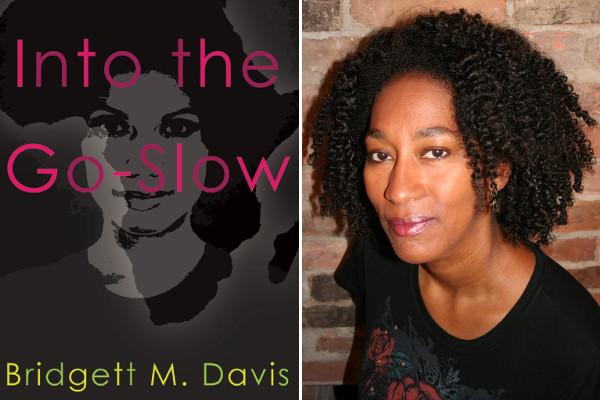

Pub. Date: September 9, 2014. The Feminist Press at CUNY. 320 pp. Buy HERE.

***

Stories about African Americans going off to Africa in search of things past and lost have become familiar. But in Into the Go-slow (2014), American novelist, Bridgett Davis, breathes a new life into this classic motif.

Into the Go-Slow revolves around Angie and Ella, two sisters born and raised in Detroit. When we meet Angie, she has recently graduated from college and about to set out for Nigeria on an unusual quest—for a dead sister.

The official story says Ella, who had been living and working in Lagos as a journalist, was run over while crossing a Lagos motorway. But in a city as elusive as Lagos, there are always many sides to a story.

Angie, herself, cannot suppress the nagging feeling that her sister’s passing was not simply a hit-and-run affair. She believes that retracing Ella’s steps, reliving her life in Lagos, essentially, chasing Ella’s ghost through the devious streets of Lagos will reveal the truth about how Ella died.

That’s why, for me, Into the Go-Slow is an urban adventure story.

The novel takes the reader through a dizzying array of events—both misfortunes and triumphs— that take place in Detroit, Lagos, and Kano. The part of Angie’s story set in Lagos is a series of intriguing encounters with the chaotic welter of Africa’s most loved and most frustrating city.

Davis has a thing for space and setting. She is able to capture the spirit of a place with a poetic flair that I found to be a joy to read. When Angie swivels through the city of Kano in a Vespa while holding tightly to the male rider, she sees the city in its enchanted materiality. The old city of Kano built in the 15th century reveals itself through a veneer of the magical that Angie describes as “a sepia-toned photograph overlaid with jewel tones.” Angie and her companion meander through the “sinewy…arteries” of the market place and its “tributaries of slim alleyways.” As they speed away, we are told that the “shimmering” Jakara River “ran alongside, chasing them.”

Into the Go-slow is also a story about the lives of women. Apart from the fact that most of its principle characters are women, Davis’ novel celebrates women as political visionaries, as mothers, as lovers.

She explores the limits of the feminine body, but also its uncommon capacity for healing. In Ella, we see the figure of a broken female body pushed to its limits but never beyond redemption.

And even after she dies, Ella’s body survives in the form of a ghostly remain that then initiates for Angie a mournful but beautiful journey of self-discovery

Davis’s novel is as much an African story as it is an American story.

As a Nigerian, Davis spoke to me. She took me back to what I like to think of as the weird ’90s. It was the decade of botched democracies, sky-high inflation, psychopathic rulers, and widespread panic.

Davis captures a good bit of what was so unsettling about the political climate, but she also captures the lighter mood of the decade—the obsession with Michael Jackson, American ballads, and what would end up being the last years of Fela’s life.

In Davis’ work, Africa is not this abstract idea. Her Lagos, her Kano bristles with abundant life, around which she weaves a lovely story about those small but lasting redemptions that only a sister’s love can bring.

Manny April 10, 2015 16:05

I read the book and really liked it. There was something really adventurous about it although I felt like slapping Angie a couple of times. But it surprisingly left me with this feeling of nostalgia for the Nigeria of the 90s ... certainly not the best of times but very adventurous times for all, even then secondary school students like I was.