Many things rattled Achebe about Heart of Darkness. In his 1977 essay titled, “An Image of Africa,” he seemed astonished that Conrad could reduce Africa to mere prop or stage effects for the tragic story of one European life. For this, Achebe called Conrad a “bloody racist” and 10 years later—when the essay was reissued as part of a collection—a “thorough-going racist.”

This sound bite has gotten so much play that students of African novels have stopped reading the essay for anything else. They have become quite content to see in the essay Achebe’s criticism of Conrad’s racist assumptions and nothing more. But this, typically, is the fate of all things classic. The more we read them, the less we know them.

A while back, I was doing one of my many re-readings of Achebe’s essay, and this quote gave me pause:

“The eagle-eyed English critic, F. R. Leavis, drew attention nearly thirty years ago to Conrad’s “adjectival insistence upon inexpressible and incomprehensible mystery.” That insistence must not be dismissed lightly, as many Conrad critics have tended to do, as a mere stylistic flaw. For it raises serious questions of artistic good faith.When a writer, while pretending to record scenes, incidents and their impact, is in reality engaged in inducing hypnotic stupor in his readers through a bombardment of emotive words and other forms of trickery much more has to be at stake than stylistic felicity.”

Let me begin by pointing out quickly that hypnosis is a much misunderstood psychological state. A hypnotized person is not a zombie. Hypnosis has more to do with attentiveness. The hypnotist induces in the subject a strangely intense concentration on a single thought or train of thought. Hypnosis is a kind of captivation—something holds our attention or interest so totally that it blocks off not only distractions but also all peripheral vision. In a sense, hypnosis is a way of thinking.

In the quote you just read, Achebe is not too happy with novelists who do this to their readers. Like Conrad, they concoct a set of adjectives and imagery that they use to manipulate all that is seen, heard, and felt by the reader. They essentially hold their reader’s imagination hostage. Achebe describes what Conrad does as “a steady, ponderous, fake-ritualistic repetition of two sentences, one about silence and the other about frenzy.”

You may think Achebe is being a tad petty for complaining about Conrad’s adjectives. But that is not at all the case. As an astute novelist, he understands that for someone like Conrad, all the magic is in his style. In this same essay where he calls Conrad a bloody racists, Achebe is gracious enough to concede that “Conrad is undoubtedly one of the great stylists of modern fiction and a good storyteller into the bargain.” Conrad was that sort of writer who could do wonders with everything from adjectives to exclamation marks. Critics have said that there is something photographic about Heart of Darkness. Odd but Conrad writes like he is a film-maker working with light, sounds, and angles of vision to create moods and feels that tell the reader what and how to think about the world being presented before his or her very eyes. (Example)

How can such ridiculously beautiful writing conjure up for the reader the figure of Africa as a mute, mad, and incomprehensible thing? This is precisely what is, in a sense, monstrous about Conrad’s novel and what Achebe finds unsettling about it. But I also see in Achebe’s remarks a larger point about the art and wiles of novelizing. I’m not so keen on the distinction that Achebe makes here between writers with “artistic good faith” and those without it. I think that there is something necessarily “dishonest” about the work of any good novelist. Only bad novelists can be 100 percent honest.

Great novels are great for different reasons but one thing they all have in common is their tendency to jealously hold our interest or attention in ways that make us susceptible to the author’s suggestions about culture, politics, sexuality, race, gender, the beautiful, the ugly, and so on. It is in this sense that even a hardcore realist like Achebe still has to resort to some level of “hypnotizing.” What Achebe points out about Heart of Darkness but what I see as a problem with the genre in general is the simple fact that there is a Conrad in every novelist. To put it differently, there is nothing innocent about novels, especially the ones we have all learned to love so much.

Then again, nothing wrong with this hypnotizing business of the novelist. Really. After all, a hypnotist is much more than just a mere “conjurer of cheap tricks.”

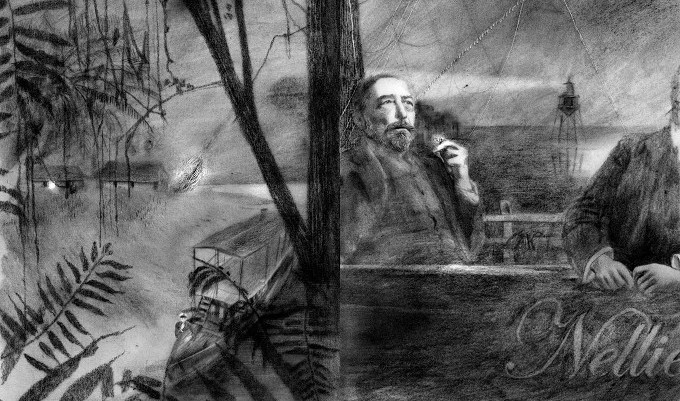

Feature and post images are from the graphic novel adaptation of Heart of Darkness made by Swedish/Kenyan artist, Catherine Anyango.

Here’s a slide show of images from the graphic novel. Pretty cool stuff. HERE

Full text of Achebe’s essay, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” HERE

Never read Heart of Darkness? Free e-copy HERE

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions