A long while back, Teju Cole tweeted, while he was in Lagos, that he had being robbed.

A long while back, Teju Cole tweeted, while he was in Lagos, that he had being robbed.

Granta has just published his account of the experience. You can find it in the recently issued Granta 124: Travel. The essay is titled “Water Has No Enemy”, clearly referencing Fela’s song titled “Water No Get Enemy.”

There are two excerpts of the essay available online, the one on being robbed at gunpoint and a short one on Bar Beach that I think is beautifully evocative of a peculiarly Nigerian urban experience.

Is this Granta piece in anyway connected to the book project on which he is working at the moment. Earlier in the year, Guardian UK hinted that Teju Cole might surprise us with a book in 2013, a non-fictional work on Lagos. Since then we’ve not really heard anything substantial about this work. Part of me is hoping that this essay is in anticipation of the book.

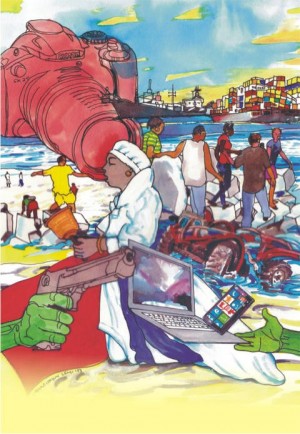

I am also in awe of the accompanying image to the essay. It’s a piece done by the legendary Lemi Ghariokwu, a Nigerian illustrator known for his work on Fela’s album covers. Lemi is fast become a Lagos institution. It only makes sense that Teju Cole pays homage to his work in his writing on Lagos.

A street trader taps on the window on the driver’s side. These boys are sometimes aggressive with their sales pitches, and we ignore this one. But he knocks more urgently and when I look up I see that he’s waving a pistol. My momentary confusion is not dispelled by his pointing at my computer. His face is contorted with rage, and he’s shouting. In the sealed interior of the jeep we can make out his words, ‘I will shoot you! Wind down. I will shoot you!’

Even after I realize that we are being robbed, that bullets can shatter glass, that being locked in is no help in this situation, I still feel a vague resentment at having to hand the laptop over. It’s mine. It contains my work, a week of writing, a month or more of photography, personal information. I have hesitated only a few seconds but feel as though I have just woken from a trance: briefly, I imagined myself with a bullet in my thigh, imagined myself bleeding out in traffic in Ojota. We turn the radio off and open the window. The gunman is small, thin-faced. We are surrounded by other cars but he doesn’t stop shouting, as though something in him, and not he himself, were pushing the voice out of his chest. I don’t even have the time to close my Facebook page or unplug the Internet modem. I close the laptop and hand it over to him. ‘Your phones, your phones! Give me your phones!’ Doyin hands his BlackBerry over. I have to dig in my bag for the Nokia handset I use when I’m in Nigeria, my hands shaking the entire time. The man doesn’t stop shouting. I’ve never had a loaded gun pointed at me before. Who is this man? What horrors of deprivation have pushed him to this extreme? His glare is so hard, so callous, that I am certain he doesn’t see us, that he sees only whatever it is he imagines we represent. — Read full excerpt here.

You know you’re an African writer if…. | siyandawrites.com June 11, 2015 15:30

[…] may not be as good as Teju Cole, nor as well-traveled as Lerato Mogoatlhe but I did let a nyaope-addict punch me in the face and […]