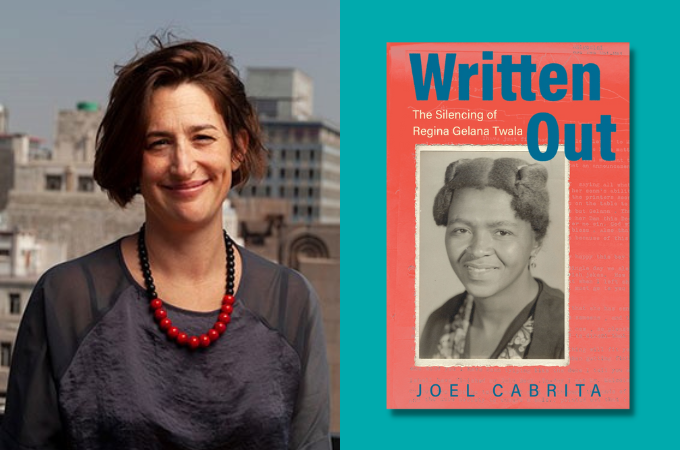

Joel Cabrita recently published a scholarly book titled Written Out: The Silencing of Regina Gelana Twala on January 17. The book explores the life of Regina Gelana Twala, a Black South African woman, who lived in the early twentieth century in apartheid South Africa and colonial Eswatini. Even though she achieved considerable success in academia and politics, her name is largely unknown, her literary achievements are forgotten, her books are unpublished, her articles are buried in discontinued publications. How was Twala written out of southern African history? Cabrita shows that Twala’s posthumous obscurity is no accident, charting how scholars and politicians used racial and gendered prejudices to erase Twala’s legacy and claim her intellectual labor for themselves.

In this interview, Cabrita talks about the book, the experience of writing, and reflects on various aspects of Twala’s life.

***

Brittle Paper

Can you tell us a bit about Twala, eSwatini, and the historical moment that you wanted to capture in the book?

Joel Cabrita

Twala was born in 1908 and she died in 1968, at the tragically early age of 60. When I first started researching her life, I was struck by the way in which her 60 years on earth encompassed many life-changing moments and events in African and world history. 1903, the war of Twala’s birth, was the end of the Zulu Rebellion, one of the largest Black armed uprisings against white colonial power. So this tells us that Twala was born into a century of great repression but also of political protest. 1913, when Twala was just five, saw the passing of the draconian Native Lands Act that disposed Black South Africans of their land by allocating the majority of the country to the small white minority. Twala’s own family – part of the rural elite of the country – were profoundly impacted by this. In the 1920s and 1930s, the spread of racist and sexist legislation made it incredibly hard for Black South Africans – especially Black women – to live in cities. Twala’s own move to the city of Johannesburg in the 1930s, and all the huge challenges she faced in doing so, needs to be viewed in this context. 1948 of course was the coming to power of the infamous apartheid government, a shift that had momentous consequences for Twala’s political as well as personal life. The rise of the apartheid government spurred on Twala’s political awakening, leading her to join the ANC and ultimately be arrested for her role in the 1952 Defiance Campaign. But the repressive political environment also led to the demise of her second marriage, to Dan Twala, as Dan was very opposed to a politically active wife. Twala’s growing political insecurity in South Africa, combined with the breakdown of her marriage, led her to relocate to neighboring Eswatini, where she spent the last 15 years of her life. And Eswatini was itself going through a tumultuous period in the 1950s and 1960s. Long a “protectorate” of the British, lively conversations were now happening about independence from Britain and multiple Black-led political parties were sprouting up, literally overnight. Twala was at the very center of these debates. Sadly, she died in August 1968, just one month before Eswatini finally gained its independence from Britain.

Brittle Paper

How was Twala “written out” of history and how does the book address that?

Joel Cabrita

My book argues that being “written out” of history is not accidental nor just due to the passage of time. Rather, erasure is a deliberate purposive act. It requires active labor to write people out of history. In the course of my research, I discovered there were three main groups of individuals who were responsible for writing Regina Twala out of history. First, there were the literary gatekeepers of colonial South Africa, including missionary-run presses and the department of education that functioned as one of the main publishers for Black writers of the day (their books were assigned as school readers). Both mission presses and the government vetoed Twala’s books, probably because they were considered too politically radical. There was also the small clique of her Black writer contemporaries, almost all of whom were male and espoused sexist attitudes towards women writers. Second, a network of European academics also conspired to write Twala out of history, including her former anthropology teacher and mentor, Hilda Kuper, who blocked the publication of Twala’s final MS thesis, motivated – I hypothesize – by territorialism and jealousy. There was also the Swedish historian, Bengt Sundkler, for whom Twala worked as a research assistant in the 1950s, who plagiarized Twala’s work. Finally, in the context of Eswatini, Twala’s anti-monarchy politics (she opposed the traditional monarch Sobhuza II as well as British rule) meant that after her death in 1968, the repressive Eswatini government ensured that her name disappeared from public memory. Telling Twala’s story means identifying and naming all of these active agents of her erasure.

Brittle Paper

What was the spark for the story? There are many African women in similar circumstances whose story you could have told. Why Twala?

Joel Cabrita

I was doing research in Bengt Sundkler’s archives at Uppsala University in Sweden, where he taught for much of his career. I was looking through his research materials relating to his work on religion in Eswatini, and I came across pages of notes and reports sent to him from one R. Twala, living in Eswatini. There was no other clue as to Twala’s identity – including whether this was a woman or a man – but I was immediately struck by the articulate and highly nuanced tone of their writing, plus the fact that this was clearly someone who was a trained anthropologist. I was determined to try find out more about this intriguing figure – all the more intriguing because they seemed to be completely unknown, no one could tell me anything when I asked in Eswatini about an anthropologist of the 1950s called “R.Twala”.

Brittle Paper

Regina was a writer in many ways, but I am intrigued by her aspiration to become a fiction writer. Tell us about that dream and what it says about her exceptional journey.

Joel Cabrita

What I notice with Twala’s literary career is that genres seem to blend and meld into each other in creative ways. So the distinction between “fiction” versus “non-fiction” doesn’t really hold for her. As you mentioned, she loved writing fiction, and in fact her first book – now sadly lost to us – was a novel that followed the adventures of her hero, Kufa, as he moved to Johannesburg to work on the gold mines. But even though she didn’t find success as a published fiction writer, Twala transferred some of that creative energy to her journalistic and ethnographic writings. Her newspaper columns are highly innovative, experimenting with mood, tone, narrative perspective, and pacing. Her ethnography, too, was sometimes presented in a fictional mode, in the format of stories she overheard. I sense she must have taken many liberties in how she reconstructed these conversations, enjoying creative license. So a writer like Twala seems to defy genre. In part, this was a product of the difficulties she found in being published. Paradoxically, lack of formal publication meant that Twala wasn’t confined to a single literary “box” but could nimbly move across, between, and within genres.

Brittle Paper

You present Twala through such lifelike images. I feel like I have a sense of who she was, what inspired her, her frustrations with her circumstance, her bold and powerful aspirations, etc. What was it like re-imagining not just her experience but also her voice, action, and gestures?

Joel Cabrita

One of the decisions I had to take as I wrote this book was whether I was going to dare to imaginatively recreate aspects of Twala’s life that I had no or little access to. So you’re right that my book takes what some readers might consider the liberty of imagining at certain moments what Twala was feeling or thinking. These are moments for which I cannot point to historical source material to fully back me up. This is certainly a decision that not all historians would take. But I felt that in this case it was important because I wanted this to be as vivid and life-like an account of Twala as I could create, showing her in all her entirety – not just as a political public figure but also as a woman, lover, a wife, a mother, a devout Christian believer. I was helped by the fact that Twala left behind an extraordinarily personal and intimate archive in the form of her 30-year long correspondence with her husband, Dan. Through these letters I gained insight into Twala’s emotions, her sexual desires, and her insecurities – aspects of a self that a more official public archive doesn’t usually reveal. There were also the dozens of photographs of Twala throughout her lifetime. These black and white images – themselves an important archive of Black middle-class life during the apartheid decades – provided me with striking visual cues that I heavily drew from in writing her biography. Poring over the photographs, I discovered important clues as to her fashion choices, her facial expressions, and her bodily gestures and posture. The photographs helped me feel as if I truly knew her.

Brittle Paper

Tell us about the research that went into the book. Did you go to archives? Did you talk to a lot of people? Were there challenges along the way?

Joel Cabrita

One of my most significant sources for writing Twala’s life was the phenomenal collection of letters she left behind after her death. There are nearly 1,000 letters largely exchanged between her and her second husband, Dan Twala (an important figure worthy of a biography in his own right – he headed up the Bantu Sports Club for decades, a key leisure institution in twentieth-century Johannesburg). These letters are now deposited with Wits Historical Papers (Wits was Twala’s alma mater) and are in the process of being digitized so future scholars can delve into them. But when I first came across the letters in 2018, they were kept in the private Johannesburg home of South African historian, Tim Couzens. Couzens had interviewed Dan Twala in the 1970s (interestingly, his focus was on Dan, not on Regina), and Dan had lent or given Couzens the letters to use in his research. For whatever reason, Couzens never wrote anything on either Twala, and even after his sudden death a few years ago, the letters were still kept in his personal home study. For me this raises important questions about archives, private collections, access, and ethics – when I first consulted the letters in 2018, Twala’s own descendants had no idea about their existence, something that seems fraught given the highly personal nature of their grandmother’s correspondence. And speaking of family, Twala’s descendants were of course my first port of call in terms of people to interview. The support and generosity of the Twala family has been absolutely foundational to my biography. And in a context where many people simply don’t remember Twala (combined with the fact that her contemporaries and peers are passing away due to advanced age), family members’ memories and preservation of materials linked to Twala’s life have been doubly important to me.

Brittle Paper

How did your sense of Twala’s life shift through the course of the research?

Joel Cabrita

That’s an interesting question for me. I feel there has actually been a notable consistency in my sense of Twala throughout this project. My initial hunch was that she was an important unknown intellectual, and that conviction only strengthened as I discovered more and more about her life. My biggest surprise, however, was realising just how formidable all her opponents were – from jealous academics to censorious publishers to conservative male politicians. At the start of this project, I hadn’t quite appreciated the enormous range of obstacles Twala had to negotiate throughout her life. As her biographer, I definitely became more empathetic to Twala’s struggles the more I found out about her.

Brittle Paper

At the heart of this book is an epic love story between Twala and her husband Dan. When and how in the research process did you discover this aspect of her life?

Joel Cabrita

As soon as I discovered Regina and Dan’s letters to each other, I realize that this truly was an epic love story, one of the greats of African history that deserves to be up there with Nelson and Winnie Mandela, Seretse Khama and Ruth Williams, and so on. The letters chronicle their intense physical attraction to each other but also give insight into the relationship as a true meeting of two minds. They loved talking to each other about just about every topic imaginable. But as I worked my way through their huge correspondence, I realized that the love story did not have a happy ending. As the decades went on, Twala and Dan actually fell out of love with each other, driven apart by their clashing views on politics and Dan’s opposition to a woman’s career outside of the home. One of the saddest aspects of her life, I find, is the way in which the couple gradually grew more and more disillusioned and bitter with each other. From being her greatest cheerleader, Dan became a serious thorn in Twala’s side. So this is both a love story as well as a story of how a once close couple fall out of love with each other. Of course, Dan’s infidelity didn’t help matters. My book describes how Twala was so enraged at finding out he’d fathered a child with another woman that she threw a pot of boiling water into Dan’s face . . . A far cry from her utter besottedness during the early days of their courtship.

Brittle Paper

There are many facets to Twala’s personality. How did you balance the need to represent her greatness as a figure of politics and culture and show her personal, intimate self?

Joel Cabrita

One of the ways to think about this issue is through a feminist lens. Twala’s public career – her political work, her literary achievements, her contributions as a social worker in both South Africa and Eswatini – can’t be understood in isolation from the personal struggles she was undergoing as a Black woman of the twentieth century. Her political commitment to Black liberation was shaped by her own intimate experiences of discrimination, prejudice, and deeply unfair treatment (for example, my book tells how Twala, one of the most educated women in South Africa of the 1930s, was compelled to work as a domestic worker in a white household for a period). And Twala’s lifelong conviction that Black liberation had to be built upon a bedrock of female emancipation was informed by her own experiences of being knocked back time and again by the men in her life. Two unfaithful husbands greatly influenced Twala’s political commitment to female autonomy. In this sense, the personal was the political. There’s no extricating Twala’s public persona from her intimate self.

Brittle Paper

You are a white historian telling the story of a Black African woman, which some might see as fraught. Is that something that you thought about as you worked on the book?

Joel Cabrita

This is something I’ve thought about quite extensively, at all stages of the project. In fact, an earlier draft of the book had much more explicit reflection on my own positionality as a white Northern hemisphere-based researcher, and what this meant for my telling of Twala’s story. But in the published version of the biography, I decided to cut back on this. The world doesn’t need more stories of white angst. Thus, I felt that I should keep the focus firmly on Twala’s life and career, rather than on my own ponderings about myself. But nonetheless, it’s an important facet of this story. I think it’s a great sadness that Twala has only come to public attention through the intervention of a white scholar, and I think that this speaks volumes to the continued persistence of white privilege. I also notice the irony that Twala’s lifelong marginalization at the hands of white academics has culminated in a white academic writing her biography. Biography is an ambiguous process; it both highlights the biographical subject as well as gives prominence to the biographer herself. So there’s an often uncomfortable power dynamic that threads through the heart of the biographical enterprise. I strongly feel the ultimate goal is for Twala’s own work to finally find a publisher. Rather than being mediated through my telling of her life, Twala deserves a platform to finally speak to the world in her own right and to tell her story in her own terms.

Brittle Paper

The book does not sound like a conventional academic text. I mean it as the utmost compliment. It reads like a biography, with beautiful narrative pacing, vivid details, and character exploration. Would you say that is your typical writing style or was it a deliberate choice with this particular book?

Joel Cabrita

Thank you! I definitely take that as a compliment, and it’s something I tried to aim for. My previous books have been written in a much more conventional academic style. I felt that a biography demanded a different kind of approach, and I was eager to experiment with that. I’ve long found it puzzling how we academics don’t think much about the craft of writing (beyond clear exposition and argument). Words tend to be treated as a vehicle for our ideas, rather than something significant in their own right. I’ve found that biographical writing has freed me to engage more with the “wordiness” of the writing process, considering factors like pacing, character, plot, description, etc. I’ve really enjoyed that and I think I’ll find it hard to go back to more conventional academic writing after this . . .

Brittle Paper

Let’s talk about communication technology and how it shapes experience. Letters play a huge role in the world of the book. Tell us more about Twala’s letters and her attitude towards letter writing?

Joel Cabrita

Writing this book has convinced me that letters can be a serious literary genre in their own right. Letters have long suffered from not being taken seriously by scholars as “literature” (something compounded by the fact that they’re often linked with women, the home, domestic pursuits and interests; the perception that in the past men published books, women wrote letters). But Twala’s letters tell us a very different story. They’re radical and experimental; they play around with perspective, with voice, with satire, with irony, and with addressivity. There are letters in which Twala adopts an entirely different persona, writing to her husband, Dan, as a man, for example. Letters were not just the precursor to Twala’s actual writing; they were her writing. I’d love for a collection of them to be published one day. And Twala herself had a sense of her letters as “literary”. In my biography, I describe how she would often separate out sensitive material, writing it on a separate page for Dan to destroy after reading. Her motive? She was convinced that her letters would have an audience in years to come and so she was engaged in the work of editing and shaping them for future readers even as she was writing them. I love how this subverts our typical understanding of letters as private. Twala wrote both for her husband, Dan, and for readers like you and me, decades later.

Brittle Paper

Why now? Why do we need Twala’s story in our current climate?

Joel Cabrita

My book makes the point that many of the forces that repressed Twala during her lifetime are still, sadly, active today. Eswatini is still very much in the grip of an oppressive monarchy. If anything, it’s far more repressive than it was during Twala’s lifetime. The flowering of democratic activity in the 1960s (with many different political parties emerging, for example) is completely lost. Political groups have been banned since the early 1970s. Twala’s world of political debate, voting, and outspoken journalism is a thing of the past. There is now no free press in Eswatini. And more broadly, as many activists and scholars continue to show us, racism and sexism are alive and well in the academy, in the publishing world, and in politics. So Twala’s story of being written out of memory, out of history, and out of her legacy is one that still continues to play out in multiple contexts around the world today. I wish that this was a story of a long-gone era that we can safely shut the door on. Sadly, there are still many women who are finding themselves being similarly written out of history, even today. Twala’s story reminds us to not forget those present-day women. Hopefully, it also reminds us that we need to continue to hold repressive forces accountable, whatever shape and form they take.

Brittle Paper

Thank you for speaking with us about your book, Joel.

***

Buy Written Out: The Silencing of Regina Gelana Twala by Joel Cabrita: Amazon | Ohio University Press | Wits University Press

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions