Last fall, Joel Cabrita contacted me, reaching out to send an advance copy for review. Interestingly enough, it was the semester when I was teaching my African Feminisms writing course, and a couple of weeks earlier, I had shared with my students the significance of granting a woman from the past an archival presence, which I argued was a truly powerful and life-giving feminist gesture. Women lead captivating lives filled with remarkable experiences. However, the unfortunate reality is that once they pass away, their stories often disappear, leaving future generations oblivious to their achievements. These absences accumulate over time, resulting in profound silences that eventually transform into complete erasures. Even before I read it, I understood the importance of a book that challenged this culture of forgetting by centering the life of an African woman. Having read the book, I find myself deeply moved by the story of Regina Twala—a scholar, politician, and educator from Eswatini—and the burning ambition that fueled her extraordinary life.

Regina Twala, who was born in 1908 and died in 1968, witnessed pivotal moments in southern African history, from the rise of apartheid in South Africa to the establishment of the ANC. She was part of a trailblazing generation of African women who counted among the first of a new professional class. Twala was exceptional by any standard. She led a public life and made outstanding contributions to intellectual communities both in South Africa and Eswatini. Yet, she died in relative obscurity and has remained so for many decades.

How could a woman who ran for public office, was the second black woman to graduate from the University of Witwatersrand, wrote numerous scholarly articles, built a community library, wrote six books, was married to a fairly known figure in the South African theater scene, co-founded a political party, and was friends with the Mandelas be entirely forgotten in accounts of 20th-century African intellectual life? How is it that a woman who left behind so many traces of her impact on the world could have become untraceable?

Puzzled by Twala’s inexplicable invisibility in 20th-century African intellectual history, Cabrita sets about writing this compelling story of her life. She talks about how, at the beginning of her investigation, she would call up historians, political activists, and journalists and ask, “Have you heard of someone called R. D. Twala, who ran as a candidate in the 1963 legislative election in Eswatini?” and would consistently receive a negative response. She couldn’t shake off the “ongoing public amnesia” about “a woman as talented, unusual, memorable, and prolific as Regina Twala.” Read our interview with Cabrita about her book here.

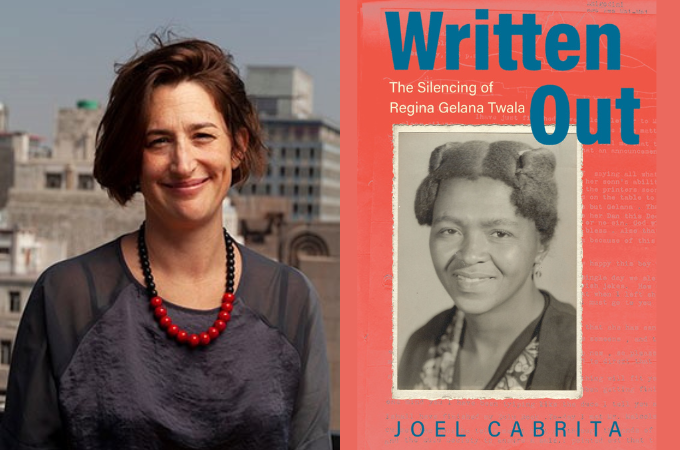

In the essay “To Be An African Woman Writer,” the late Prof. Ama Ata Aidoo reminds us that women are forgotten not because they achieve too little but in spite of their overwhelming public accomplishments. She was referring to the politics of exclusion that plague a publishing industry and literary culture that still give men and their work more visibility. Cabrita cites Zukiswa Wanner’s comment about “black women’s ‘flirtation with erasure,'” remarking that it captures the lack of representation of African women in various life writing genres. Koleka Putuma addresses a similar issue in her recent poetry collection “Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come In,” about the systematic erasure of black, queer African women in the sphere of art and literature. With this book, Cabrita contributes to this ongoing discourse around the need to expose the culture and systems of erasure that write women out while doing the work of writing the lives of women into the present. “Written Out: The Silencing of Regina Gelana Twala” by Joel Cabrita is an intriguing work of historical investigation that seeks to share her life with readers who would find such a legacy inspiring and illuminating.

Cabrita does what is expected of a committed biographer. She tells Twala’s life story in a compelling narrative woven from a rich archive of details drawn from interviews with relatives, a captivating and extensive collection of nearly 1,000 letters, as well as official sources. She deftly layers the personal and political dimensions of Twala’s life in ways that make for a deeply moving and captivating read. I initially expected a typical scholarly book due to the fact that Cabrita is a professor of African history at Stanford University, so I was pleasantly surprised to discover that “Written Out” is an enthralling read, brimming with captivating details, gripping drama, and a respectful portrayal of Twala’s life. Cabrita masterfully captures the emotional truth of Twala’s experiences, transporting readers to mid-century South Africa where they witness both the larger societal forces shaping her life and her personal struggles, triumphs, and sacrifices. But she goes a step further. She brings Twala’s history to light within the context of her erasure, addressing the archival blind spots that produce these kinds of omissions in the first place. “Written Out” is not just a biography. It is a feminist anthem against erasure. In telling Twala’s story, Cabrita lays bare the underlying forces of racism and sexism that conspire to silence black women in history.

When people go missing in history, it is often women and other marginalized people, and it is not because they did not do great things. History is a system of facts, figures, and true stories, but it is also a circus of bias, blind spots, and exclusionary politics. Cabrita has shown us how to push through the erasures to give a woman’s world the visibility it deserves.

***

Buy Written Out: Amazon | Ohio University Press | Wits University Press

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions