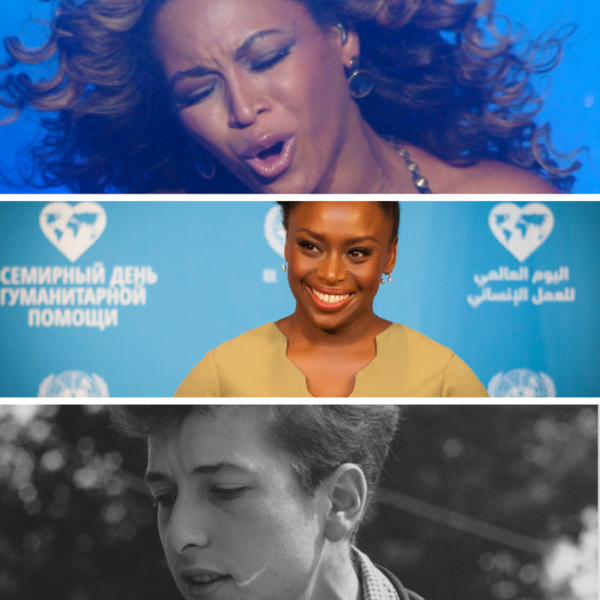

IN A RECENT INTERVIEW with the Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant, ahead of the Dutch translation of her We Should All Be Feminists chapbook, Chimamanda Adichie disclosed, in news that is now viral, that she would never perform expectations of gratefulness to Beyonce for sampling her work.

Roughly a week after this news surfaced, on 13 October, the day the death of Italian playwright and 1997 Nobel laureate in literature, Dario Fo, was announced, the Swedish Academy, in another connection between literature and music, decided that the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature would go to 75-year-old American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.”

This is urgent, so let’s get straight to the point.

First Premise

If you’re not a prominent, evidently-liberal writer like Salman Rushdie who has called it “a great choice;” if you’re a bit baffled like Jodi Picoult who has tweeted “#ButDoesThisMeanICanWinAGrammy;” if you’re untroubled like John Scalzi who has tweeted that “songwriting is writing, and Bob Dylan is one of the most influential writers in the last 100 years. It’s a defensible Nobel pick;” if you’re as infuriated as Irvine Welsh who has described it as “an ill conceived nostalgia award wrenched from the rancid prostates of senile gibbering hippies;” if you’re suspicious of the New York Times’ description of his win as “redefining boundaries of literature,” an interpretation the Swedish Academy ironically rejects; if you’re a post-‘70s generation writer or an aspiring one; then it is fair to conclude that you might find the choice of Bob Dylan wildly interesting or wildly questionable or outrightly ridiculous or Plain Sad. And you’ve probably asked, or are asking, or will ask Google why. The present writer, though, finds all of the above opinions to be legit.

Second Premise

Because, by virtue of winning it, Bob Dylan—famous American, famous singer, famous songwriter, and now the “greatest living poet,” according to the singer Mick Hucknall—thoroughly deserves his award; because Dylan’s contribution to literature has been deemed to be of equal worthiness to those of fellow Americans and all-time writing greats: Toni Morrison and Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner; because, in 2016, Dylan’s literary merits now make him, in the words of Alfred Nobel, “the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction” much more than those of the perennial favorites: Kenya’s Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Japan’s Haruki Murakami and Syria’s Adonis and Czech Republic’s Milan Kundera and fellow Americans Philip Roth and Joyce Carol Oates; because none of us can honestly claim to not have ever listened to American music all of which has been impacted by Dylan; because of all these, I have a few proposals for continued cordial relations between writers and musicians.

- That if Abubakar Adam Ibrahim had any regard for “new poetic expressions within the great Nigerian song tradition,” he should dedicate his NLNG Prize to Fela Kuti, or better still, give it to the worthiest candidate alive: Asa. Since the Swedish Academy has definitively argued that writers—these artists whose talent and hard work rarely bring them the audience they deserve—don’t always need prize monies, or at least not as much as their already-bankable musician cousins, Ibrahim should honorably hand over that award and its $100,000 money to Asa. Everybody knows that, being a writer, he doesn’t need it; and to make amends for the mistake of giving it to him, the 2017 prize must go to Olamide and Phyno “for popularizing poetic expression in indigenous languages.”

- That if MTV Africa Music Awards (MAMAs) had any respect for artistry that breaks grounds across genres of expression, they should have nominated Fiston Mwanza Mujila, 2015 Etisalat Prize-winning author of Tram 83, for also creating “new poetic expressions” by writing a novel structured like Jazz music. He, and not Sauti Sol or Yemi Alade or Diamond Platnumz, deserves to be named Artiste of the Year.

- That if the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction appreciated “new poetic expressions within the great Female song tradition,” next year’s prize should be jointly awarded to Adele “for distilling heartbreak in lyrical musicality,” Sia Furler “for penning such poetic hits as ‘Diamonds’ and ‘Titanium,'” Lady Gaga “for being the only pop queen who randomly mentions reading in her songs as if books actually matter,” and crucially, to one of the subjects of this essay: Beyonce, “for shining her saving lemonade light on feminist and African literature, for changing the life of an Orange Prize winner as well as that of Brunel Poetry Award winner, Somalia’s Warsan Shire.” Do they not see how she descended to Africa and first chose a novelist and then a poet just because she loves and supports what we’re doing? Don’t they see how giving her this would sway her to choose a playwright for her next album?

- That the Booker Prize judges should do the right thing in 2017 and give it to a rapper with the loudest “poetic expression:” Eminem. No, Kendrick Lamar. Or Nicki Minaj. No, Eminem.

Third Premise

Now that the leading literary institution of our time, the hallowed Swedish Academy, has confirmed that literature is of secondary relevance in a world blessed with music, now that it may have implied that, wherever they intersect, music legitimizes literature simply because it has wider outreach, Adichie’s comments become clearer, starker, truer: real artistry is in danger of being sacrificed on the altar of cheap popular culture demands. Adichie—arguably one of the five most talked-about, most-covered, most-impactful writers in the world in the last two years (Don’t ask me who the other four are; just trust that Elena Ferrante is in there)—is right in refusing to dance and offer prayers to Beyonce—the pre-eminent musician and cultural conversation-starter of our time—and it is appalling how we keep acting as though without Queen Bey’s Endorsement, her epoch-making body of work would remain unknown, unread, unappreciated, unwritten about. To this wild imagination, sane Nigerians say, “Nawa o.”

The most saddening aspect is that this obnoxious notion is sustained in willful ignorance about how association with Adichie has bolstered Beyonce’s brand and solidified her feminist credentials. In the past few days, I have thought often about commenters who do not know that, without Adichie’s lines in “Flawless,” there are actually culturally-aware human beings who might never have taken Beyonce seriously both as a feminist and as a megastar who tries to prove she isn’t merely another ubiquitous-but-replaceable product of pop culture, who succeeds in proving this by becoming a vehicle for Something. And so because of Adichie, they now accept Beyonce as an anchor of feminism—and if this reeks of elitism, it is only because every field has its gatekeepers. In March of 2013 when the song that eventually became “Flawless” surfaced online—then titled “Bow Down/I Been On”—Beyonce was criticized for chanting the seemingly un-feminist “Bow down, bitches, bow-bow-bow down bitches!” And then in December, “Flawless” dropped, with Adichie’s words putting Beyonce’s in context, and there was understanding. Los Angeles Times’ Carolyn Kellogg called the feature “astonishing,” and The Guardian’s Rebecca Nicholson wrote that it “carries power.” Still, Foreign Policy’s Catherine A. Traywick described Adichie’s words as “watered down” by Beyonce’s “banal brand of beginner feminism.” Which didn’t matter much because Beyonce was now feminist.

The “explanation-defying” Beyonce of 2016’s Lemonade exists so convincingly because she stands on the shoulders of the groundbreaking Beyonce of 2013’s Beyonce who herself leaned partly on The Feminist Gospel of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. It must be noted that had Beyonce sampled a writer or speaker of a lesser stature, the feature would not have drawn as much attention. Beyonce’s feminism got attention because it was aligned to Adichie’s—Adichie who by 2013 had two viral TED talks that fired her into post-literary celebrity, who was A-List enough to deliver the 2012 Commonwealth Lecture, who had ten years of a bestselling literary career in her purse. (Trivia: Bey’s solo career was solidified in the same year as Chimi’s: 2003 when both “Crazy in Love” and Purple Hibiscus dropped).

With her extensive adaptation of Warsan Shire’s poetry in Lemonade, Ainehi Edoro’s expertly argued piece in The Guardian UK (“Beyonce Is Not Shining a Light on African Literature—It’s the Other Way Round”) highlights how Beyonce taps into the literary traditions of Africa to shape her work’s sensibility. How she “looks to Shire’s oeuvre to—literally—find the language to express her own reality,” an artistic dependence that the media, in this fit of sustained hyper-excitement, simplistically depicts as “artistic generosity.” If Beyonce introduced Adichie to a wider audience who might never have known her work, if Beyonce ensured that she was the first African writer to have a Grammy nomination and chart on the Billboard Hot 100; if Adichie legitimized Beyonce’s feminist legacy among people who might never have accepted her stance, if Adichie ensured that Beyonce is now being talked about in classrooms in ways she never was; why then should one be expected to be thankful to the other when both have gained? Why then do we still insist that books and reading and intellectualism do not matter as much as music? Her Feminism Is Not My Feminism is not the contention here; the contention is what prompted that truth in the first place: expectations of gratitude. Because she owes nobody anything, there is no need to emphasize that she has admitted in the past that “I have had young people in Nigeria who probably would never have heard my TED Talk without Beyonce and who are now talking about feminism.” Because it is worrying that underlying this expectation is the assumption that literature is necessarily elitist and music is naturally populist and so, wherever these two cousins meet, literature must defer to music because nobody knows writers and everybody knows musicians and therefore literature is somehow a lesser genre.

This ridiculous attempt to get literary prowess to “bow down” to musical prowess colors Bob Dylan’s Nobel win. If he deserves the Nobel Prize in Literature for doing in music something that conventionally belongs in the realm of literature, then Teju Cole deserves a Grammy for rendering the rhythms of classical music in Open City and J. M. Coetzee deserves an Oscar for his fluid opera depiction of Lord Byron’s life in Disgrace. Through the language of his songwriting, Dylan undeniably revolutionized expressions of art and history, but the truth is that while language is the indispensable tool of literature, language is simply not the exclusive preserve of literature. Literary professionals, songwriters, scriptwriters, speakers: a host of professions primarily use written language. Dylan may have “created new poetic expressions within” language but not within literature.

Still, Dylan’s retouching of language rightly means a lot to the Circa ‘60s Generation and is of indispensable importance to pop culture, but then his status is not the contention here. The contention is whether a multi-millionaire music icon really needed to be awarded the media coverage and 8 million kronor ($932,786) traditionally meant for lesser-remunerated artists in the literary field. Whether literature needed to lose in its own backyard in order for music to gain. Soon, we might be told to be grateful that Dylan was chosen, that one of the greatest musicians in history has crossed paths with literature, in the same way that Adichie is told to be grateful that Beyonce had chosen her, had used her work to further the Queen Bey Brand. If this expectation isn’t imperialism-in-artistry, I don’t know what else to call it.

Like Beyonce’s sampling of Adichie’s work, Bob Dylan’s win will draw the attention of music lovers to literature, more people than usual will become interested in the Nobel prize for literature, and like Adichie’s upholding of Beyonce’s often-challenged relevance in the feminist movement, his win will become the most controversial in this century so far, but will also be accepted because it is an ordination by a literary force. And this isn’t the first time a literary institution has recognized Dylan: in 2008, he won a special Pulitzer Prize citation for “his profound impact on popular music and American culture, marked by lyrical compositions of extraordinary poetic power.” Sara Danius, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy and Professor of Literature in Stockholm University, draws parallels between him and the Greek poets Homer and Sappho, terming him “a great poet in the English-speaking tradition.”

Dylan’s prominence on betting sites was supposed to be a joke (New Republic even ran an article, “Who Will Win the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature? Not Bob Dylan, That’s for Sure”), but however the Swedish Academy winded up with him—to attract popular and long interest? Appease Americans by ending their 23-year snub? As a nod to a generation’s nostalgia?—it does not change the fact that the man is “not in the established canon of literary writers” as CNN puts it, that he is a globally famous singer-songwriter whose place in history had long been assured with his storied impact on art and politics and his ten Grammys, and perhaps crucially, that he is an artist who just doesn’t need the money. Bob Dylan doesn’t need the Nobel’s $932,786 and coverage, but Ngugi and Murakami and Roth and Joyce Carol Oates and any writer of literary fiction need that money and coverage. Perhaps not personally, but the promotion of their works need that money. (And the question of Need isn’t meant to be ethical here, must never be perceived as prescriptive because it simply is An Observation That Must Be Made). Instead, as The Atlantic tries to explain, “Dylan is winning 8 million kronor ($932,786) for his words as they are written and not sung—affording him a wild degree of praise for something that is not the main achievement of his career.” Is this the aim of the Nobel? To give the foremost award for primary literary achievement to a wildly-famous outsider-artist for one of his secondary achievements? The Atlantic goes on to deal a death blow: “Today’s award says that a byproduct of Dylan’s main job is as good or better than the life’s work of Murakami, Roth, Adonis, Ngugi.” Novelist Gary Shteyngart captures something as sad as it is humorous when he jokes: “I totally get the Nobel committee, reading books is hard.”

And so Dylan, literature’s torchbearer in music, emerges.

No matter how vehement the conversation becomes in coming days, this is the simple truth: the Nobel Prize in Literature is the Swedish Academy’s to give, theirs to brand how they deem fit, and so life, the writing life of loneliness and sweat and hardwork that doesn’t always pay off, would be easier if we simply congratulated Mr Dylan and listened to his Danius-recommended 1966 album Blonde on Blonde, and accepted the fact that some professions—music, acting, sports—will always be deemed more relevant than the rest. Let’s just hope that with Danius’ reiteration of Dylan’s status as “a wonderful sampler, a very original sampler,” Beyonce doesn’t win it in 2020 “for sampling Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Warsan Shire and bringing global attention to feminism and African literature through her unprecedented musical and cultural influence.”

Sane Nigerians say, “Nawa o.”

****************

Post image is an adaptation of images by Claudio Marioto and Archives Foundation via Flickr

About the author:

Otosirieze Obi-Young’s Transition story, “A Tenderer Blessing”, was nominated for a Pushcart Prize last year. His work has also appeared in The Threepenny Review, Interdisciplinary Academic Essays and Brittle Paper. He edited Enter Naija: The Book of Places, an e-anthology about places in Nigeria created to mark the country’s 56th Independence anniversary.

Otosirieze Obi-Young’s Transition story, “A Tenderer Blessing”, was nominated for a Pushcart Prize last year. His work has also appeared in The Threepenny Review, Interdisciplinary Academic Essays and Brittle Paper. He edited Enter Naija: The Book of Places, an e-anthology about places in Nigeria created to mark the country’s 56th Independence anniversary.

Fall Break Links! | Gerry Canavan October 22, 2016 09:01

[…] Coming. Teaching the controversy: Kurt Vonnegut in 1991: “Bob Dylan Is the Worst Poet Alive.” Imperialism-in-Artistry: Bob Dylan’s Nobel Win Is Proof Adichie Is Right about Beyonce. Local Boy Makes Good. But not too good: The Nobel Prize Committee Have Given Up on Trying to Get in […]