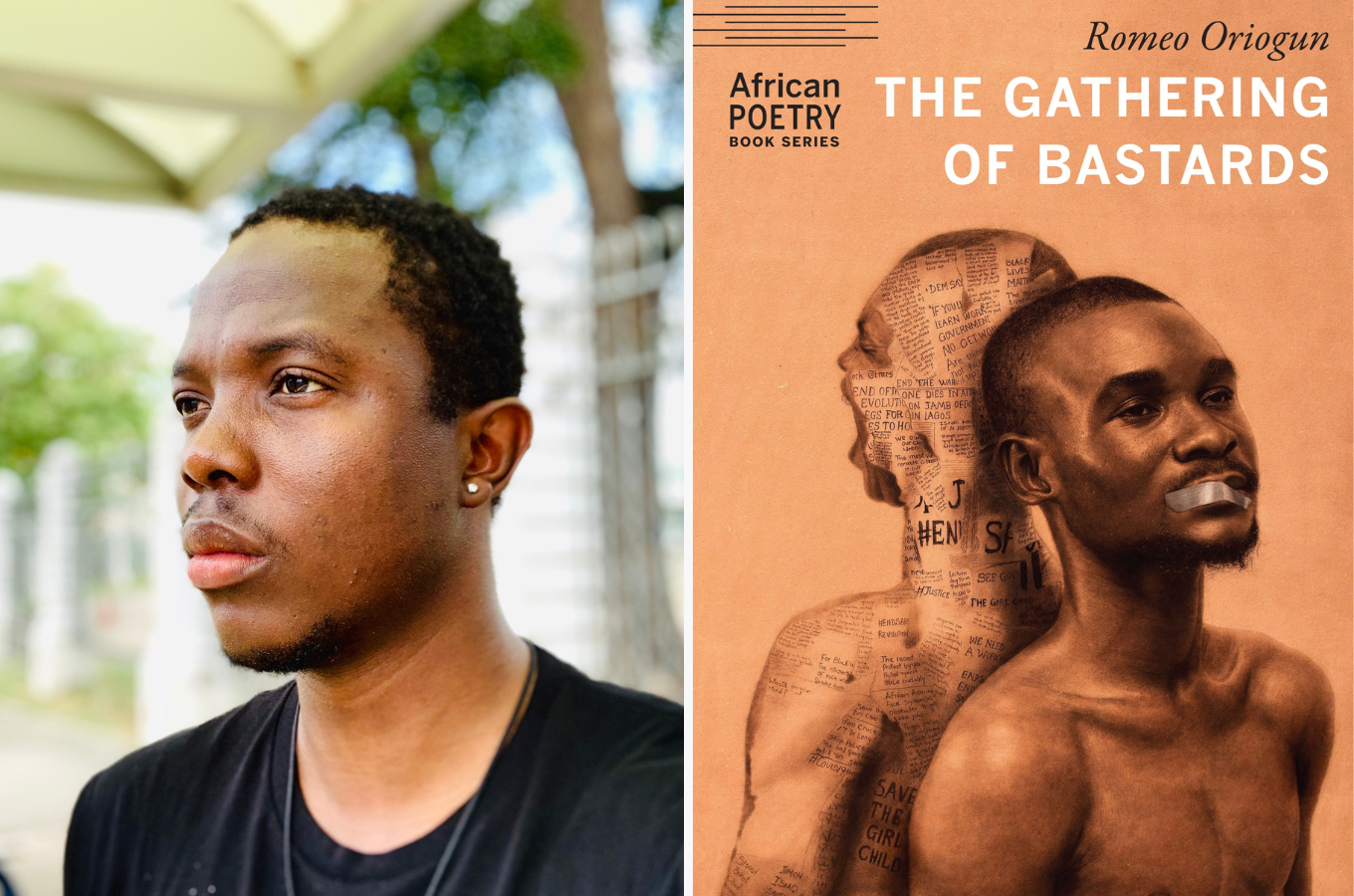

In his most recent collection of poetry, Romeo Oriogun is at prayer. The Gathering of Bastards (University of Nebraska Press, 2023) is a prayer, not against exile per se, but against exiling, that tendency of the home or the country to eject. Clustered around themes of departure, remembrance and wandering, this collection of 71 poems tells the story of migration across the borders of time, place and even the body.

There is water dripping off almost every poem, because the water “will always lead us home”. Water is no stranger in Oriogun’s poetry in general as it has featured prominently in previous collections. However, in The Gathering, water takes center-stage, and the poems are like ripples inscribed on water – “…now I write in water,/ I know there is no translation for our sorrow”.

Throughout the collection the lament of exile rings out. Like the voice in Ramah which cannot be silenced until a reconciliation becomes possible. The to and fro of water is the background melody for the gathering of the bastards. The bastards of this collection are not without fathers; they are, rather, without country.

The Bible had asked, “can a mother forget the baby at her breast and have no compassion on the child she has borne?” (Isaiah 49:15-17). In the context of the mother being the motherland, the answer is an unfortunate yes. Whereas The Gathering is a prayer that exiling may not occur, for those already cast out, it becomes a prayer for a reconciliation, that exile may end.

The collection begins with a fisherman praying unsuccessfully not to find floating bodies in the water. By the final poem, the speaker is “yearning for freedom/ like a bird rattling against the cage/ of his life, singing nothing, demanding/ neither grain nor water/ just the open air, the skies, then death”. The bird asking to be set free is a pregnant metaphor because “all departures are birds/ flinging their bodies against the cage of exile”. In seeking for the open sky, the bird has no illusions of immortality, it knows it would die, it just does not want to die in a cage, or in exile.

The observation that the caged bird demand neither grain nor water is important. Because “the hunger/wracking a migrants body/ is movement”. Exile is altogether a different kind of migration. It is a precarity, and “For those who have journeyed across the sea/ love is not enough to declare home, and you … are awake at night, counting the many ways/ a country can desert a man”. Elsewhere, the poet recalls “I left the country and the country left me and that even my body is empty of a country”.

Those who leave everything behind and try to sail into exile may be rescued from the sea, they may receive solidarity and love, but they still may not find home. This is because being plucked out the water is not the same as “arrival”. To be “empty of a country” is a painful position to be in. Philosopher Hannah Arendt argued that statelessness was the first stage to the Holocaust. The “right to have rights” is always rooted in belonging to a country.

There are a few more words to say about the concept of being “empty of a country”. It is not enough that one has left the shores, there is this painful sense of dis-place-ment, or “being without place” throughout the collection. Emptied of country and wandering the earth, the speaker realises that, “I have no language for belonging”. Even at night, the exiled is awake, counting not sheep, but the “many ways/ a country can desert a man”. This desertion is potently expressed in the loss of language – not that the exiled has lost their language, but the language of the homeland no longer has purchase in exile. Of shurroty, we are told it is the “act of begging/ for food in an Italian city, the disappointment of exile”.

Even those who have money have found themselves stranded, unable to communicate the needs of the body when they cross the boundaries of language. Like, asking for your meal “spicy” in Lagos does not mean the same thing in Stockhom. But what do you do when you have no money and no language? Through the memory of a dead migrant, we meet other migrants begging, shouting shurroty and “not knowing its meaning/ other than I am starving outside of language”. The loss of language compounds the precarity of the loss of country.

As if recounting what has happened to some authority, in the poem “The Sea Dreams of Us”, the speaker laments that “I have given up country/ to be here, by the seaside, where what looms over me/ is uncertain”. The arrangement of the lines gives a special flavour to uncertainty, it is not that the exiled is not certain, he is rather fully aware that uncertainty follows when one is emptied of country. The uncertainty of exile does not end with an arrival, alas, “there is no end in exile, there is only the road echoing/ in blood”. Because exile is both personal and societal, the speaker declares that “our bodies are countries/ outside of borders and silence is also exile”.

Despite the pain of this dislocation, the poet does not see exile as death. A “re-homing” may be possible. But even for those who manage to find a new home, there is still the guilt – of not drowning at sea; of finding home while comrades continue searching for a home; and of the knowledge that they may never find home. The poem, “A Phone Call from Exile” recounts such survivor’s guilt when a veteran migrant calls one who has found a home in America. But instead of celebrating this safety, the speaker laments that “my guilt is America”. When the co-traveller calls again, “I, who am ashamed of my comfort/ do not answer”. Perhaps there is nothing left to be said. The survivor must plod through his guilt while the other continues the search for home.

Though the one who has found a place to exile in is not in position to home the other migrants. The least he could do is to write, urgently. Therefore, “I, a man without home must begin to write… lighting the world ahead of refugees travelling to the shadow/ of a new country”. Again, we are reminded that arrival doesn’t make it a home, and refugees are always going to be in the shadows. But the telling of these tales gives voice to the trauma that modern migration has become. It is almost as if destiny chose the speaker to survive so that the various stories may not perish like the co-travellers.

You would think the exiles are happy to finally be rid of the old country. Far from it, they carry with them memories and emotions that never go away. Like the song recalling the Rivers of Babylon, Oriogun reminds us of “how alive/ is my country in songs, in exile”. There is a reason Nigerian music is selling out arenas in the West – the inexplicable warmth of a country experienced from afar.

Even though the speaker is aware that “what evil has befallen/ me has befallen those ahead of me throwing them out/ of their countries”, his fervent prayer is “let me touch/ my forehead on the doorpost of my home”. There is a yearning that music and other pieces of home one finds abroad cannot satiate. Like the caged bird in the collection, grain and water could wait, what comes first is freedom. So when the misfortune of exile strikes, the yearning is not for food, music, or any other comfort. The yearning of the exiled is to one day return, and to touch his forehead to the doorpost of home. Can he?

***

Buy The Gathering of Bastards by Romeo Oriogun: Amazon

Avimulta April 19, 2024 00:50

"The “right to have rights” is always rooted in belonging to a country." What about when one has been robbed of their rights. Sidelined ,forgotten and homeless in one's own country.