If you’re from Nigeria or Hongkong, you probably know Frederick Lugard as the elder colonial statesman, who invented indirect rule. But long before he became those things, he was a poor and lovelorn ex-soldier wandering through Africa looking for the big break.

Love and Empire.

A broken heart drove Frederick Lugard into the British colonial service in Africa. He was 29 and on military service in India when he fell madly in love with some woman. Lugard, they say, was a man “with immensely strong capacity for love,” so when the woman dumped him, he came close to losing it. “The shock…nearly destroyed his mind,” writes a biographer. So in 1888, “in a state of near insanity he went off with 50 sovereigns on his belt to seek adventure, and if possible, death” in Africa.

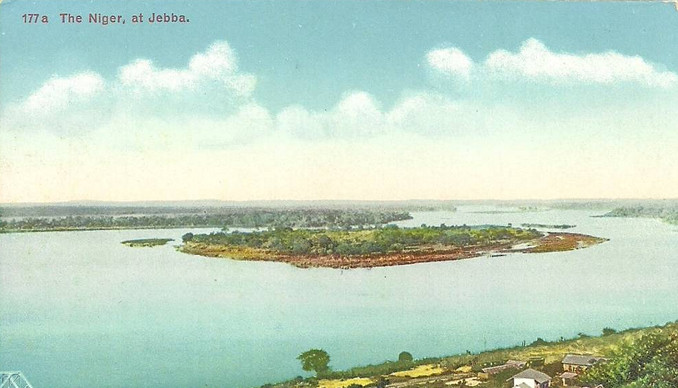

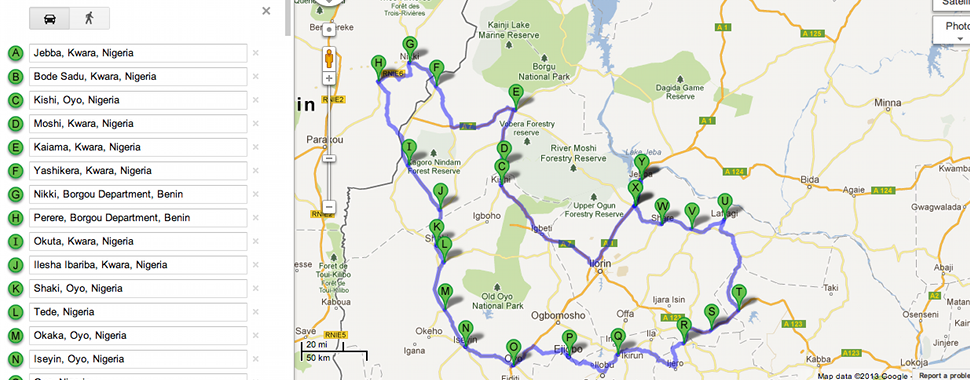

Lugard will go on to make a successful career as a colonial bureaucrat. In about three years, he will found the West African Frontier Force and later become the legendary inventor of indirect rule, the Governor of Hongkong, and the Governor-General of Nigeria. But at this point, he is just a young captain trying to hustle for some cash and something to hold on to after a failed career in the army and bad romance. After India, he worked for a British trading company in East Africa, but following a scandal that involved mistreating French missionaries and Africans, he lost his job. When we meet him in the spring of 1894, he is pretty down and out. But he soon gets a break when the Royal Niger Company commissions him to go on a 700 km expedition from the mouth of the island of Jebba on the Niger River to Borgu, a disputed territory in the northwest border of what is now Nigeria and Benin Republic. The image below is an approximate map of Lugad’s journey.

Lugard arrived in Jebba on Sept. 8. In about a month, he put together a caravan consisting of 342 Africans, 3 Europeans, 50 donkeys and 6 horses. 336 of these Africans were porters, each carrying an 80-pound load on their head. The loads contained food and camping gears for the Europeans, cheap ammunitions—mainly snider rifles and bullets—, expensive fabrics for gifts to African chiefs and cheaper ones to barter for food. This multitude of men and beasts of burden formed a caravan that was 1 and 1/2 mile long. They walked an average of 10 km daily for nearly three months. Can you imagine trekking through forest terrain in blazing hot days, heavy rain, dense fog, a rotten and feverish body, under threats of being attacked by marauding bands—can you imagine doing all that with such a large company of men most of whom spoke different languages?

This was late 19th century, so we already have the days of explorer-expeditions behind us. Lugard was no Mungo Park neither was he a Stanley. He was not on some romantic journey through the dark continent in search of the source of some river. He was on the payroll of the Royal Niger Company, a chartered company caught up in a bitter dispute between Britain and France over a territory on African soil. Lugard was on an expressly political and commercial mission. He had been sent to sign a treaty with the king of Nikki, the assumed capital of Borgu.

Lies and Intrigue.

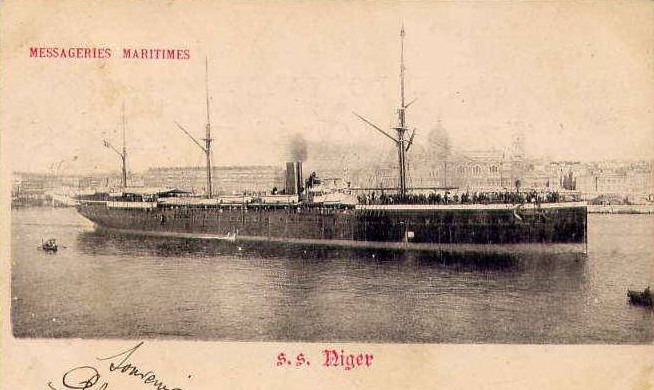

Lugard and the Royal Niger Company were not the only ones on the trail of this treaty. Four days before Lugard left Liverpool on a ship called S.S. Niger, Captain Decoeur of the French colonial army left Marseille. The Lagos-Badagry border up to Latitude 9 north was their common destination and the acquisition of the Nikki Treaty their common objective. To tell the truth, getting the treaty did not guarantee either side the acquisition of the territory. At best, it gave them bargaining power. A treaty had very little legal value since African kings were not really considered legal subjects under European international law. Signing a treaty with an African king simply meant that in the event of a dispute whoever had a treaty had a slightly better case than the party without one. Nevertheless, France and England thought that a treaty with the King of Nikki will help their cases in the on-going diplomatic talks between Paris and London.

Lugard was the first to arrive in Nikki, on November 5. By the 10th, he had signed the much coveted treaty. Given the sensitive nature of the document, he mailed it off the following day. But there was a slight problem…perhaps not too slight since it ended up preventing the British from making any conclusive claims to the region.

Soon after Lugard arrived in Nikki, he got acquainted with this man who claimed to be the right hand man of the King. Lugard held several private meetings with him, mostly at night. During their first meeting, this man, who Lugard keeps referring to as “the Liman,” told him that the king had a superstitious fear of white people and so could not meet with Lugard. Here is how Lugard assessed the situation in his diary:

The Liman is an old man, somewhat garrulous but shrewd. I found out from him that the real obstacle is that the King—or rather the people—are possessed by this prophecy that if the King sees a European he will die within 3 months. He said that nothing will induce them to allow me see the King.

Lugard did not suspect any foul play. He believed the fellow even when he told Lugard that since the king wouldn’t be able to sign the treaty, he would gather together a group of chiefs who would act as proxy. The signing was done in secrecy—at night. Lugard was quite happy that he had beat Decoeur to the chase. He generously paid “the Liman” and his group of chiefs both in cash and expensive fabric and happily continued his journey.

About two weeks later, Captain Decoeur got to Nikki with 145 soldiers and signed his own treaty with the King. In the course of the dispute with England, which dragged on for another three years, France claimed that Lugard’s treaty was fake. He had been duped by the King’s lackeys. How could Lugard sign a treaty with a King he did not meet face to face? Decoeur, who apparently met the King, also claimed that he was certainly not blind, as Lugard claimed. Really, it doesn’t take much to dupe a man like Lugard, who believes that just because he gads about about rain forests in Kaki shorts he knows everything there is to know about Africa and Africans.

It gets worse. The name of the King that appeared on Lugard’s document was not even the King’s name. Lugard did realize this before he mailed the documents and tried to doctor the documents accordingly, only for him to change the wrong name for another wrong name. Don’t be too surprised. Touching up treaties or outrightly forging them was a pretty common thing during the early years of annexation.

For three years, the dispute dragged on. In all this, there was no rest for Lugard. He kept writing “long memoranda indignantly defending his treaty and good faith.” We know it was wasted effort because in the intervening years negotiations broke down, France and England came awfully close to the brink of war in West African soil and even when diplomatic agreements were finally reached, France got the far larger share of Borgu.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions