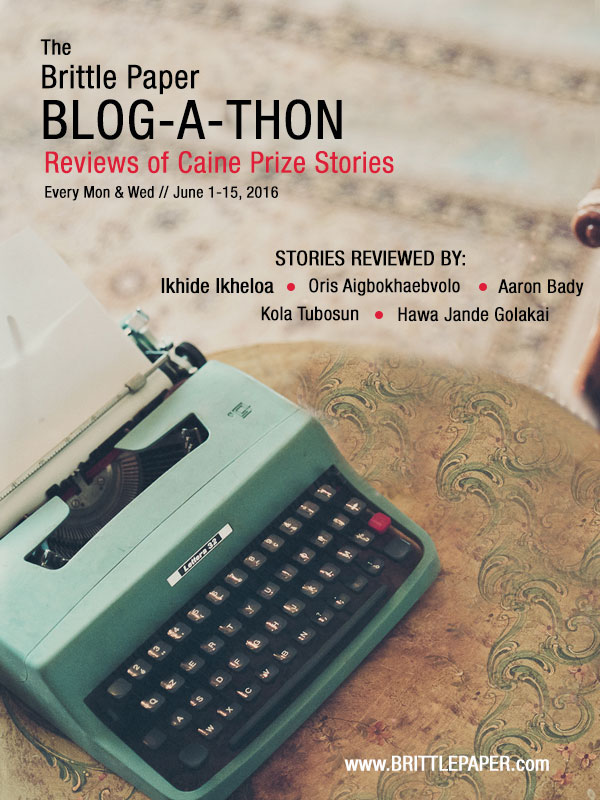

Hey Brittlers! Welcome to our 2016 Caine Prize Blog-a-thon. In the next two weeks, we will post reviews of the five stories shortlisted for the 17th edition of the Caine Prize for African Writing.

In just about a month, one of the five lucky shortlistees will take home the £10,000 prize. In the meantime, can we all talk about the shortlisted stories? We want to know what stories you liked or hated and why. We’d also love to know what you think these stories tell us about African literature more generally.

To get the conversation off to a productive start, we have assembled a team of five literary critics in the African literary community and asked them to jot down a few remarks about the stories.

Here to kick things off in grand style is the beloved Ikhide Ikheloa.

Scroll down to read his review of Lidudumalingani’s story. Enjoy and be sure to leave a comment!

The 2016 Caine Prize shortlist is out, and it features five interesting stories from writers equally as interesting and eclectic. One of the writers is the South African, Lidudumalingani, a lovely mind born in the Transkei who seems to spend his days roaming the catacombs of South Africa, armed with nothing but his eyes and words, brilliant witness to what the streets see and do not see.

Google him. You will like his portraits. You will like his stories. Google him.

Who is Lidudumalingani? There is a great piece on Brittle Paper here on him and his great skills as a street photographer. He maintains a lively presence at the literary website Africa is a country. Enjoy him riffing on Fela, making you wish you were prancing around on the soccer fields of your childhood. But read this piece, The Art of Suspense, about that wondrous era of the radio when you listened to and imagined soccer through a radio. All his senses, literary and photogenic, come together before your eyes.

With “Memories We Lost” Lidudumalingani is now smack in the klieg lights of literary history. Read this fascinating story about love and life in the gripping shadow of mental illness and marvel about how a writer can weave pretty and gripping portraits with powerful words. Lidudumalingani is a sensitive soul. His ability to conjure powerful images with just the written word is phenomenal, awe-inspiring even.

“Memories We Lost” is more than a story about mental illness. It is about love between siblings who dote upon each other—and love for the land that houses and nurtures their heart. It is about community. More importantly, it is an unapologetic and respectful portrayal of life in Lidudumalingani’s corner of Africa without a recourse to the pity party of poverty porn. When Lidudumalingani writes about mental illness, the description is so vivid. It is as if you were right there, as he describes this illness that the nameless protagonist calls “this thing.”

“Memories We Lost” is an affecting piece. The reader’s heart warms to the nameless sister as Lidudumalingani expertly sketches the blurred boundary between lunacy and creativity, the creative bleeding into the dark valley of lunacy: “She and I spent that week doing sketches. With a pencil she could sketch me onto the paper such that it appeared as if I was alive on the page, another me, more happy, less torn, existing elsewhere.”

Harrowing is the mindless violence of mental illness, but even more harrowing—and violent—is the community’s “cure” for the illness:

… the next day my sister would be taken to Nkunzi to be baked. This is what they did with people who heard voices or demons, as they called them; they baked them until the demons left them. What was even more terrible than the baking was that people had come to be convinced of it.

I had heard of how Nkunzi baked people. He would make a fire from cow dung and wood, and once the fire burned red he would tie the demon-possessed person onto a section of zinc roofing then place it on the fire. He claimed to be baking the demons and that the person would recover from the burns a week later. I had not heard of anyone who had died but I had not heard of anyone who had lived either. I could not allow this to happen to my sister.

As you read “Memories We Lost,” you are taken by the simplicity, grace and power of Lidudumalingani’s prose. The sentences touch you in the heart shyly; aroused, the soul stirs—and smiles at distant memories. Lidudumalingani loves the land and the villages of South Africa come into sharp focus as you read. He knows the land of his ancestors, intimately:

I stared out into the landscape that began in my mother’s garden and stretched far beyond sight. The sun was setting behind the forest and dust was floating everywhere. Where the dust was dense, one could see it sway this way and that way as if in the middle of a dance. A sophisticated dance, the kind that, I imagined, happened in other worlds, very far from the village. The village was settling into repose. The cold summer air had begun to torment the villager’s bare legs and arms. Everything was in silhouette, including the horses that trotted across the veld, the cattle that lowered their heads to graze, and the water that flowed down the cliff. The mountains, ancient but nevertheless still standing, were casting giant shadows over the landscape. The shadows stretched so far from the mountain that they began to exist as if they were solid entities on their own.

These are my favorite lines:

Those without torches or candles walked on even though the next step in such darkness was possibly a plunge down a cliff. This was unlikely, it should be said, as most of them were born in the village, grew up there, got married there, had used that very same field as their toilet for all their lives, and had had in overlapping periods only left the village when they went to work for the white man in large cities. They had a blueprint of the village in their minds; its walking paths, its indentations, its rivers, its mountains, its holes where ghosts lived were imprinted in their blood.

I liked “Memories We Lost.” It is a good thing that the Caine Prize is for African writing, not literature, because, as with most of the entries on the shortlist, there is no serious attempt to provide the structures that are standard for fiction—things like plot, setting, character, conflict, etc., indeed sometimes, it comes across as mere reportage with hints of creative nonfiction.

However, what this piece lacks in orthodoxy and structure, it more than makes up for with innovative approaches to keeping the reader engaged. As Lidudumalingani plots the twists and turns of the story through the eruptions of this “thing” that torments the protagonist’s sister—and the clan—you learn about the sangoma (google it). The reader is saddened by the fate of those in African communities who suffer from mental illness—how they are caught in violent superstitious and an abusive void and subject to despair and crushing loss. This story chronicles the reality: in many African communities, there are no facilities for the mentally ill. What serves as cures is oftentimes cruel beyond the telling of it.

From my perspective, there is a quiet battle raging between Diaspora writers and writers in Africa. The Caine Prize seems to be a proxy for that tension. Of the five shortlisted writers, three live abroad. I respect and admire the works of both sides, and I thank the Caine Prize [for African Writing] for promoting the writing from both sides.

I was taken, however, by the freshness and sincerity of Lidudumalingani’s “Memories We Lost.” The writing hearkens to a time of innocence, of the works of writers like Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Lenrie Peters, Camara Laye who sought to explain their rich and complex world with the English Language.

I will have a few things to say later about the 2016 Caine Prize shortlist (identity, purpose, etc.) on my blog (here), but for now, I salute the Caine Prize for exposing me to Lidudumalingani’s beautiful world. Who knew!

Read Lidudumalingani’s “Memories We Lost” here. We are eager to know what you think of the story. Do you think Lidudumalingani stands a chance of winning the 2016 Caine Prize for African Writing?

********

About the Author:

Ikhide R. Ikheloa is a blogger, social and literary critic who writes non-stop on various online media. He has been published in several books, journals and online magazines. He was a columnist with Next Newspapers and The Daily Times of Nigeria, where he held forth and offered unsolicited opinions on any and everything to do with literature and the world. And he currently blogs about politics and literature at https://xokigbo.wordpress.com.

Ikhide R. Ikheloa is a blogger, social and literary critic who writes non-stop on various online media. He has been published in several books, journals and online magazines. He was a columnist with Next Newspapers and The Daily Times of Nigeria, where he held forth and offered unsolicited opinions on any and everything to do with literature and the world. And he currently blogs about politics and literature at https://xokigbo.wordpress.com.

Bookforum talks with Lidudumalingani | Khanya Mtshali October 25, 2016 18:16

[…] like an extended monologue, with its lyricism and use of verse. The Nigerian critic Ikhide Ikheloa commented that some of the stories from the 2016 Caine Prize finalists read like “reportage with hints of […]