[Adichie] is the sort of writer who would notice the advertisement of a plumber scrawled on a wall, piles of rubbish rising by “the roadside like a taunt” and how in London “night came too soon, it hung in the morning air like a threat, and then in the afternoon a blue-grey dusk descended. . .” — R. Ali

By Richard Ali

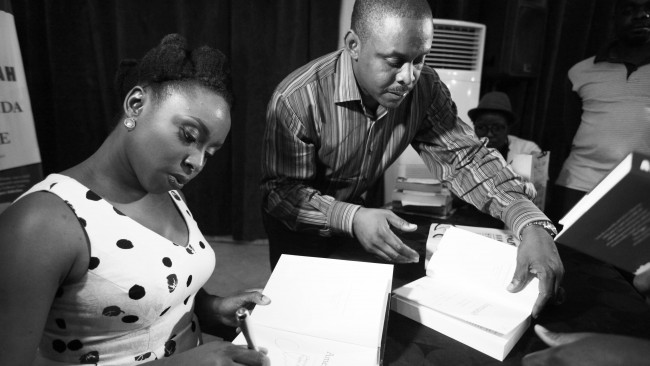

As a critical reader caught up in the mood of new African writing since 2001—using Helon Habila’s Caine Prize win as a rough marker—I’ve taken an interest in the writings of that delightful crop of now ageing writers. Perhaps the most popular of these is a female voice, Chimamanda Adichie’s, whose debut novel, Purple Hibiscus, I read and loved as an undergraduate. Chimamanda Adichie has a new novel out, her third, Americanah (2013) published in Nigeria by Farafina Press.

Americanah is a meditation on uprootment and displacement tagged unto the sinews of a love story. It is the love story of Ifemelu and Obinze, adolescent sweethearts who become estranged and then meet up thirteen years and a world of experiences later—a basic love story plot. But their estrangement is not the sort borne in conscious choice when love is done and lovers cannot be put up with any longer, nor is it the classic one arising from the designs of villains to keep lovers apart. Theirs is an estrangement born out of a need for internal mental exile, for while it is true that Ifemelu leaves for the United States and Obinze heads to Britain from where he is deported, the suspension of their affair comes from the change Ifemelu sees in herself on arrival in America. In the shock of her arrival, perhaps captured in her summation of the Manhattan that America-smitten Obinze dreams of, one that is “wonderful but not heaven”, she withdraws into herself and Obinze is forced to follow in the wake of her silence. The suspension of their affair runs in the period of Ifemelu’s education, in which America educates her such that she gathers her nuances and becomes full fledged person, becomes mature, making the novel a coming-of-age story similar to Chimamanda Adichie’s debut novel. And it is precisely this scrutiny, this keen observation of the social fabric of America and Nigeria and how they inform the life choices of Ifemelu, that Adichie acquits herself of having let off on the promise of Purple Hibiscus in her subsequent books.

Told in fifty five chapters over the course of seven “parts”, the first thing apparent in this novel is the experimentation with form. The most explanatory bits, the ones that put a thermometer to Ifemelu’s life, come in the form of posts taken from her blog—an epistolary device presenting a back story without which the main plot would have been irredeemable trite. This willingness to experiment with form was noticeable in Ms. Adichie’s second novel, Half of a Yellow Sun, where the device of the parallel feeder story of Ugwu fails completely. In a reversal, in Americanah, this device succeeds by its being organic to the story being told, and not, in the case of Half of a Yellow Sun, relying on the extra-literary context of a historical civil war to make the creative fiction work.

Race and identity form the most part of the American education of Ifemelu and grounding the centrality of race and identity, most of the novel is set in a Senegalese hair salon in Trenton to which Ifemelu, now a successful and well paid blogger, comes down from her fellowship at Princeton. A large chunk of the story is thus told in flashbacks—Ifemelu’s childhood, Obinze, America and her love affairs, even her blog—for at the time the story proper starts, with she sitting to have her hair braided by Aisha, she is set already to return to Nigeria after thirteen years in America. These flashbacks, or dips into memory, are effectively handled by Adichie such that there is no sense that the story has been suspended—her digressions build up the story and the character of Ifemelu. It is subtly done but these flashbacks are a stripping off of Ifemelu’s naiveté so we come to see the flawed maturity she returns to Nigeria with—one flawed by the impact of race in America. Concerning race, she becomes headstrong as a sort of overcompensation. On discovering in America that she is “considered black”, Ifemelu decides to create for herself a self-referential Blackism. Her blog, “Raceteenth, or Various Observations About American Blacks (those Formerly Known As Negroes) By A Non-American Black” is a chronicle of this Blackism. But the novel is not just about race. On the contrary, it is about something larger of which race is only a part. Ifemelu’s decision to close the blog and return to Nigeria is a realization of this larger syndrome. She closes her blog when she becomes disillusioned with its appeasement of mere symptoms.

Americanah is largely the story of Ifemelu, but there is also her love-interest, Obinze. Obinze highlights the problems of the innovative point of view Ms. Adichie employs in this book for while her use of flashbacks and the epistolary device for Ifemelu makes her a well rounded character through whose eyes we can empathize with Aunty Uju and her son, even with Blaine and Curt her lovers, with Kimberly and her bitter sister and the sports coach who sexually humiliates her, there is no such touch in the portrayal of Obinze. We see him first through Ifemelu’s eyes, and for the most part he is reacting to her moves. He only shows up as a character of some substance in Part 3 of the book where 57 pages are dedicated to his experience as an illegal immigrant in London—from arrival to deportation. Important as this experience is, we fail to see how this becomes definitive in Obinze’s life. His angst on being deported from the United Kingdom comes across as petulant, and we cannot even see this as a reaction to rejection by “the West” for the United Kingdom is not by any stretch equable to the America of his ideals. And perhaps this is it, the lack of concrete ideals? Beyond a childish veneration of America and his apparent sexual skills as far as Ifemelu is concerned, there is little else about Obinze. All we see about his life in England—life without papers, changes of identity, an attempted arranged marriage—are the run of the mill things already known in detail from decades of stories of illegal immigrants. Consequently, when he becomes a member of the Nigerian nouveau riche, we are unsure what is lost. When he makes the fatal decision concerning his wife and child, we are unsure of what the human incidence of this is. Obinze’s lack of realization is a weakness of Americanah, a weakness redeemed by Ms. Adichie’s prose and style, but a weakness nonetheless.

There is always a core to every story and the delicious task for the literary reader is to seek this out. With some writers, it is easy enough—often the core is so related to the theme as to be indistinguishable from it. Ms. Adichie, in this novel, makes what her novel is about a more intriguing exercise. Is it simply a love story? There are Obinze and Ifemelu. Is it a meditation on race? There is the screedy yet perceptive blog. Is it a feminist liberationist piece of agenda writing? There is Aunty Uju and the parallels in Ifemelu’s life. Is it a coming-of-age story? In part but not quite. The central thing that runs through the novel is definition and the ideas associated with it. Ifemelu, who is the central character, comes across this from the very first pages, in her neurotic mother’s finicky changes of religion and its underlying hypocrisy—with each new church, she has to be a certain sort of ideal person. Womanhood, the social construction around feminity, comes via Obinze and his academic mother, who is an advocate of “protection”, who asks to be told when Ifemelu and her son have sex. Definition as commodification, as a being that can be kept is experienced firsthand in the life of Aunty Uju and the General for whom she is a kept woman. At some point, Ifemelu becomes “Curt’s Girlfriend”—a “role” she “slips into”. In America, Ifemelu becomes Black, the first of the definitions she reacts against by creating a blog-based blackism of the Non-American Black variety. Significant to finding the core of this novel is Ifemelu’s closing her blog and returning to Nigeria. Yet, even in Nigeria, she is sought out to become an “Americanah”—a disconnected and parasitic ex-Diasporan not much different from the “Bartholomew” character in the book still stuck in the West.

But at every point in time, there is heard the dissident voice of Ifemelu. When her mother ascribes to God’s benevolence Aunty Uju’s being able to afford a new apartment in a posh part of town, Ifemelu says “Mummy, but you know Aunty Uju is not paying one kobo to live there.” The house was of course paid for by Uju’s lover with whom, in the books of her mother’s religion, Uju is fornicating with. On reaching America and encountering the famed American sense of humour, she does not merely memorize its punch lines, she wonders—“How did they know when to laugh, what to laugh about?” When a poet sunnily says Obama’s win will end racism and that race was never an issue in her three year relationship with a white male, Ifemelu replies “That’s a lie.” She wonders at a point why Curt, her white lover, can see some things regarding race clearly but still be incapable of taking the next logical steps that perforce arise from this clarity. The core of the novel is the idea that people should not be pigeonholed into any categories at all and that being in a state of flux is a good thing, that it is perhaps the natural state for the emancipated, liberated person. Further to this, that when a person, beyond liberation and emancipation, chooses a label, it should be respected by others for so long as such choosers identify with it which, of course, lasts for so long as they are comfortable with it. Naturally, this leads to a chaos. But is not Ms. Adichie’s meaning that the effects of this idea would be less chaotic, have less wreckage along the way [Curt, Blaine, Obinze’s wife and daughter], if it was held for everyone and not just for mavericks like Ifemelu? Thus, the novel, Americanah, apart from being well written, pushes the boundaries by introducing a new social idea—of an equality that is scrupulously humanist, with an allowance for an inalienable choice in the assertion of how exactly one wishes to be identified and interpreted.

Admirable in this book is Ms. Adichie’s eye for detail, extremely perceptive and aware of what is consequential both in terms of plot and character. She is the sort of writer who would notice the advertisement of a plumber scrawled on a wall, piles of rubbish rising by “the roadside like a taunt” and how in London “night came too soon, it hung in the morning air like a threat, and then in the afternoon a blue-grey dusk descended. . .” Without the long walk by the beach that is the length of this book, without the excited child coming in with a new treasure of sea detail for a keepsake, this novel would have been unreadable. A gem of perception is this one on the misogynist character Bartholomew who is representative of the Diaspora Nigerian—

“He had not been back in Nigeria in years and perhaps he needed the consolation of those online groups, where small observations flared and blazed into attacks, personal insults flung back and forth. . . Afterwards they would return to America to fight on the internet over their mythologies of home, because home was now a blurred place between here and there, and at least online they could ignore the awareness of how inconsequential they had become.” Pg 117.

and

“I imagine myself as an outsider saying: Go back where you came from! If your cook cannot make the perfect panini, it is not because he is stupid. It is because Nigeria is not a nation of sandwich-eating people and his last oga did not eat bread in the afternoon.” Pg 421.

These perceptions sear through the core of sociology and personality in a way that a less skilful writer would seek to express in paragraphs of pretty prose and still fail to get across. This eye for significant detail and the deft touch with which Ms. Adichie presents her details is what stands her out as a writer. It also makes Americanah a pleasure to read. A final example of this would suffice to end this review, it comes up very early on in the book—at about the time Ifemelu and Obinze fall in love after meeting at a party where he was to be hooked up with someone else, her friend Ginika. Ifemelu, in an adolescent insecurity, imagines “Obinze realizing how better suited Ginika was for him, and then this joy, this fragile, glimmering thing between them, would disappear.” Like the love between her two characters, Ms. Adichie pulls off a fragile, glimmering book with far more dexterity than they did in their tumultuous but ultimately redemptive love affair.

Image via

Thanks to Richard Ali for this insightful review. Ali is a Nigerian lawyer and the author of City of Memories [Parrésia, 2012]. He edits the Sentinel Nigeria Magazine and is Publicity Secretary [North] of the Association of Nigerian Authors. He lives and writes in Jos, Nigeria.

Thanks to Richard Ali for this insightful review. Ali is a Nigerian lawyer and the author of City of Memories [Parrésia, 2012]. He edits the Sentinel Nigeria Magazine and is Publicity Secretary [North] of the Association of Nigerian Authors. He lives and writes in Jos, Nigeria.

Follow him: @richardalijos

Ositadinma December 28, 2019 17:21

There is no core, sir. Stop looking for a core in a novel that even asks the question, why would anyone see a novel as one thing?