been more than two months. At some point, you have to return to the outside world.”

“I will. Just give me time.”

“I hope so,” he sighs. The light from the ceiling-high windows alongside our table dances on his skin and hair as he shakes his head. I can tell by the narrowing of his eyes that he’s carefully assessing my request for patience. As an auditor, he thinks he can read people as well as he reads his balance sheets.

He can do so much better than me. We both know that. Even though he’s become a bit rounder in middle age, he still has the tall, solid frame of his rugby-playing days. The pasta and red wine belly that droops over his belt has made him even more charming. And, in his well-tailored suits and Italian shoes, he cuts a dignified figure. Unlike me, he has the kind of features that white people find pleasant. His skin is brown but not too dark, a deep sun-burnt tan, his nose and lips are full but not overly big, and his hair snakes around his head in lush waves when it’s long, and even at a modest length, it falls on his head in a delicate baby-doll pattern that almost makes him seem sweet. But you have to get close to him to notice the fine swirls.

As for me, my friend Fatima once told me I should have studied literature at UCT. The lecturers would’ve loved me, she said, because I have “a certain look.” I know what she means. I see my grandmother’s round nose and full lips each time I look in the mirror, even though my mother insists I look like my father’s people, who are all green-eyed and Kagga Kamma yellow. My hair is a messy afro that I barely maintain. Now and again, whenever I can afford it, I go to the hairdresser to make sure that it gets a good wash and conditioner. It’s not just white people who don’t associate my look with intelligence. When I first went to an English-medium school in Elsies at the age of eight, the first time my mother sent me outside my community for my education, the teachers all spoke to me in Afrikaans. I suppose they didn’t expect a little Bushman to know the queen’s language.

I know what Marcus really values about me is what he considers my status; the fact that my name had appeared in the paper once upon a time and that he could boast to his buddies that his friend the journalist was attending such and such an event with this or that minister or could get him the contacts for some or other person in a position of authority. Also, I’m a safe bet. Looking at us, people would never guess the nature of our relationship. Besides, people like him have always owned people like me.

“I just don’t get it,” he continues in a whisper, as if he is talking to himself. “Until now, I’ve never even heard of this uncle of yours.” All these years, I thought, as the smug sensation in my belly made itself at home. All these years, and Marcus still acts like we are having some kind of star-crossed love affair that gives him the right to access my most private thoughts. Memories that I have tucked away so securely, even from myself, that they sometimes catch me off-guard when they surface in a quiet moment late at night before I go to sleep.

It would never occur to him that the reason he doesn’t know about my uncle was deliberate on my part. He still thinks he’s the first man I ever fucked. Little does he know the depths of my secret. It started long before we met, at the age of thirteen. The upstanding citizen that he is, he expects everyone to take him into their confidence. He doesn’t know what it felt like looking down at my uncle’s lifeless face in his coffin, knowing that it might be the first time in almost seventy years he’s known peace. He doesn’t know what it’s like to be at a funeral and feel like you’re standing at a mass grave of all your family’s tragedies. He doesn’t even know that I lost my job at the bank a year ago.

There’s one thing I’ve always liked about him, though. It’s not his money or the nice things he lavishes on me – the designer clothes and the weekend getaways in Franschhoek, Bettys Bay and other dorpies where no one knows us. It’s not even his good looks. Unlike the other men, I let him kiss me. Not because I like him. But because it shuts him up. It maintains the illusion that our coupling is more than sex. Men like him need that. It fools them into thinking that they’re not just filthy animals driven by un-Biblical lust.

With the others, I make it clear: nothing above the waist, and they like it that way. Most of them are young, so they’re perfectly okay with nothing more than a quick release before they have to rush to class or the gym. There’s only three that I see regularly. We joke about my obsession. I even give them a score out of ten. I rate them according to taste and stamina. By now they know what I enjoy and what they need to do to keep me happy and to keep them coming back. I like to smell before I taste. I like their distinct motions and sounds as they slide in and out of my mouth. The steady rocking. The gasping for air. The thump-thump-thump. Nathan is old books. Shane is whiskey. Justin is cinnamon that fills the back of my throat. Heavier, sweeter, bitter, depending on the season and time of day.

I don’t go to all that trouble with the rest. They’re just one-offs I connect with on Grindr. I miss them. I haven’t seen any of them since he died, and I would rather have met with one of them than this fool. I only agreed to meet him so he’d stop harassing me. He doesn’t know about the others, and I feel no guilt about it. After all, he’s the one who’s married with God knows how many children.

Until now, we’ve been meeting at least once a month, except for the year I lived in Abidjan. I don’t do it for the thrill of a clandestine affair. I swear, I don’t. But I must admit Marcus is good to have around. For all his flaws, he has some uses. Not only for sex, but in general. Many a time I’ve called him in an emergency to bail me out. When I’ve run out of money or when I need a lift somewhere, which is often because I don’t drive. He thrives on being Mr. Reliable.

“No, thank you,” he tells the waitress without looking at her when she comes to our table for the third time. “We’re going soon.” His eyes stay on me, fierce like a Hindu mask. I focus on the ripples of light bouncing off his hair and skin, rather than look him in the eye. My uncle’s death gave me an even better excuse to keep him at a distance. We’ve been doing this since high school. And sometimes after our love-making sessions, if you can call them that, I find myself wishing my mother had never sent me to a nice school more than thirty kilometres from home where boys like him are rife.

God, I resent the way he curls up behind me after sex. But then I feel the impressive firmness between his thighs. Generous as any of his expensive gifts. Pressed into my back, still pulsing with the aftermath of our passion, and I remember why I keep indulging him.

Photo by Aman Upadhyay on Unsplash

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions