“For once I myself saw with my own eyes the Sibyl at Cumae hanging in a cage, and when the boys said to her “Sibyl, what do you want?” she replied, “I want to die”

– Petronius

I.

Take a seat and tell yourself a story.

Do you remember the first time it happened? That day, you woke up in a house that wasn’t your father’s and mother’s, two months into a new job in another city and away from the people you call home. COVID was slipping off like the end of a heavy harmattan season — dissipating but heavily present. Nose masks were still fashion items, only, six people in a room of ten would have them on. But this is not about COVID. It is about an illness you do not call an illness. Back to that morning.

You are of the opinion that memory fails everyone in different measures. With every recollection, details chip off like clay off a potter’s wheel. But this is not about pottery. It’s about the molding of a strange other. That day was like every other. You’re at least sure about this.

Like I said, you woke up. But you never walked. You laid in bed and stared at the POP ceiling. It wasn’t paralysis. You did not walk because you were afraid to die. You were sure that if you moved an inch from the slim mattress on the top bunk, you would take your life. So, you laid there. Staring. Waiting. You cried. And then you did not cry. Nothing could make you feel, so you got tired of trying to feel.

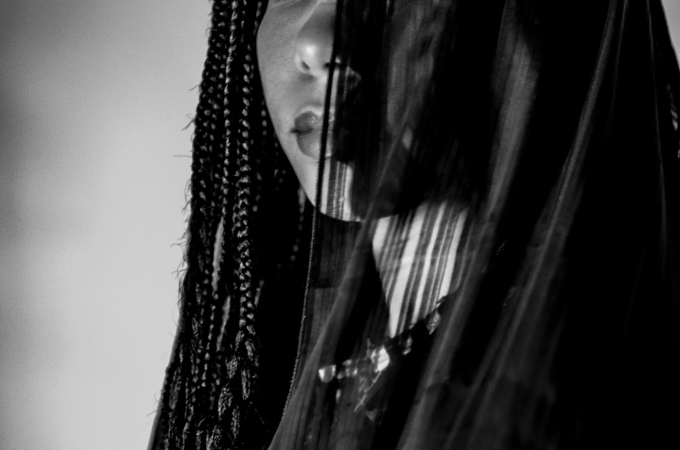

It had begun with the touch of a familiar friend: the thought of your worthlessness. And then, it became a consuming cloak. Like foot testing water temperature before immersion.

This was the beginning of something you had always known. You’d had flashes of this gloom as a child. But this time, it stepped out in full and mockingly asked, “may I?” – knowing you had no power over it. You watched as it diffused into your soul and became one with you. You, a helpless spectator in the room of your life.

Here’s what you find: when darkness becomes a close friend, it starts to feel like light. This new space you’re plunged into is the only place you know what to do with your life: lie still while missiles of self harm torment your mind.

The day ripples. People talk to you. You hear, but you cannot answer. There are no words. You mechanically do your remote job from a place of eerie stillness. Every puncture on the keyboard a quiet reminder of your worthlessness. Your foreboding death as a nobody. “You’ll die by your own hands,” Your mind chants with a maddening, chilling certainty. You think, “I don’t want to die…” You wonder, “Do I want to live?”

II.

Uncloaking

The next day. You get up.

Everything feels normal. You think, “I’m not going to die,” like lagging response on a call with bad reception. Only, your response is 24 hours late. Life feels normal. You laugh with everyone. All is well again.

Then you call your man who is not your man, who you want as your man, even though you know he doesn’t want to be your man. You tell him what happened. Sketchily. In a way that doesn’t make it sound too serious, lest he thinks you’re crazy and leaves you. Even though he’s not with you. “You should have called me,” he says in concern. “Did you call N? You should have called N,” he adds. N is a mutual friend.

But how do you call to say you’re afraid to stand up because you’re afraid to die? How do you tell someone else that the cloak of death doesn’t stop on the back, shoulders and arms like a jacket? Instead, it covers from head to feet. Think of a balaclava and a burka. The opening in the eyes is to stare at the ceiling, paralysed with fear and numbness. Until the garment is soaked with the sweat of your trepidation, as dark hands take them off to dry. You think you’re free, but the cloak is drying. Waiting to be reworn on your self.

III.

Re-cloaking

When it happens again, it’s in your parents’ house. At this point, you know that something is wrong with you. This is not normal. The four walls of this house are supposed to have no space for darkness. How did it slip in? From where? A while ago, you said goodbye to your sisters while they left for church. Everything was normal until something suddenly switched off and you started crying. You cry heavily. Heaving. Sighing. The sounds you make remind you of the warning Nigerians sometimes give when in ire, “if I catch you ehn, you will cry blood.” It feels like you are crying thick, fresh, blood.

The reminder this time is a heavy hand. Like a scolding parent, your worthlessness chides you. It questions why you think you should even be alive. You fucking worthless fool. So, you do what you do when you’re chided harshly: you cry. “Why? Why am I even here? I hate being here because I’m so useless. Why was I even born?”

At these moments, nothing exists anymore. Nothing but the steady, eerie chant, “you will die by your own hands.” You don’t even remember that you’re surrounded by so much love from people who worry for you. Root for you. Call you. Pray for you. From people who see you for you. And love you.

Your favourite things: the smell of clean clothes, the laughter of happy people, the taste of good food, the quiet beauty of art galleries…

…tiny things that bring you great joy: singing songs you love, crocheting as it rains, reading, making friends, the smell of the earth after rain… Everything becomes a distant blur. Nothing but nothingness exists. The cloak obliterates memories of great joys: your parents, siblings, your friends, cake slices…

You forget everything. And you just slip in like someone dying in their sleep.

But it is not you. It is the darkness. You don’t know when or how it happens. Your self just slips in mindlessly as feet into a pair of clean, warm socks on a cold day. Death feels so close. It’s on your skin. You’re deeply afraid of what you can do to yourself. And then, this fear propels you. The fear pushes you off this bed.

You run. Grab your phone like a life jacket and you call N. You tell her to meet you in church. It is urgent. You are crying. Your hands are shaking terribly. You know if you don’t leave this house, you will die by your own hands. So, you have to run.

She worries about you, and tells you to hold on tight. Hastily you wear what you can and run away. Seeking asylum in the country of a person. Because people are countries. They have maps and boundaries; they have other people with different degrees of distance in their own geographical space. But this is not about countries. It’s about a strange visit to a strange place.

You and your friend see each other in church because it is like the middle ground between both your houses. It’s closer for both of you. She holds your hand, and pets your head like a child. You hate it. But you love it. Because it anchors you to earth. It tells you, “hold on tight for me. For us, the community of people who love you.” You try. You cry terribly while at it. Then you do not cry. You’re dry and exhausted. You feel like the word “carcass.”

IV.

RESHAPING

You say, “My favourite title of a book is Binyavanga Wainaina’s One Day, I Will Write About This Place. I love the title. I love it because it sounds like the assuredness of finding the words to talk about something. Sometimes to find the word to describe a hazy, paralysing, and heavy emptiness that tries to swallow you whole is hard. Something you cannot put a face on. How do you say, “I’m afraid to stand up because I’m afraid to die?”

How do you tell someone else that the cloak of death doesn’t stop covering till it consumes whole? People will say you are mad. Boys will say you’re looking for pity love. But, one day, I will write about this darkness. One day, I will talk about this temporary death. I will expose its secrets. And it will be defeated. Until then, my head shall be above water. I will fight. Or so I hope.”

Take the seat away. You are done here.

Photo by Michael Starkie on Unsplash

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions