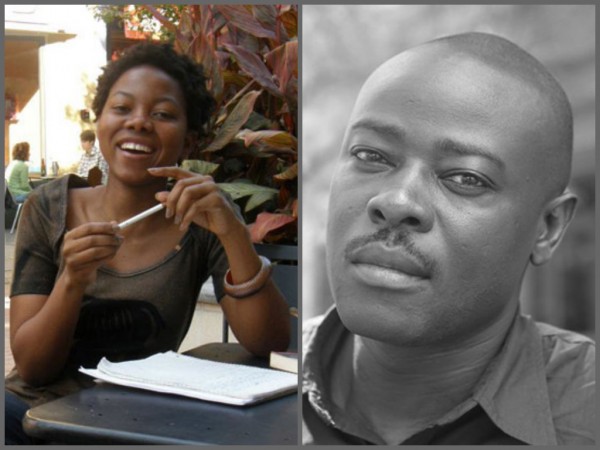

A few days ago, Zimbabwean author, Noviolet Bulawayo, writes on her Facebook wall:

Today I woke up to some South African love, and it’s very meaningful to me, for obvious reasons. I am remembering that my very first published story was by Munyori journal, and it meant a lot to have that Zim and African connection for my first published thing. Also, my first ever award experience was an honorable mention for the SA PEN-Studzinski Award, I think it was for Southern Africa at that time and then of course, right after, Caine, which, some of you may remember, also made me a poverty pornstar, a title that didn’t, and doesn’t, phase me. I don’t write for these things, of course, but still, I don’t take them lightly, and the recognitions that have connections to the continent remind me that I am not just a writer, but I also come from a specific place, and that matters a whole lot. ngiyabonga mina.

The story of how Bulawayo became a “poverty pornstar”—[Lol. can’t get over the term]—is actually not at all complicated.

Here it goes: Bulawayo’s debut novel, We Need New Names, was published on the 21st of May 2013. Exactly one month later, Nigerian novelist, Helon Habila, published his now famous review of the novel in the UK guardian. The review was generally negative. Habila writes that Bulawayo’s short story, “Hitting Budapest,” that won her the Caine Prize and that became the basis of her critically acclaimed debut novel is iconic of a certain kind of literary work that represents Africa as a space of suffering, wretchedness, and despair. She clearly read the review and was a bit miffed. But, she doesn’t seem to be bothered. As she puts it in the Facebook status: “poverty pornstar, a title that didn’t, and doesn’t, phase me.”

Habila may have popularized the term, “poverty porn,” but he may not have been the first to use it. I don’t know who coined it, but the Nigerian critic, Ikhide Ikheloa had used the term in a Brittle Paper interview a few months before.

In case you didn’t read Habila’s review, I’ve excerpted key paragraphs:

I was at a Caine prize seminar a few years back and the discussion was on the state of the new fiction coming out of Africa. One of the panellists, in passing, accused the new writers of “performing Africa” for the world. To perform Africa, the distinguished panellist explained, is to inundate one’s writing with images and symbols and allusions that evoke, to borrow a phrase from Aristotle, pity and fear, but not in a real tragic sense, more in a CNN, western-media-coverage-of-Africa, poverty-porn sense. We are talking child soldiers, genocide, child prostitution, female genital mutilation, political violence, police brutality, dictatorships, predatory preachers, dead bodies on the roadside. The result, for the reader, isn’t always catharsis, as Aristotle suggested, but its direct opposite: a sort of creeping horror that leads to a desensitisation to the reality being represented.

…

NoViolet Bulawayo‘s new novel, We Need New Names, is an extension of her Caine prize-winning short story, “Hitting Budapest“, and yes, it has fraudulent preachers and is partly set in a soul-crushing ghetto called Paradise, somewhere in Zimbabwe. Yes, there is a dead body hanging from a tree; there is Aids – the narrator’s father is dying of it; there is political violence (pro-Mugabe partisans attacking white folk and expelling them from their homes and chanting “Africa for Africans!”); there are street children – from the ranks of whom the narrator, Darling, finally emerges and escapes to America and a better life. Did I mention that one of the children, 10- or 12-year-old Chipo, is pregnant after being raped by her grandfather?

There is a palpable anxiety to cover every “African” topic; almost as if the writer had a checklist made from the morning’s news on Africa. There’s even a rather inexplicable chapter on how the Chinese are taking over Africa, and how, as one of the street kids puts it, the Chinese “are not even our friends”. Such moments are made possible by its rather free-ranging, episodic plot structure.

— Helon Habila, The Guardian. Read Full Review

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions